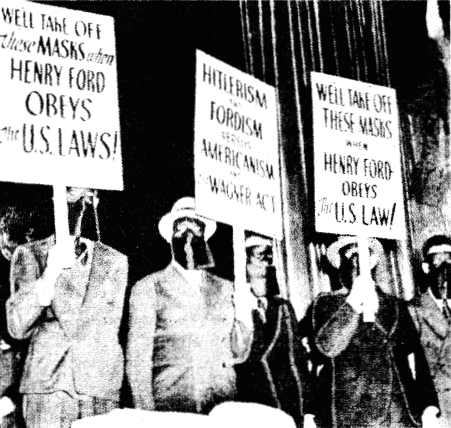

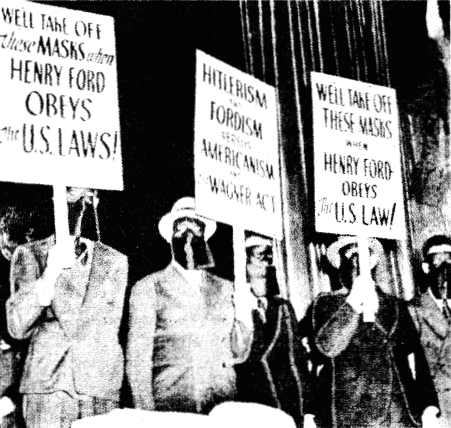

Ford workers at 1935 New Jersey CIO Convention, masked to avoid recognition by company spies.

It is a revealing comparison that during the 1930s the European imperialists could only resolve the social crisis in Italy, Germany, Spain, Poland, Finland, Rumania, and so on, by introducing fascism, while in the U.S. the imperialists resolved the social crisis with the New Deal. In Germany the workers were hit with the Gestapo, while in Amerika they got the C.I.O. industrial unions.

In that decade the white industrial proletariat unified itself, pushed aside the dead hand of the old A.F.L. labor aristocracy, and in a crushing series of sit-down strikes won tremendous increases in wages and working conditions. For the first time the new white industrial proletariat forced the corporations to surrender their despotic control over industrial life.

The Eastern and Southern European immigrant national minorities won the "better life" that Americanization promised them. They became full citizens of the U.S. empire, and, with the rest of the white industrial proletariat, won rights and privileges both inside and outside the factories. In return, as U.S. imperialism launched its drive for world hegemony, it could depend upon the armies of solidly united settlers serving imperialism at home and on the battlefield. To insure social stability, the new government-sponsored unions of the C. I .O. absorbed the industrial struggle and helped discipline class relations.

The working class upsurge of the 1930s was not accumulated discontents. This is the common, but shallow, view of mass outbreaks. What is true is that material conditions, including the relation to production, shape and reshape all classes and strata. These classes and strata then express characteristic political consciousness, characteristic roles in the class struggle.

The unification of the white industrial workforce was the result of immense pressures. Its long-range material basis was the mechanization and imperialist reorganization of production. In the late 19th century it was still true that in many industries the skilled craftsmen literally ran production. They - not the company - would decide how the work was done. Combining the functions of artisan, foreman, and personnel office, these skilled craftsmen would directly hire and boss their entire work crew of laborers, paying them out of a set fee paid by the capitalist per ton or piece produced (the balance being their wage-profit).

The master roller in the sheet metal rolling mill, the puddler in the iron mill, the buttie in the coal mine, the carriage builder in the early auto plant all exemplified this stage of production. The same craft system applied to gun factories, carpet mills, stone quarries etc. etc. (1) It was these highly privileged settler craftsmen who were the base of the old A.F.L. unions. Their income reflected their lofty positions above the laboring masses. In 1884, for example, master rollers in East St. Louis earned $42 per week (a then very considerable wage), over four times more than laborers they bossed. (2)

This petit-bourgeois income and role gradually crumbled as capitalists reorganized and seized ever tighter control over production. A survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor found that the number of skilled steel workers earning 60 cents an hour fell by 20% between 1900-1910. (3) Mechanization cut the ranks of craftsmen, and, even where they remained, their once-powerful role in production had shrunk. The A.F.L. Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, whose 24,000 members in 1891 accounted for 2/3rds of all craftsmen in the industry, had dwindled to only 6,500 members by 1914. (4) Mechanization also wiped out whole sections of the very bottom factory laborers, replacing shovels with mechanical scoops, wheelbarrows with electric trolleys and cranes. Both top and bottom layers of the factory workforce were increasingly pulled into the growing middle stratum of semi-skilled, production line assemblers and machine operators. In the modern auto plants of the 1920s some 70% were semi-skilled production workers, while only 10% were skilled craftsmen and 15% laborers. (5) The political unification of the white workers thus had its material roots in the enforced unification of labor in the modern factory.

The 1929 depression was also a great equalizer and a sharp blow to many settlers, knocking them off their conservative bias. During the 1930s roughly 25% of the U.S. Empire was unemployed. Office clerks, craftsmen, and college students rubbed shoulders with laborers and farmers in the relief lines. Many divisions broke down, as midwestern and Southern rural whites migrated to the industrial cities in search of jobs or relief. In 1929 it was estimated that in Detroit alone there were some 75,000 young men (the "Suitcase Brigade") who had come from the countryside to find jobs in the auto plants. (6)

The depression not only helped unite the settler workers, but the social catastrophe pushed large sections of other settler classes towards more sympathy with social reform. Small farmers were being forced wholesale into bankruptcy and were conducting militant struggles of their own. Professionals, intellectuals, and even many small businessmen, felt victimized by corporate domination of the economy. Militancy and radicalism became temporarily respectable. When white labor started punching out it would not only be stronger than before, but much of settler society would be sympathetic to it.

Citizenship in the Empire had very real but still limited meaning so long as many white workers remained "industrial slaves" of the corporations. The increasing centralization of monopoly capitalism repeated aspects of feudalism on a higher level. Both inside and outside the factory gates the settler workers were subject to heightened regimentation. During the 1920s it was not unusual for the persistent speed-up by management to double production per worker, even without taking mechanization into account.

At Ford, perhaps the most extreme of the industrial despots, every tenth employee was also a company spy. Workers overheard making resentful remarks would be beaten up right on the production line by the ever-present guards. (7) In the U.S. Steel plants at Homestead, Pa. the constant spying gave rise to a common saying: "If you want to talk in Homestead, you must talk to yourself." (8)

The Depression and the massive unemployment only threw more power into corporate hands. Not only were wages cut almost everywhere, but many companies laid off experienced workers and replaced them with newcomers at a fraction of the old wages. Ford Motor Company, which advertised that it was the highest paying company in the U.S., allegedly paid production workers a minimum of $7 per day (with inflation less than it paid in 1914). On the contrary, some thousands of Euro-American Ford employees in the '30s found their pay down as low as $1.40 per day; that was roughly what Afrikan women domestics had earned in Chicago. (9) It takes no genius to see that settler workers would not passively accept being reduced to a colonial wage. Companies in Detroit, Pitt- sburgh, etc. advertised widely in the South for workers, wishing even larger pools of jobless to intimidate and discipline their employees.

The A.F.L. unions were not only loyal to imperialism, but in their weakened state heavily dependent on enjoying the continued favors of individual corporations by opposing any real struggle. It was for that reason that the old Amalgamated Association had betrayed the 1919 steel strike. In that same year A.F.L. President Gompers 77 actually told the U.S. Senate that Prohibition was a danger, because alcohol was needed to get the workers' minds off rebellion. In the new auto industry the A.F.L. was receiving hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes from the auto manufacturers (usually via expensive advertisements in labor newspapers or "donations" to anticommunist campaigns). (10)

But when the dam broke, the pent-up anger of millions of Euro-Amerikan industrial workers was a mighty force. New organizing drives and new strikes had never completely stopped, even during the repressive 1920s. Defeat was common. But in 1934 two city-wide general strikes in San Francisco and Minneapolis, and a near-general strike in Toledo stunned capitalist Amerika.

The victory of longshoremen in San Francisco and teamsters in Minneapolis were important, but the Toledo auto workers strike - in which thousands of unemployed supporters of the auto workers drove the Ohio National Guard off the streets in direct battle - was the clearest sign of things to come. The victory in the Auto-Lite parts plant was immediately followed by union victories at all the other major factories in town. Toledo became in 1934 the first "union city" in industrial Amerika. The tidal wave of labor unrest affected all parts of the U.S. and all industries.

The new Sit-Down strikes became a rage. It was customary strategy for employers to break strikes by keeping the plants going with scabs, while hired thugs and police repressed the strike organization. But in the Sit-Downs the workers simply seized and occupied the plants, not only stopping production but threatening the bosses with physical destruction of their factories if they tried any repression. After so much abuse and powerlessness, militant young workers discovered great pleasure in temporarily taking over. In some strikes unlucky bands of foremen and company officials trapped in plant offices would become union prisoners for a few hours or days.

While 1935 and 1936 saw Sit-Down strikes in the rubber plants in Akron, Ohio, in auto plants in Detroit, Cleveland and Atlanta, it was the Dec. 1936 Flint, Michigan Sit-Down strike against GM that became the pivotal labor battle of the 1930s. Flint was the central fortress of GM production, their special company town where GM carefully kept both Afrikans and foreign-born immigrants to a minimum. Wages in the many Flint GM plants were relatively high for the times.

Still many enthusiastic Flint auto workers organized themselves around the new C.I.O. United Auto Workers union, and seized both Fisher Body No. 1 and Chevy No. 4 plants. Thousands of CIO militants from all over Michigan demonstrated in the streets as the Sit-Downers, armed with crowbars and bats, barricaded themselves into the plants. Since the first plant was the only source of Buick, Olds and Pontiac bodies, and the second plant was the only source of Chevrolet engines, the CIO Sit-Down strangled all GM car production. (11)

After 90 days of intense struggle around the seized plants, General Motors gave in. They recognized the UAW as the union representation in seventeen plants. This was the key victory of the entire Euro-Amerikan labor upsurge of the 1930s. It was obvious that if General Motors, the strongest corporation in the world, was unable to defeat the new industrial unions, then a new day had come. Practical advances by workers in auto, steel, rubber, electronics, maritime, meat-packing, trucking and so on, proved that this was so.

Ford workers at 1935 New Jersey CIO Convention, masked to avoid recognition by company spies.

The new union upsurge, which had begun in 1933, continued into the World War II period and the immediate post-war years. The number of strikes in the U.S. jumped from 840 in 1932 to 1700 in 1933, 2200 in 1936, and 4740 in 1937. By 1944 over 50% of auto workers took part in one or more strikes during the year. As many settler workers were taking part in strikes in 1944 as in 1937, at the height of the Sit-Downs. (12)

The defiant mood in the strongest union centers was very tangible. On March 14, 1944, some 5,000 Ford workers at River Rouge staged an "unauthorized" wildcat strike in which they blockaded the roads around the plant and broke into offices, "liberating" files on union militants. (13) It was common in "negotiations" for crowds of auto workers to surround the company officials or beat up company guards.

The substantial increases in wages and improvements in hours and working conditions were, for many, secondary to this new-found power in industrial life. In the great 1937 Jones & Laughlin steel strike in Aliquippa, Pa. - a company town ruled over by a near-fascistic company dictatorship - one striker commented on his union dues after the victory: "It's worth $12 a year to be able to walk down the main street of Aliquippa, talk to anyone you want about anything you like, and feel that you are a citizen." (14)

White Amerika reorganized then into the form we now know. The great '30s labor revolt was far more than just a series of factory disputes over wages. It was a historic social movement for democratic rights for the settler proletariat. Typically, these workers ended industrial serfdom. They won the right to maintain class organizations, to expect steady improvements in life, to express their work grievances, to accumulate some small property and to have a small voice in the local politics of their Empire.

In the industrial North the CIO movement reformed local school boards, sought to monitor draft exemptions for the privileged classes, ended company spy systems, replaced anti-union police officials, and in myriad ways worked to reorganize the U.S. Empire so that the Euro-Amerikan proletariat would have the life they expected as settlers. That is, a freer and more prosperous life than any proletariat in history has ever had.

The major class contradictions which had been developing since industrialization were finally resolved. The European immigrant proletariat wanted to fully become settlers, but at the same time was determined to unleash class struggle against the employers. Settler workers as a whole, with the Depression as a final push, were determined to overturn the past. This growing militancy made a major force of the settler workers. While they were increasingly united - "native-born" Euro-Amerikan and immigrant alike - the capitalists were increasingly disunited. Most were trying to block the way to needed reform of the U.S. Empire.

The New Deal administration of President Franklin Roosevelt reunited all settlers old and new. It gave the European "ethnic" national minorities real integration as Amerikans by sharply raising their privileges. New Deal officials and legislation promoted economic struggle and class organization by the industrial proletariat - but only in the settler way, in government-regulated unions loyal to U. S. Imperialism. President Roosevelt himself became the political leader of the settler proletariat, and used the directed power of their aroused millions to force through his reforms of the Empire.

Most fundamentally, it was only with this shakeup, these modernizing reforms, and the homogenized unity of the settler masses that U.S. Imperialism could gamble everything on solving its problems through world domination. This was the desperate preparation for World War. The global economic crisis after 1929 was to be resolved in another imperialist war, and the U.S. Empire intended to be the victor.

This social reunification could be seen in President Roosevelt's unprecedented third-term victory in the 1940 elections. Pollster Samuel Lubell analyzed the landslide election results for the Saturday Evening Post:

Roosevelt won by the vote of Labor, unorganized as well as organized, plus that of the foreign born and their first and second generation descendants. And the Negro.

It was a class-conscious vote for the first time in American history, and the implications are portentous. The New Deal appears to have accomplished what the Socialists, the I.W.W. and the Communists never could approach ... (15)

Lubell's investigation showed how, in a typical situation, the New Deal Democrats won 4 to 1 in Boston's "Charlestown" neighborhood; that was a working class and small petit-bourgeois "ethnic" Irish community. Of the 30,000 in the ward, almost every family had directly and personally benefited from their New Deal. Perhaps most importantly, the Democrats had very publicly "become the champion of the Irish climb up the American ladder." While Irish had been kept off the Boston U.S. Federal bench, Roosevelt promptly appointed two Irish lawyers as Federal judges. Other Irish from that 79 neighborhood got patronage as postmasters, U.S. marshals, collector of customs, and over 400 other Federal positions.

FDR meets with farm workers.

Irish workers in the neighborhood got raises from the new Federal minimum wage and hours law. Unemployment benefits went to those who were still jobless. 300-500 Irish youth earned small wages in the National Youth Administration, while thousands of adult jobless were given temporary Works Progress Administration (WPA) jobs. Forty per cent of the older Irish were on U.S. old-age assistance. 600 families got ADC. Many received food stamps. Federal funds built new housing and paid for park and beach improvements. The same process was taking place with Polish, Italian, Jewish and other European national minority communities throughout the North.

It was not just a crude bribery. The Depression was a shattering crisis to settlers, upsetting far beyond the turmoil of the 1960s and 1970s. It is hard for us to fully grasp how upside-down the settler world temporarily became. In the first week of his Administration, for example, President Roosevelt hosted a delegation of coal mine operators in the White House. They had come to beg the President to nationalize the coal industry and buy them all out. They argued that "free enterprise" had no hope of ever reviving the coal industry or the Appalachian communities dependent upon it.

Millions of settlers believed that only an end to traditional capitalism could make things run again. The new answer was to raise up the U.S. Government as the coordinator and regulator of all major industries. To restabilize the banking system, Roosevelt now insured consumer deposits and also sharply restricted many former, speculative bank policies. In interstate trucking, in labor relations, in communications, in every area of economic life new Federal agencies and bureaus tried to rationalize the daily workings of capitalism by limiting competition and stabilizing prices. The New Deal consciously tried to imitate the sweeping, corporate state economic dictatorship of the Mussolini regime in Italy.

The most advanced sections of the bourgeoisie - such as Thomas Watson of IBM and David Sarnoff of RCA - backed the controversial New Deal reforms. But for most the reaction was heated. The McCormick family's Chicago Tribune editorially called for Roosevelt's assassination. Those capitalists who most stubbornly resisted the changes were publicly denounced by the New Dealers, who had set themselves up as the leaders of the anti-capitalist mass sentiment.

The contradictions within the bourgeoisie became so great that a fascist coup d'etat was attempted against the New Deal. A group of major capitalists, headed by Irenee DuPont (of DuPont Chemicals) and the J.P. Morgan banking interests, set the conspiracy in motion in 1934. The DuPont family put up $3 million to finance a fascist stormtrooper movement, with the Remington Firearms Co. to arm as many as 1 million fascists. Gen. Douglas MacArthur was recruited to ensure the passive support of the U.S. Army. The plan was to seize state power, with a captive President Roosevelt forced to officially turn over the reins of government to a hand-picked fascist "strong-man.

As their would-be Amerikan Fuhrer the capitalists selected Gen. Smedley Butler, twice winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor and retired Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps. But after being approached by J.P. Morgan representatives, Gen. Butler went to Congress and exposed the cabal. An ensuing Congressional investigation confirmed Gen. Butler's story. With the conspiracy shot down and keeping in mind the high position of the inept conspirators, the Roosevelt Administration let the matter just fade out of the headlines.

During the 1936 election campaign one observer recorded the New Deal's open class appeal at a Democratic Party rally in Pittsburgh's Forbes Field. The packed crowd was whipped up by lesser politicians as they expectantly awaited the Presidential motorcade. State Senator Warren Roberts recited the names of famous millionaires, pausing as the crowds thundered boos after each name. He orated: "The President has decreed that your children shall enjoy equal opportunity with the sons of the rich." Then Pennsylvania Gov. Earle took the microphone to punch at the Republican capitalists even more:

There are the Mellons, who have grown fabulously wealthy from the toil of the men of iron and steel, the men whose brain and brawn have made this great city; Grundy, whose sweatshop operators have been the shame and disgrace of Pennsylvania for a generation; Pew, who strives to build a political and economic empire with himself as dictator; the DuPonts, whose dollars were earned with the blood of American soldiers; Morgan, financier of war.

Thousands of boos followed each name. Then, with the crowds worked up against their hated exploiters, the Presidential motorcade drove into the stadium to frenzied cheering. The observer wrote of Roosevelt's entry: "He entered in an open car. It might have been the chariot of a Roman Emperor." (17)

So it was not just the social concessions that the government made; the deep allegiance of the Euro- Arnerikan workers to this new Leader and his New Deal movement was born in the feeling that he truly spoke for their class interests. This was no accident. Nations and classes in the long run get the leadership they deserve.

In order to end the company-town feudalism of their communities, the CIO unionists took their new-found strength into the bourgeois political arena. The massed voting base of the new unions was the bedrock of the New Deal in the industrial states. The union activists themselves merged into and became part of the imperialist New Deal. Bob Travis, the Communist Party militant who was the organizer of the Flint Sit-Down, proudly told the 1937 UAW Convention:

We have also not remained blind to utilizing the city's political situation to the union's advantage, whenever possible. In this way, for five months after the strike, we were able to consolidate a 5-4 pro-labor majority bloc in the city commission, get a pro-labor city manager appointed, and bring about the dismissal of a vicious police chief, notorious as a strike-breaker.

By 1958, Robert Carter, the UAW Regional Director for Flint-Lansing, could resign to become Flint City Manager. Things had come full circle. Once outsiders challenging the local establishment, then angry reformers, the union was now part of the local bourgeois political structure.

This was the universal pattern in the industrial areas. In Anderson, Indiana, the auto workers at GM Guide Lamp took over the plant in a 1937 Sit-Down. By 1942, strike leader Riley Etchison was a member of the local draft board. Another Sit-Downer was the new sheriff. John Mullen, the Steelworkers union leader at U.S. Steel's Clairton, Pa. works, went on to become the Mayor, as did Steelworkers local leader Elmer Maloy in DuQuesne, Pa. Everywhere the young CIO activists integrated into the local Democratic Party as a force for patriotic reform.

Nor was this limited to Euro-Amerikans. Coleman Young (Mayor of Detroit), John Conyers (U.S. Congressman), and many other Afrikan politicians got their start as young CIO staff members. In Hawaii, the Japanese workers in the CIO International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union became the active base of the Democratic Party's takeover of Hawaiian bourgeois politics after the war. The CIO unions became an essential gear in the liberal reform machine of the Democratic Party. (18)

A significant factor in the success of the 1930s union organizing drives was the U.S. Government's refusal to use armed repression against it. No U.S. armed repression against Euro-Amerikan workers took place from January, 1933 (when Roosevelt took office) until the June, 1941 North American Aviation strike in California. The U.S. Government understood that the masses of Euro-Amerikan industrial workers were still loyal settlers, committed to U.S. Imperialism. To overreact to their economic struggles would only further radicalize them. Besides, why should President Roosevelt have ordered out the FBI or U.S. Army to break up the admiring supporters of his own Democratic Party?

Attempts by the reactionary wing of the bourgeoisie to return to the non-union past by wholesale repression were opposed by the New Deal. In the 1934 West Coast longshore strike (which in San Francisco became a general strike after the police killed two strikers), President Roosevelt refused to militarily intervene, despite the fact that the governors of Oregon and Washington requested that he do so.

In speaking for the shipping companies and business interests on the Coast, Oregon Gov. Meier telegraphed Roosevelt that troops were needed because: "We are now in a state of armed hostilities. The situation is complicated by communistic interference. It is now beyond the reach of State authorities...insurrection which if not checked will develop into civil war." Roosevelt publicly scorned this demand. It is telling that at the most violent period of the strike a picture of President Roosevelt hung in the longshoremen's union office in San Francisco.

President Roosevelt privately said in 1934 that there was a conspiracy by "the old conservative crowd" to provoke general strikes as a pretext for wholesale repression. The President's confidential secretary wrote at the time that both he and U.S. Labor Secretary Francis Perkins believed that: "...the shipowners deliberately planned to force a general strike throughout the country and in this way they hoped they could crush the labor movement. I have no proof but I think the shipowners were selected to replace the steel people who originally started out to do this job." (19)

The reactionary wing of the bourgeoisie were no doubt enraged at the New Deal's refusal to try and return the outmoded past at bayonet point. Almost three years later, in the pivotal labor battle of the 1930s, the New Deal forced General Motors to reach a deal with their striking Flint, Michigan employees. GM had attempted to end the Flint Sit-Down with force, using both a battalion of hired thugs and the local Flint police. Lengthy street battles with the police over union food deliveries to the Sit-Downers resulted in many strikers shot and beaten (14 were shot in one day), but also in union control over the streets. In the famous "Battle of Bull's Run" the auto workers, fighting in clouds of tear gas, forced the cops to run for their lives. The local repressive forces available to GM were unequal to the task.

From the second week of the strike, GM had officially asked the government to send in the troops. But both the State and Federal governments were in the hands of the New Deal. After five weeks of stalling, Michigan Gov. Frank Murphy finally sent in 1,200 National Guardsmen to calm the street battles but not to move against either the union or the seized plants. Murphy used the leverage of the troops to pressure both sides to reach a compromise settlement. The Governor reassured the CIO: "The military will never be used against you." The National Guard was ordered to use force, if necessary, to protect the Sit-Down from the local sheriff and any right-wing vigilantes.

The Administration had both the President's Secretary and the Secretary of Commerce call GM officials, urging settlement with the union. Roosevelt even had the head of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. call his friend, the Chairman of GM, to push for labor peace. The end of GM's crush-the-union strategy came on Feb. 11, 1937, after President Roosevelt had made it clear he would not approve repression, and told GM to settle with the union. GM realized that the fight was over. (20)

The important effect of the pro-CIO national strategy can be seen if we compare the '30s to earlier periods. Whenever popular struggles against business grew too strong to be put down by local police, then the government would send in the National Guard or U.S. Army. Armed repression was the drastic but brutally decisive weapon used by the bourgeoisie.

And the iron fist of the U.S. Government not only inspired terror but also promoted patriotism to split the settler ranks. The U.S. Army broke the great 1877 and 1894 national railway strikes. The coast-to-coast repressive wave, led by the U.S. Dept. of Justice, against the I.W.W. during 1917-1924 effectively destroyed that "Un-American" movement - even without Army troops. Yet, no such attempt was made during the even more turbulent 1930s. President Roosevelt himself turned to CIO leaders, in the words of the N. Y. Times, "for advice on labor problems rather than to any old-line A.F.L. leader." (21)

There was a heavy split in the capitalist class, with many major corporations viewing the CIO as the Red Menace in their backyards, and desperately using lockouts, company unions and police violence to stop them. Not all, however. Years before the CIO came into being, Gerald Swope of General Electric had told A.F.L. President William Green that the company would rather deal with one industrial union rather than fifteen different craft unions. And when the Communist Party-led United Electrical Workers-CIO organized at GE, they found that the company was glad to make a deal.

While some corporations, such as Republic Steel, tolerated unionization only after bloody years of conflict, others wised up very quickly. U.S. Steel tried to control its employees by promoting company unions. But in plant after plant the company unions were taken over by CIO activists. (23) It was no secret that the New Deal was pushing industrial unionization. In Aliquippa, Pa., Jones & Laughlin Steel Co. had simply made union militants "disappear" - one Steelworkers organizer was later found after having been secretly committed to a state mental hospital. New Deal Gov. Pinchot changed all that, even assigning State Police bodyguards to protect CIO organizers.

In Homestead, where no public labor meeting had been held since 1919, 2,000 steelworkers and miners gathered in 1936 in a memorial to the pioneering 1892 Homestead Strike against U.S. Steel. The memorial rally was protected by State Police, and Lt. Gov. Kennedy was one of the speakers. He told the workers that the State Police would help them if they went on strike against U.S. Steel. (24)

With all that, it is understandable that U.S. Steel decided to reach a settlement with the CIO. Two weeks after the Flint Sit-Down defeated GM, U.S. Steel suddenly proposed a contract to the CIO. On March 2, 1937, the Steelworkers Union became the officially accepted bargaining agent at U.S. Steel plants. The Corporation not only bowed to the inevitable, but by installing the CIO it staved off even more militant possibilities. The CIO bureaucracy was unpopular in the mills. Only 7% of the U.S. Steel employees had signed union membership cards. In fact, Lee Pressman, the Communist Party lawyer for the Steelworkers Union, said afterwards that they just didn't have the support of the majority:

'There is no question that we could not have filed a petition through the National Labor Relations Board or any other kind of machinery asking for an election. We could not have won an election ..." (25)

At the U.S. Steel stockholders meeting the following year, Chairman Myron Taylor explained to his investors why the New Deal's pro-CIO approach worked:

The union has scrupulously followed the terms of its agreement and, in so far as I know, has made no unfair effort to bring other employees into its ranks, while the corporation subsidiaries, during a very difficult period, have been entirely free of labor disturbance of any kind. (26)

By holding back the iron fist of repression, by encouraging the CIO, the New Deal reform government cut down "labor disturbance" among the Euro-Amerikan proletariat.

It should be kept in mind that the New Deal was ready to use the most direct repression when it was felt necessary. All during the 1930s, for example, they directed an ever-increasing offensive against the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico. Unlike the settler workers, the liberation struggle of Puerto Rico was not seeking the reform of the U.S. Empire but its ouster from their nation. The speed with which the nationalist fervor was spreading through the Puerto Rican masses alarmed U.S. Imperialism.

So the most liberal, most reform-minded U.S. Government in history repressed the Nationalists in the most naked and brutal way. By 1936 the tide of pro-Independence sentiment was running high, and Don Albizu Campos, President of the Nationalist Party, was without doubt the most respected political figure among both the intellectuals and the masses. School children were starting to tear the U.S. flag down from the school flagpoles and substitute the Puerto Rican flag. In the city of Ponce the school principal defied a police order to take the Puerto Rican banner down. The New Deal response was to directly move to violently break up the Nationalist center.

In July, 1936 eight Nationalist leaders were successfully tried for conspiracy by the U.S. Government. Since their first trial had ended in a dead-locked jury, the government decided to totally rig the next judge and jury (most of the jurors were Euro-Amerikans, for example). That done, the Nationalist leaders were sentenced to four to ten years in federal prison. Meanwhile, general repression came down. U.S. Governor Winship followed a policy of denying all rights of free speech or assembly to the pro-Independence forces. Machine guns were placed in the streets of San Juan.

On Palm Sunday, 1937 - one month after President Roosevelt refused to use force against the Flint Sit-Down Strike - the Ponce Massacre took place. A Nationalist parade, with a proper city permit, was met with U.S. police gunfire. The parade of 92 youth from the Cadets and Daughters of the Republic (Nationalist youth groups) was watched by 150 U.S. police with rifles and machine guns. As soon as the unarmed teen-agers started marching the police began firing and kept firing. Nineteen Puerto Rican citizens were killed and over 100 wounded. Afterwards, President Roosevelt rejected all protests and said that Governor Winship had his approval. The goal of paralyzing the pro-Independence forces through terrorism was obvious. (27)

Similar pressures, although different in form, were used by the New Deal against Mexicano workers in the West and Midwest. There, mass round-ups in the Mexicano communities and the forced deportation of 500,000 Mexicanos (many of whom had U.S. residency or citizenship) were used to save relief funds for settlers and, most importantly, to break up the rising Mexicano labor and national agitation. In a celebrated case in 1936, miner Jesus Pallares was arrested and deported for the "crime" of leading the 8,000-member La Liga Obrera De Habla Espanola in New Mexico. (28)

The U.S. Government used violent terror against the Puerto Rican people and mass repression against the Mexicano people during the 1930s. But it did nothing like that to stop Euro-Amerikan workers because it didn't have to. The settler working class wasn't going anywhere.

In the larger sense, they had little class politics of their own any more. President Roosevelt easily became their guide and Patron Saint, just as Andrew Jackson had for the settler workmen of almost exactly one century earlier. The class consciousness of the European immigrant proletarians had gone bad, infected with the settler sickness. Instead of the defiantly syndicalist I.W.W. they now had the capitalistic CIO.

This reflected the desires of the vast majority of Euro-Amerikan workers. They wanted settler unionism, with a privileged relationship to the government and "their" New Deal. Settler workers accepted each new labor law passed by the imperialist government to stabilize labor relations. But unions regulated, supervised and reorganized by the imperialists are hardly the free working class organizations called by that name in the earlier periods of world capitalism.

One reason that this CIO settler unionism was so valuable to the imperialists was that in a time of labor upheaval it cut down on uncontrolled militancy and even helped calm the production lines. Even the "Left" union militants were forced into this role. Bob Travis, the Communist Party leader of the 1937 Flint Sit-Down, reported only months after besting General Motors:

Despite this terrifically rapid growth in membership we have been able to conduct an intensive educational campaign against unauthorized strikes and for observation of our contract and in the total elimination of wild-cat actions during the past 3 months. (29)

Fortune, the prestigious business magazine, said in 1941:

...properly directed, the UAW can hold men together in an emergency; it can be made a great force for morale. It has regularized many phases of production; its shop stewards, who take up grievances on the factory floor, can smooth things as no company union could ever succeed in smoothing them. (30)

The Euro-Amerikan proletariat during the '30s had broken out of industrial confinement, reaching for freedoms and a material style of life no modern proletariat had ever achieved. The immense battles that followed obscured the nature of the victory. The victory they gained was the firm positioning of the Euro-Amerikan working class in the settler ranks, reestablishing the rights of all Europeans here to share the privileges of the oppressor nation. This was the essence of the equality that they won. This bold move was in the settler tradition, sharing the Amerikan pie with more European reinforcements so that the Empire could be strengthened. This formula had partially broken down during the transition from the Amerika of the Frontier to the Industrial Amerika. It was the brilliant accomplishment of the New Deal to mend this break.

I watched the first shipment of "repatriated" Mexicans leave Los Angeles in February, 1931. The loading process began a six o'clock in the morning. Repatriados arrived by the truckload - men, women, and children - with dogs, cats, and goats, half-open suitcases, rolls of bedding, and lunchbaskets. It cost the County of Los Angeles $77,249.29 to repatriate one trainload, but the savings in relief amounted to $347,468.41 for this one shipment. In 1932 alone over eleven thousand Mexicans were repatriated from Los Angeles...

The strikes in California in the thirties, moreover, were duplicated wherever Mexicans were employed in agriculture. Mexican fieldworkers struck in Arizona; in Idaho and Washington; in Colorado; in Michigan; and in the Lower Rio Grand Valley in Texas. When Mexican sheep-shearers went on strike in west Texas in 1934, one of the sheepmen made a speech in which he said: "We are a pretty poor bunch of white men if we are going to sit here and let a bunch of Mexicans tell us what to do."

With scarcely an exception, every strike in which Mexicans participated in the borderlands in the thirties was broken by the use of violence and was followed by deportations. In most of these strikes, Mexican workers stood alone; that is, they were not supported by organized labor, for their organizations, for the most part, were affiliated neither with the CIO nor the AFL.

Carey McWilliams, North from Mexico

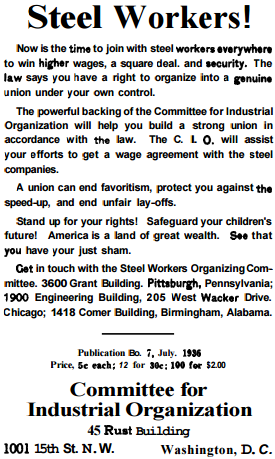

The CIO played an important role for U.S. imperialism in disorganizing and placing under supervision the nationally oppressed. For the first time masses of Third World workers were allowed and even conscripted into the settler trade unions. This was the result of a historic arrangement between the U.S. Empire and nationally oppressed workers in the industrial North.

On one side, this limited "unity" ensured that Third World workers didn't oppose the new, settler industrial unions, and were safely absorbed as "minorities" under tight settler control. On the other side, hungry Third World proletarians gained significant income advances and hopes of job security and advancement. It was an arrangement struck out of need on both sides, but one in which the Euro-Amerikan labor aristocracy made only tactical concessions while strengthening their hegemony over the Empire's labor market.

So while the old A.F.L. craft unions had controlled Third World labor by driving us out of the labor market, by excluding us from the craft unions or by confining us to small, "seg" locals, the new CIO could only control us by absorbing us into their settler unions. The imperialists had decided that they needed colonial labor in certain industries. Euro-Amerikan labor could not, therefore, drive the nationally oppressed away in the old manner. The colonial proletarians could only be controlled by disorganizing them - separating their economic struggles from the national struggles of their peoples, separating them from other Third World proletarians around the world, absorbing them as "brothers" of settler unionism, and placing them under the leadership of the Euro-Amerikan labor aristocracy. The new integration was the old segregation on a higher level, the unity of opposites in everyday life.

We can see how this all worked by reviewing the CIO's relationship to Afrikan workers. Large Afrikan refugee communities had formed in the major Northern industrial centers. Well over one million refugees had fled Northwards in just the time between 1910-1924, and new thousands came every month. They were an irritating presence to the settler North; each refugee community was a foreign body in a white metropolis. Like a grain of sand in an oyster. And just as the oyster eases its irritation by encasing the foreign element in a hard, smooth coating of pearl, settler Amerika encapsulated Afrikan workers in the hard, white layer of the CIO.

Despite the "race riots" and the hostility of Euro- Amerikans the Afrikan refugees streamed to the North in the early years of the century. After all, even the troubles of the North seemed like lesser evils to those fleeing the terroristic conditions of the occupied National Territory. Many had little choice, escaping the revived Ku Klux Klan. Increasingly forced off the land, barred from the new factories in the South, Afrikans were held down by the terroristic control of their daily lives.

Each night found the Illinois Central railroad wending its way Northward through Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee, following the Mississippi River up to the "Promised Land" of Gary or Chicago. Instead of sharecropping or seasonal farm labor for "Mr. John," Afrikan men during World War I might get hired for the "elite" Chicago jobs as laborers at Argo Corn Starch or International Harvester. Each week the Chicago Defender, in the '20s the most widely-read "race" newspaper even in the South, urged its readers to forsake hellish Mississippi and come Northward to "freedom." One man remembers the long, Mississippi nights tossing and turning in bed, dreaming about the fabled North: "You could not rest in your bed at night for Chicago."

The refugee communities were really small New Afrikan cities, where the taut rope of settler domination had been partially loosened. Spear's Black Chicago says: "In the rural South, Negroes were dependent upon white landowners in an almost feudal sense. Personal supervision and personal responsibility permeated almost every aspect of life ... In the factories and yards (of the North) on the other hand, the relationship with the 'boss' was formal and impersonal, and supervision limited to working hours." (31)

While there was less individual restriction, Afrikan refugees were under tight control as a national group. The free bourgeois labor market of Euro-Amerikans didn't really exist for Afrikans. Their employment was not individual, not private. They got work only when a company consciously decided to use Afrikan labor as a group. So that Afrikan labor in the industrial North still existed under colonial conditions, driven into specific workplaces and specific jobs.

Afrikans were understood by the companies as dynamite - extremely useful and potentially very dangerous. Their use in Northern industry was the start, though little understood at the time, of gradually bringing the new European immigrants up from proletarians to real settlers. Imperialism was gradually releasing the "Hunky" and "Dago" from laboring at the very bottom of the factories. Now even more Euro-Amerikans were being pushed upward into the ranks of skilled workers and supervisors. And if the Afrikan workers were paid more than their usual colonial wages in the South, they still earned less than "white man's wages." Even the newest European immigrant on the all-white production lines could look at the Afrikan laborers and know his new-found privileges as a settler.

The capitalists also knew that too many Afrikans might turn a useful and super-profitable tool into a dangerous force. Afrikan labor was used only in a controlled way, with heavy restrictions placed upon it. One Indiana steel mill superintendent in the 1920s said: "When we got (up to 10% Black) employees, I said, 'No more colored without discussion.' I got the colored pastors to send colored men whom they could guarantee would not organize and were not bolsheviks." This was at a time when the Garvey Movement, the all-Afrikan labor unions, and the growth of Pan-Afrikanist and revolutionary forces were taking place within the Afrikan nation.

The Northern factories placed strict quotas on the number of Afrikan workers. Not because they weren't profitable enough. Not because the employers were "prejudiced" - as the liberals would have it - but because the imperialists believed that Afrikan labor could most safely be used when it was surrounded by a greater mass of settler labor. In 1937 an official of the U.S. Steel Gary Works admitted that for the previous 14 years corporate policy had set the percentage of Afrikan workers at the mill to 15%. (32)

The Ford Motor Co. had perhaps the most extensive system of using Afrikan labor under plantation-like control, with Henry Ford acting as the planter. A special department of Ford management was concerned with dominating not only the on-the-job life of Afrikan workers, but the refugee community as well. Ford hired only through the Afrikan churches, with each church being given money if its members stayed obedient to Ford. The company also subsidized Afrikan bourgeois organizations. His Afrikan employees and their families constituted about one-fourth of the entire Detroit Afrikan community. Both the NAACP and the Urban League were singing Ford's praises, and warning Afrikan auto workers not to have anything to do with unions. One report on the Ford system in the 1930s said:

There is hardly a Negro church, fraternal body, or other organization in which Ford workers are not represented. Scarcely a Negro professional or business man is completely independent of income derived from Ford employees. When those seeking Ford jobs are added to this group, it is readily seen that the Ford entourage was able to exercise a dominating influence in the community. (33)

The Afrikan refugee communities, extensions of an oppressed nation, became themselves miniature colonies, with an Afrikan bourgeois element acting as the local agents of the foreign imperialists. Ford's system was unusual only in that one capitalist very conspicuously took as his role that which is usually done more quietly by a committee of capitalists through business, foundations and their imperialist government.

This colonial existence in the midst of industrial Amerika gave rise to contradiction, to the segregation of the oppressed creating its opposite in the increasingly important role of Afrikan labor in industrial production. Having been forced to concentrate in certain cities and certain industries and even certain plants, Afrikan labor at the end of the 1920's was discovered to have a strategic role in Northern industry far out of proportion to its still small numbers. In Cleveland Afrikans comprised 50% of the metal working industry; in Chicago they were 40-50% of the meat packing plants; in Detroit the Afrikan auto workers made up 12% of the workforce at Ford, 10% at Briggs, 30% at Midland Steel Frame. (34)

Just arrived in Chicago from the south.

Overall, Afrikan workers-employed in the industrial economy were concentrated in just five industries: automotive, steel, meat-packing, coal, railroads. The first four were where settler labor and settler capitalists were about to fight out their differences in the 1930s and early 1940s. And Afrikan labor was right in the middle.

In a number of industrial centers, then, the CIO unions could not be secure without controlling Afrikan labor. And on their side, Afrikan workers urgently needed improvement in their economic condition. A 1929 study of the automobile industry comments:

As one Ford employment official has stated, "Many of the Negroes are employed in the foundry and do work that nobody else would do." The writer noticed in one Chevrolet plant that Negroes were engaged on the dirtiest, roughest and most disagreeable work, for example, in the painting of axles. At the Chrysler plant they are used exclusively on paint jobs, and at the Chandler-Cleveland plant certain dangerous emery wheel grinding jobs were given only to Negroes. (35)

In virtually all auto plants Afrikans were not allowed to work on the production lines, and were segregated in foundry work, painting, as janitors, drivers and other "service" jobs. They earned 35-38 cents per hour, which was one-half of the pay of the Euro-Amerikan production line workers. This was true at Packard, at GM, and many other companies. (36)

The CIO's policy, then, became to promote integration under settler leadership where Afrikan labor was numerous and strong (such as the foundries, the meatpacking plants, etc.), and to maintain segregation and Jim Crow in situations where Afrikan labor was numerically lesser and weak. Integration and segregation were but two aspects of the same settler hegemony.

Three other imperatives shaped CIO policy:

To use the automobile industry as a case, there was considerable integration within the liberal United Auto Workers (UAW-CIO). That is, there was considerable recruiting of Afrikan labor to help Euro-Amerikan workers advance their particular class interests. The first Detroit Sit-Down was at Midland Steel Frame in 1936. The UAW not only recruited Afrikan workers to play an active role in the strike, but organized their families into the CIO support campaign. Midland Frame, which made car frames for Chrysler and Ford, was 30% Afrikan. There the UAW had no reasonable chance of victory without commanding Afrikan forces as well as its own.

But at the many plants that were overwhelmingly settler, the CIO obviously treated Afrikan labor differently. In those majority of the situations the new union supported segregation. In Flint, Michigan the General Motors plants were Jim Crow. Afrikans were employed only in the foundry or as janitors, at sub-standard wages (many, of course, did other work although still officially segregated and underpaid as "janitors"). Not only skilled jobs, but even semi-skilled production line assembly work was reserved for settlers.

While the UAW fought GM on wages, hours, civil liberties for settler workers, and so forth, it followed the general relationship to colonial labor that GM had laid down. So that the contradiction between settler labor and settler capitalists was limited, so to say, to their oppressor nation, and didn't change their common front towards the oppressed nations and their proletariats. At the time of the Flint Sit-Down victory in February, 1937, the NAACP issued a statement raising the question of more jobs: "Everywhere in Michigan colored people are asking whether the new CIO union is going to permit Negroes to work up into some of the good jobs or whether it is just going to protect them in the small jobs they already have in General Motors." (37)

That was an enlightening question. Many UAW radicals had already answered "yes." Wyndham Mortimer, the Communist Party USA trade union leader who was 1st Vice-President of the new UAW-CIO, left behind a series of autobiographical sketches of his union career when he died. Beacon Press, the publishing house of the liberal Unitarian-Universalist Church, has printed this autobiography under the stirring title Organize! In his own words Mortimer left us an inside view of his secret negotiations with Afrikan auto workers in Flint.

Mortimer had made an initial organizing trip to Flint in June, 1936, to start setting up the new union. Anxious to get support from Afrikan workers for the coming big strike, Mortimer arranged for a secret meeting:

A short time later, I found a note under my hotel room door. It was hard to read because so many grimy hands had handled it. It said, "Tonight at midnight," followed by a number on Industrial Avenue. It was signed, "Henry." Promptly at midnight, I was at the number he had given. It was a small church and was totally dark. I rapped on the door and waited. Soon the door was opened and I went inside. The place was lighted by a small candle, carefully shaded to prevent light showing. Inside there were eighteen men, all of them Negroes and all of them from the Buick foundry. I told them why I was in Flint, what I hoped to do in the way of improving conditions and raising their living standards. A question period followed. The questions were interesting in that they dealt with the union's attitude toward discrimination and with what the union's policy was toward bettering the very bad conditions of the Negro people. One of them said, "You see, we have all the problems and worries of the white folks, and then we have one more: we are Negroes."

I pointed out that the old AFL leadership was gone. The CIO had a new program with a new leadership that realized that none of us was free unless we were all free. Part of our program was to fight Jim Crow. Our program would have a much better chance of success if the Negro worker joined with us and added his voice and presence on the union floor. Another man arose and asked, "Will we have a local union of our own?" I replied, "We are not a Jim Crow union, nor do we have any second-class citizens in our membership!" "The meeting ended with eighteen application cards signed and eighteen dollars in initiation fees collected. I cautioned them not to stick their necks out, but quietly to get their fellow workers to sign application cards and arrange other meetings... (38)

Mortimer's recollections are referred to over and over in Euro-Amerikan "Left" articles on the CIO as supposed fact. In actual fact there was little Afrikan support for the Flint Sit-Down. Only five Afrikans took part in the Flint Sit-Down Strike. Nor was that an exception. In the 1937 Sit-Down at Chrysler's Dodge Main in Detroit only three Afrikan auto workers stayed with the strike. During the critical, organizing years of the UAW, Afrikan auto workers were primarily sitting out the fight between settler labor and settler corporations. (39) It was not their nation, not their union, and not their fight. And the results of the UAW-CIO victory proved their point of view.

The Flint Sit-Down was viewed by Euro-Amerikan workers there as their victory, and they absolutely intended to eat the dinner themselves. So at Flint's Chevrolet No. 4 factory the first UAW & GM contract after the Sit-Down contained a clause on "noninterchangibility" reaffirming settler privilege. The new union now told the Afrikan workers that the contract made it illegal for them to move up beyond being janitors or foundry workers. That was the fruit of the great Flint Sit-Down - a Jim Crow labor contract. (40) The same story was true at Buick, exposing how empty were the earlier promises to Afrikan workers.

This was not limited to one plant or one city. A history of the UAW notes: "As the UAW official later conceded...in most cases the earliest contracts froze the existing pattern of segregation and even discrimination'." (41) At the Atlanta GM plant, whose 1936 Sit-Down strike is still pointed to by the settler "Left" as an example of militant "Southern labor history," only total white-supremacy was good enough for the CIO workers. The victorious settler auto workers not only used their new-found union power to restrict Afrikan workers to being janitors, but did away altogether with even the pretense of having them as union members. For the next ten years the Atlanta UAW was all-white. (42)

So in answer to the question raised in 1937 by the NAACP, the true answer was "no" - the new CIO auto workers union was not going to get Afrikans more jobs, better jobs, an equal share of jobs, or any jobs. This was not a "sell-out" by some bureaucrat, but the nature of the CIO. Was there a big struggle by union militants on this issue? No. Did at least the Euro-Amerikan "Left" - there being many members in Flint, for example, of the Communist Party USA, the Socialist Party, and the various Trotskyists - back up their Afrikan "union brothers" in a principled way? No.

It is interesting that in his 1937 UAW Convention report on the Flint Victory, Communist Party USA militant Bob Travis covered up the white-supremacist nature of the Flint CIO. In his report (which covers even such topics as union baseball leagues) there was not one word about the Afrikan GM workers and the heavy situation they faced. And if that was the practice of the most advanced settler radicals, we can well estimate the political level of the ordinary Euro-Amerikan worker.

Neither integration nor segregation was basic - oppressor nation domination was basic. If the UAW-CIO practiced segregation on a broad scale, it was equally prepared to use integration. When it turned after cracking GM and Chrysler to confront Ford, the most strongly anti-union of the Big Three auto companies, the UAW had to make a convincing appeal to the 12,000 Afrikan workers there. So special literature was issued, Afrikan church and civil rights leaders negotiated with, and - most importantly - Afrikan organizers were hired by the CIO to directly win over their brothers at Ford.

The colonial labor policy for the U.S. Empire was, as we previously discussed, fundamentally reformed in the 1830s. The growing danger of slave revolts and the swelling Afrikan majority in many key cities led to special restrictions on the use of Afrikan labor. Once the mainstay of manufacture and mining, Afrikans were increasingly moved out of the urban economy. When the new factories spread in the 1860s, Afrikans were kept out in most cases. The general colonial labor policy of the U.S. Empire has been to strike a balance between the need to exploit colonial labor and the safeguard of keeping the keys to modern industry and technology out of colonial hands.

On an immediate level Afrikan labor - as colonial subjects - were moved into or out of specific industries as the U.S. Empire's needs evolved. The contradiction between the decision to stabilize the Empire by giving more privilege to settler workers (ultimately by deproletarianizing them) and the need to limit the role of Afrikan labor was just emerging in the early 20th century.

So the CIO did not move to oppose open, rigid segregation in the Northern factories until the U.S. Government told them to during World War II. Until that time the CIO supported existing segregation, while accepting those Afrikans as union members who were already in the plants. This was only to strengthen settler unionism's power on the shop floor. During its initial 1935-1941 organizing period the CIO maintained the existing oppressor nation/oppressed nations job distribution: settler workers monopolized the skilled crafts and the mass of semi-skilled production line jobs, while colonial workers had the fewer unskilled labor and broom-pushing positions.

For its first seven years the CIO not only refused to help Afrikan workers fight Jim Crow, but even refused to intervene when they were being driven out of the factories. Even as the U.S. edged into World War II many corporations were intensifying the already tight restrictions on Afrikan labor. Now that employment was picking up with the war boom, it was felt not only that Euro-Amerikans should have the new jobs but that Afrikans were not yet to be trusted at the heart of the imperialist war industry.

Robert C. Weaver of the Roosevelt Administration admitted: "When the defense program got under way, the Negro was only on the sidelines of American industry, he seemed to be losing ground daily." Chrysler had decreed that only Euro-Amerikans could work at the new Chrysler Tank Arsenal in Detroit. Ford Motor Co. was starting many new, all-settler departments - while rejecting 99 out of 100 Afrikan men referred to Ford by the U.S. Employment Service. And up in Flint, the 240 Afrikan janitors at Chevrolet No. 4 plant learned that GM was going to lay them off indefinitely. During 1940 and early 1941, while settler workers were being rehired for war production in great numbers, Afrikan labor found itself under attack. (43)

Those Afrikan workers employed in industry could not defend their immediate class interests through the CIO, but had to step out of the framework of settler unionism just to defend their existing jobs. In the Summer of 1941 there were three Afrikan strikes at Dodge Main and Dodge Truck in Detroit. The Afrikan workers at Flint Chevrolet No.4 staged protest rallies and eventually won their jobs. As late as April 1943 some 3,000 Afrikan workers at Ford went out on strike for three days toprotest Ford's hiring policies. The point is that the CIO opposed Afrikan interests because it followed imperialist colonial labor policy - and when Afrikan workers needed to defend their class interests they had to do so on their own, organizing themselves on the basis of nationality.

It was not until mid-1942 that the CIO and the corporations, maneuvering together under imperialist coordination, started tapping Afrikan labor for the production lines. As much as settlers disliked letting masses of Afrikans into industry, there was little choice. The winning of the entire world was at stake, in a "rule or ruin" war. As the U.S. Empire strained to put forth great armies, navies and air fleets to war on other continents, the supply of Euro-Amerikan labor had reached the bottom of the barrel. To U.S. Imperialism, if the one-and-half million Afrikan workers in war industry helped the Empire conquer Asia and Europe it would well be worth the price.

The U.S. War Production Board said: "We cannot afford the luxury of thinking in terms of white men's work." So the numbers of Afrikan workers on the production lines tripled to 8.3% of all manufacturing production workers. Now the CIO unions, however unhappily, joined the corporations in promoting Afrikans into new jobs - even as hundreds of thousands of settler workers were protesting in "hate strikes." The reality was that settler workers had government-led, imperialist unions, while colonial workers had no unions of their own at all. (44)

During World War II the CIO completed integrating itself by picking up many hundreds of thousands of colonial workers. Many of these new members, we should point out, were involuntary members. Historically, the overwhelming majority of Afrikans who have belonged to the CIO industrial unions in the past 40 years never joined voluntarily. Starting with the first Ford contract in 1941, the CIO rapidly shifted to "union shop" contracts. In these contracts all new employees were required to join the union as a condition of employment. The modern imperialist factory in most industries quickly became highly unionized - whether any of us liked it or not.

The U.S. Government, depending on the CIO as a key element in labor discipline, encouraged the "union shop." The U.S. War Labor Board urged corporations to thus force their employees to join the CIO: "Too often members of unions do not maintain their membership because they resent discipline of responsible leadership." (45) While this applied to all industrial workers, it applied most heavily to colonial labor.

The government and the labor aristocracy were impatient to get colonial workers safely tied up. If they were to be let into industry in large numbers they had to be split up and neutralized by the settler unions - voluntarily or involuntarily. In the Flint Buick plant, where 588 of the 600 Afrikan workers had been segregated in the foundry despite earlier CIO promises, the union and GM expected to win them over by finally letting them work on the production lines. To their surprise, as late as mid-1942 the majority of the Afrikan workers still refused to join the CIO. (46) The Afrikan Civil Rights organizations, the labor aristocracy, and the liberal New Deal all had to "educate" resisting workers like those to get in line with the settler unions.

The integration of the CIO, therefore, had nothing to do with increasing job opportunities for Afrikans or building "working class unity." It was a new instrument of oppressor nation control over the oppressed nation proletarians.