Cherokee Nation on "Trail of Tears" - 1838 (source)

Settler Amerika got the reinforcements it needed to advance into Empire from the great European immigration of the 19th Century. Between 1830-1860 some 4.5 Million Europeans (two-thirds of them Irish and German) arrived to help the settler beachhead on the Eastern shore push outward.(1) The impact of these reinforcements on the tide of battle can be guessed from the fact that they numbered more than the total settler population of 1800. At a time when the young settler nation was dangerously dependent on the rebellious Afrikan colony in the South, and on the continental battleground greatly outnumbered by the various Indian, Mexican and Afrikan nations, these new legions of Europeans played a decisive role.

The fact that this flood of new Europeans also helped create contradictions within the settler ranks has led to honest confusions. Some comrades mistakenly believe that a white proletariat was born, whose trade-union and socialist activities placed it in the historic position of a primary force for revolution (and thus our eventual ally). The key is to see what was dominant in the material life and political consciousness of this new labor stratum, then and now.

The earlier settler society of the English colonies was relatively "fluid" and still unformed in terms of class structure. After all, the original ruling class of Amerika was back in England, and even the large Virginia planter capitalists were seen by the English aristocracy as mere middle-men between them and the Afrikan proletarians who actually created the wealth. To them George Washington was just an overpaid foreman. And while there were great differences in wealth and power, there was a shared privilege among settlers. Few were exploited in the scientific socialist sense of being a wage-slave of capital; in fact, wage labor for another man was looked down upon by whites as a mark of failure (and still is by many). Up until the mid-1800's settler society then was characterized by the unequal but general opportunities for land ownership and the extraordinary fluidity of personal fortunes by Old European standards.

This era of early settlerism rapidly drew to a close as Amerikan capitalism matured. Good Indian land and cheap Afrikan slaves became more and more difficult for ordinary settlers to obtain. In the South the ranks of the planters began tightening, concentrating as capital itself was. One historian writes:

"During the earlier decades, when the lower South was being settled, farmers stood every chance of becoming planters. Until late in the fifties (1850's - ed.) most planters or their fathers before them started life as yeomen, occasionally with a few slaves, but generally without any hands except their own. The heyday of these poor people lasted as long as land and slaves were cheap, enabling them to realize their ambition to be planters and slaveowners as so many succeeded in doing...But the day of the farmer began to wane rapidly after 1850. If he had not already obtained good land, it became doubtful he could ever improve his fortunes. All the fertile soil that was not under cultivation was generally held by speculators at mounting prices."(2)

While in the cities of the North, the small, local business of the independent master craftsman (shoemaker, blacksmith, cooper, etc.) was giving way step by step to the large merchant, with his regional business and his capitalist workshop/factory. This was the inevitable casualty list of industrialism. At the beginning of the 1800's it was still true that every ambitious, young Euro-Amerikan apprentice worker could expect to eventually become a master, owning his own little business (and often his own slaves). There is no exaggeration in saying this. We know, for example, that in the Philadelphia of the 1820's craft masters actually outnumbered their journeymen employees by 3 to 2 - and that various tradesmen, masters and professionals were an absolute majority of the Euro-Amerikan male population. (3)

But by 1860 the number of journeymen workers compared to masters had tripled, and a majority of Euro-Amerikan men were now wage-earners.(4) Working for a master or merchant was no longer just a temporary stepping-stone to becoming an independent landowner or shopkeeper. This new white workforce for the first time had little prospect of advancing beyond wage-slavery. Unemployment and wage-slashing were common phenomena, and an increasing class strife and discontent entered the world of the settlers.

In this scene the new millions of immigrant European workers, many with Old European experiences of class struggle, furnished the final element in the hardening of a settler class structure. The political development was very rapid once the nodal point was reached: From artisan guilds to craft associations to local unions. National unions and labor journals soon appeared. And in the workers' movements the championing of various socialist and even Marxist ideas was widespread and popular, particularly since these immigrant masses were salted with radical political exiles (Marx, in the Inaugural Address to the 1st International in 1864, says: "...crushed by the iron hand of force, the most advanced sons of labor fled in despair to the transatlantic Republic...")

All this was but the outward form of proletarian class consciousness, made all the more convincing because those white workers subjectively believed that they were proletarians - "the exploited", "the creators of all wealth", "the sons of toil", etc. etc. In actuality this was clearly untrue. While there were many exploited and poverty-stricken immigrant proletarians, these new Euro Amerikan workers as a whole were a privileged labor stratum. As a labor aristocracy it had, instead of a proletarian, revolutionary consciousness, a petit-bourgeois consciousness that was unable to rise above reformism.

This period is important for us to analyze, because here for the first time we start to see the modern political form of the Euro-Amerikan masses emerge. Here, at the very start of industrial capitalism, are trade-unions, labor electoral campaigns, "Marxist" organizations, nation-wide struggles by white workers against the capitalists, major proposals for "White and Negro" labor alliance.

What we find is that this new class of white workers was indeed angry and militant, but so completely dominated by petit-bourgeois consciousness that they always ended up as the pawns of various bourgeois political factions. Because they clung to and hungered after the petty privileges derived from the loot of empire, they as a stratum became rabid and reactionary supporters of conquest and the annexation of oppressed nations. The "trade-union unity" deemed so important by Euro-Amerikan radicals (then and now) kept falling apart and was doomed to failure. Not because white workers were racist (although they were), but because this alleged "trade-union unity" was just a ruse to divide, confuse and stall the oppressed until new genocidal attacks could be launched against us, and completely drive us out of their way.

This new stratum, far from possessing a revolutionary potential, was unable to even take part in the democratic struggles of the 19th century. When we go back and trace the Euro-Amerikan workers' movements from their early stages in the pre-industrial period up thru the end of the 19th Century, this point is very striking.

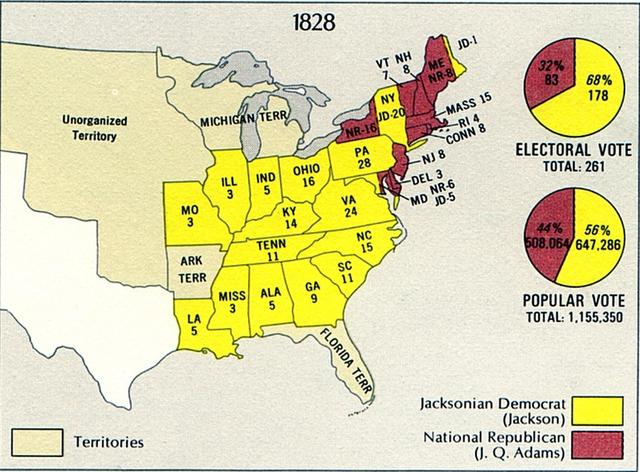

In the 1820's-30's, before white workers had even developed into a class, they still played a major role in the political struggles of “Jacksonian Democracy”. At that time the "United States" was a classic bourgeois democracy - that is, direct "democracy" for a handful of capitalists. Even among settlers, high property qualifications, residency laws and sex discrimination limited the vote to a very small minority. So popular movements, based among angry small farmers and urban workingmen, arose in state after state to strike down these limitations - and thus force settler government to better share the spoils of empire.

In New York State, for example, one liberal landmark was the "Reform Convention" of 1821, where the supporters of Martin Van Buren swept away the high property qualifications that had previously barred white workingmen from voting. This was a significant victory for them. Historian Leon Litwack has pointed out that the 1821 Convention "has come to symbolize the expanded democracy which made possible the triumph of Andrew Jackson seven years later." Van Buren became the hero of the white workers, and was later to follow Jackson into the White House.(5)

Did this national trend "for the extension and not the restriction of popular rights" (to quote the voting rights committee of the Convention) involve the unity of Euro-Amerikan and Afrikan workers? No. In fact, the free Afrikan communities in the North opposed these reform movements of the settler masses. The reason is easy to grasp: Everywhere in the North, the pre-Civil War popular struggles to enlarge the political powers of the settler masses also had the program of taking away civil rights from Afrikans. These movements had the public aim of driving all Afrikans out of the North. The 1821 New York "Reform Convention" gave all white workingmen the vote, while simultaneously raising property qualifications for Afrikan men so high that it effectively disenfranchised the entire community. By 1835 it was estimated that only 75 Afrikans out of 15,000 in that state had voting rights.(6)

This unconcealed attack on Afrikans was in point of fact a compromise, with Van Buren restraining the white majority which hated even the few, remaining shreds of civil rights left for well-to-do Afrikans. Van Buren paid for this in his later years, when opposing politicians (such as Abraham Lincoln) attacked him for letting any Afrikans vote at all. For that matter, this new, expanded settler electorate in New York turned down bills to let Afrikans vote for many years thereafter. In the 1860 elections while Lincoln and the G.O.P. were winning New York by a 32,000 vote majority, only 1,600 votes supported a bill for Afrikan suffrage. Frederick Douglass pointed out that civil rights for Afrikans was supported by "neither Republicans nor abolitionists".(7)

These earlier popular movements of settler workingmen found significant expression in the Presidency of Andrew Jackson, the central figure of “Jacksonian Democracy”. This phrase is used by historians to designate the rabble-rousing, anti-elite reformism he helped introduce into settler politics. His role in the early political stirrings of the white workers was so large that even today some Euro-Amerikan "Communist" labor historians proudly refer to "the national struggle for economic and political democracy led by Andrew Jackson."(8)

Jackson did indeed lead a "national struggle" to enrich not only his own class (the planter bourgeoisie) but his entire settler nation of oppressors. He stood at a critical point in the great expansion into Empire. During his two administrations he personally led the campaigns to abolish the National Bank (which was seen by many settlers as protecting the monopolistic power of the very few top capitalists and their British and French backers) and to ensure settler prosperity by annexing new territory into the Empire. In both he was successful.

The boom in slave cotton and the parallel rise in immigrant European labor was tied to the removal of the Indian nations from the land. After all, the expensive growth of railroads, canals, mills and workshops was only possible with economic expansion - an expansion that could only come from the literal expansion of Amerika through new conquests. And the fruits of new conquests were very popular with settlers of all strata, North and South. The much-needed expansion of cash export crops (primarily cotton) and trade was being blocked as the settled land areas ran up against the Indian-U.S. Empire borders. In particular, the so-called "Five Civilized Nations" (Creeks, Cherokees, Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Seminoles), Indian nations that had already been recognized as sovereign territorial entities in U.S. treaties, held much of the South: Northern Georgia, Western North Carolina, Southern Tennessee, much of Alabama and two-thirds of Mississippi.(9)

The settlers were particularly upset that the Indian nations of the Old Southwest showed no signs of collapsing, "dying out" or trading away their land. All had developed stable and effective agricultural economies, with considerable trade. Euro-Amerikans, if anything, thought that they were too successful. The Cherokee, who had chosen a path of adopting many Western societal forms, had a national life more stable and prosperous than that of the Euro-Amerikan settlers who eventually occupied those Appalachian regions after they were forced out. A Presbyterian Church report in 1826 records that the Cherokee nation had: 7,600 houses, 762 looms, 1488 spinning wheels, 10 sawmills, 31 grain mills, 62 blacksmith shops, 18 schools, 70,000 head of livestock, a weekly newspaper in their own language, and numerous libraries with "thousands of good books". The Cherokee national government had a two-house legislature and a supreme court.(10)

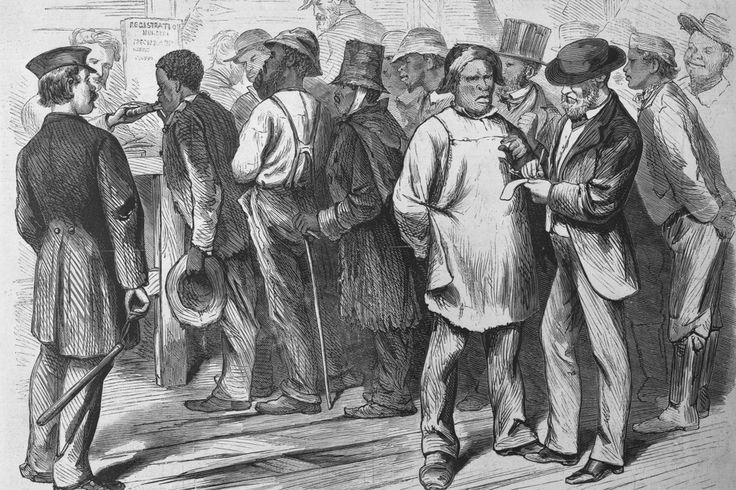

Cherokee Nation on "Trail of Tears" - 1838 (source)

Under the leadership of President Jackson, the U.S. Government ended even its limited recognition of Indian sovereignty, and openly encouraged land speculators and local settlers to start seizing Indian land at gunpoint. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling upholding Cherokee sovereignty vs. the state of Georgia was publicly ridiculed by Jackson, who refused to enforce it. In 1830 Jackson finally got Congress to Pass the Removal Act, which authorized him to use the army to totally relocate or exterminate all Indians east of the Mississippi River. The whole Eastern half of this continent was now to be completely cleared of Indians, every square inch given over to the needs of European settlers. In magnitude this was as sweeping as Hitler's grand design to render continental Europe "free" of Jews. Under Jackson's direction, the U.S. Army committed genocide on an impressive scale. The Cherokee Nation, for instance, was dismantled, with one-third of the Cherokee population dying in the Winter of 1838 (from disease, famine, exposure and gunfire as the U.S. Army marched them away at bayonet point on "The Trail of Tears").(11)

So the man who led the settler's "national struggle for economic and political democracy" was not only a bourgeois politician, but in fact an apostle of annexation and genocide. The President of "The Trail of Tears" was a stereotype frontiersman - a fact which made him popular with poorer whites. After throwing away his inheritance on drinking and gambling, the young Jackson moved to the frontier (at that time Nashville, Tenn.) to "find his fortune". That's a common phrase in the settler history books, which only conceals the reality that the only "fortune" on the frontier was from genocide. Jackson eventually became quite wealthy through speculating in Indian land (like Washington, Franklin and other settlers before him) and owning a cotton plantation with over one hundred Afrikan slaves. The leader of “Jacksonian Democracy” had a clear, practical appreciation of how profitable genocide could be for settlers.

First as a land speculator, then as slavemaster, and finally as General and then President, Jackson literally spent the whole of his adult life personally involved in genocide. During the Creek War of 1813-14 Jackson and his fellow frontiersmen slaughtered hundreds of unarmed women and children - afterwards skinning the bodies to make souvenirs*.(12) [* While some of Hitler's Death Camp officers are said to have made lampshades out of the skins of murdered Jews, the practicalities of frontier life led Jackson and his men to make bridle reins out of their victim's skins.] Naturally, Jackson had a vicious hatred of Indians and Afrikans. He spent the majority of his years in public office pressing military campaigns against the Seminole in Florida, who had earned special enmity by sheltering escaped Afrikans. U.S. military campaigns in Florida against first the Spanish and then the Seminole, were in large part motivated by the need to eliminate this land base for independent Afrikan regroupment.

The Seminole Wars that went on for over 30 years began when Jackson was an army officer and ended after he had retired from the White House - though he still sent Washington angry letters of advice on the war from his retirement. They were as much Afrikan wars as Indian wars, for the escaped Afrikans had formed liberated Afrikan communities as a semi-autonomous part of the sheltering Seminole Nation.(13)

The first attacks on these Afrikan-Seminole took place in 1812-14, when Georgia vigilantes invaded to enslave the valuable Afrikans. Afrikan forces wiped out almost all of the invaders (including the commanding Georgia major and a U.S. General). Two years later, in 1816, U.S. naval gunboats successfully attacked the Afrikan Ft. Appalachicola on the Atlantic Coast; two hundred defenders were killed when a lucky shot touched off the Afrikan ammunition stores. The next year, in 1817, army troops under Jackson's command invaded Florida in the First Seminole War. The Afrikans and Seminoles evaded Jackson's troops and permanently withdrew deeper into Central Florida.

Popular and electoral vote in the election of 1828. (source)

The decisive Second Seminole War began in 1835 when the Seminole Nation, under the leadership of the great Osceola, refused to submit to U.S. removal to Oklahoma. A key disagreement was that the settlers insisted on their right to separate the Seminole from their Afrikan co-citizens, who would then be reenslaved and put on the auction block. When the Seminole refused, Jackson angrily ordered the Army to go in and "eat (Osceola) and his few". Fighting a classic guerrilla war, 2000 Seminole and 1000 Afrikan fighters inflicted terrible casualties on the invading U.S. Army. Even capturing Osceola in a false truce couldn't give the settlers victory.

Finally, U.S. Commanding General Thomas Jesup conceded that none of the Afrikans would be reenslaved, but all could relocate to Oklahoma as part of the Seminole Nation. With this most of the Seminole and Afrikan forces surrendered and left Florida.* [* Even in the Oklahoma Territory, repeated outbreaks of guerrilla campaigns by Afrikan-Seminole forces were reported as late as 1842.] Those who refused to submit simply retreated deeper into the Everglades and kept ambushing any settlers who dared to follow. In 1843 the U.S. gave up trying to root the remaining Seminole guerrillas out of the swamps.

The settlers lost some 1,600 soldiers killed and additional thousands wounded or disabled through disease. The war - which Gen. Jesup labelled "a Negro, not an Indian, war - cost the U.S. some $30 Million. That was eighty times what President Jackson had promised Congress he would spend in getting rid of all Indians East of the Mississippi. By the time he left office, Jackson was infuriated that the Seminole and Afrikans were resisting the armed might of the Empire year after year. He urged that the Army concentrate on finding and killing all the enemy women, in order to put a final, biological end to this stubborn Nation. He boasted that he had used this strategy quite successfully in his own campaigns against Indians.(14)

Time and again Jackson made it clear that he favored a "Final Solution" of total genocide for all Indians. In his second State of the Union Address, Jackson reassured his fellow settlers that they should not feel guilty when they "tread on the graves of extinct nations", since the wiping out of all Indian life was just as "natural" as the passing of generations! Could anyone miss the point? After years and decades soaked in aggression and killing, could any Euro-Amerikan not know what Jackson stood for? Yet he was the chosen hero of the Euro-Amerikan workers of that day.

While Hitler never won an election in his life - and had to use the armed power of the state to violently crush the German workers and their organizations - Jackson was swept into power by the votes of Euro-Amerikan workmen and small farmers. His jingoistic expansionism was popular with all sectors of settler society, in particular with those who planned to use Indian land to help solve settler economic troubles. Northern workers praised him for his opposition to the old colonial elite of the Federalist Party, his stand on the National Bank, and his famous "Equal Protection Doctrine". The later piously declaimed that government's duty was not to favor the rich, but through taxation and other measures to give aid "alike on the high and low, the rich and the poor..." of settler society.(15)

Jackson was the historic founder of today's Democratic Party; not only in organization, but in first welding together the electoral coalition of Southern planters and Northern "ethnic" workers. He was the first President to claim that he was born in a log cabin, of lowly circumstances. This "redneck" posture, enhanced by his bloody military adventures, was very popular with the mass of small slave-owners in his native South - and with Northern workers as well! Detailed voting studies confirm that in both the 1828 and 1832 elections, Jackson received the overwhelming majority of the votes of immigrant Irish and German workers in the North.(16) White workmen joined his Democratic Party as a new crusade for equality among settlers. In the New York mayoral election of 1834, organized white labor marched in groups to the polls singing:

Mechanics, cartmen, laborers

Must form a close connection,

And show the rich Aristocrats,

Their powers at this election...

Yankee Doodle, smoke 'em out

The Proud, the banking faction.

None but such as Hartford Feds

Oppose the poor and Jackson...(17)

Underneath the surface appearance of militant popular reform, of workers taking on the wealthy, these movements were only attempts to more equally distribute the loot and privileges of Empire among its citizens. That's why the oppressed colonial subjects of the Empire had no place in these movements.

The line between oppressors and oppressed was unmistakeably drawn. Afrikan and Indian alike opposed this “Jacksonian Democracy”. The English visitor Edward Abdy remarked that he "never knew a man of color that was not an anti-Jackson man.(18) On their side, the white workingmen of the 1830's knowingly embraced the architects of genocide as their heroes and leaders. Far from joining the democratic struggles around the rights of the oppressed, the white workers were firmly committed to crushing them.

Even as they were gradually being pressed downward by the emerging juggernaut of industrial capitalism - faced with wage cuts, increasing speed-up of machine-powered production, individual craft production disappearing in the regimented workshop, etc. - those Euro-Amerikan workers saw their hope for salvation in non-proletarian special privileges and a desperate clinging to petit-bourgeois status. At a time when the brute labor of the Empire primarily rested on the backs of the unpaid, captured Afrikan proletariat, the white workers of the 1830's were only concerned with winning the Ten-Hour Day for themselves. In the 1840's as the Empire annexed the Northern 40% of Mexico and by savage invasion reduced truncated Mexico to a semi-colony, the only issue to the white workingmen's movement was how large would their share of the looting be? It is one thing to be bribed by the bourgeoisie, and still another to demand, organize, argue and beg to be bribed.

The dominant political slogan of the white workers movement of the 1840's was "Vote Yourself A Farm". This expressed the widespread view that it was each settler's right to have cheap land to farm, and that the ideal lifestyle was the old colonial-era model of the self-employed craftsmen who also possessed the security of being part-time farmers. The white labor movement, most particularly the influential newspaper, Working Man's Advocate of New York, called for new legislation under which the Empire would guarantee cheap tracts of Indian and Mexican land to all European settlers (and impoverished workmen in particular).*(19) [* The Homestead Act of 1851 was one result of this campaign.] The white workers literally demanded their traditional settler right to be petit-bourgeois-"little bourgeois", petty imitators who would annex their small, individual plots each time the real bourgeoisie annexed another oppressed nation. It should be clear that the backwardness of white labor is not a matter of "racism", of "mistaken ideas", of "being tricked by the capitalists" (all idealistic instead of materialist formulations); rather, it is a class question and a national question.

This stratum came into being with its feet on top of the proletariat and its head straining up into the petit-bourgeoisie. It's startling how narrow and petty its concerns were in an age when the destiny of peoples and nations was being decided, when the settler Empire was trying to take into its hands the power to decree death to whole nations. We keep coming back to genocide, the inescapable center of settler politics in the 19th Century. So to fully grasp the politics of emerging white labor, we must penetrate to the connection between their class viewpoint and genocide.

By 1840 most of the Indian nations of the East had been swept away, slaughtered or relocated. By 1850 the Empire had consolidated its grip on the Pacific Coast overrunning and occupying Northern Mexico. The Empire had succeeded in bringing the continent under its control. These victories produced that famous "opportunity" that the new waves of European immigrants were coming for. But these changes also brought to a nodal point the contradictions within the fragmented settler bourgeoisie, between planter and mercantile/industrial capital - contradictions which were reflected in all facets of settler society. The tremendous economic expansion of the conquests was a catalyst.

The ripping open of the "New South" to extend the plantation system meant a great rise of Afrikan slaves on the Western frontier. These new cotton areas became primarily Afrikan in population. And the ambitious planter bourgeoisie started seeding slave labor enterprises far outward, as tentacles of the "Slave Power". So at a salt mine in Illinois, a gold mine in California, a plantation in Missouri, aggressive planters appeared with their "moveable factories" of Afrikan slaves. Southern adventurers even briefly seized Nicaragua in 1856 in a premature attempt to annex all of Central Amerika to the "Slave Power".

If the clearing away of the Indian nations had unlocked the door to the spread of the slave system, so too it had given an opportunity to the settler opponents of the planters. And their vision was not of a reborn Greek slaveocracy, but of a brand-new European empire, relentlessly modern, constructed to the most advanced bourgeois principles with the resources of an entire continent united under its command. This new Empire would not only dwarf any power in Old Europe in size, but would be secured through the power of a vast, occupying army of millions of loyal settlers. This bourgeois vision could hardly be considered crackpot, since 20th Century Amerika is in large part the realization of it, but the vision was of an all-European Amerika, an all-white continent.

We can only understand the deep passions of the slavery dispute, the flaring gunfights in Missouri and "Bloody Kansas" between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, and lastly the grinding, monumental Civil War of 1861-1865, as the final play of this greatest contradiction in the settler ranks. It was not freedom for Afrikans that motivated them. No, the reverse. It was their own futures, their own fortunes. Gov. Morton of Ohio called on his fellows to realize their true interests: "We are all personally interested in this question, not indirectly and remotely as in a mere political abstraction - but directly, pecuniarily, and selfishly. If we do not exclude slavery from the Territories, it will exclude us."

To millions of Euro-Amerikans in the North, the slave system had to be halted because it filled the land with masses of Afrikans instead of masses of settlers. To be precise: In the 19th Century a consensus emerged among the majority of Euro-Amerikans that just as the Indian nations before them, the dangerous Afrikan colony had to be at first contained and then totally eliminated, so that the land could be filled by the loyal settler citizens of the Empire.

This was a strategic view endorsed by the majority of Euro-Amerikans. It was an explicit vision that required genocide. How natural for a new Empire of conquerors believing that they had, like gods, totally removed from the earth one family of oppressed nations, to think nothing of wiping out another. the start was to confine Afrikans to the South, to drive them out of the "Free" states in the North. Indeed, in the political language of 19th Century settler politics, the word "Free" also served as a codephrase that meant "non-Afrikan."

The movement to confine Afrikans to the Slave South took both governmental and popular forms. Four frontier states - Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Oregon - passed "immigration" clauses in their constitutions which barred Afrikans as "aliens" from entering the state.(20) It's interesting that the concept of Afrikans as foreign "immigrants" - a concept which tacitly admits separate Afrikan nationality - keeps coming to the surface over and over. Legal measures to force Afrikans out by denying them the vote, the right to own land, use public facilities, practice many professions and crafts, etc. were passed in many areas of the North at the urging of the white mobs. White labor not only refused to defend the democratic rights of Afrikans, but played a major role in these new assaults.

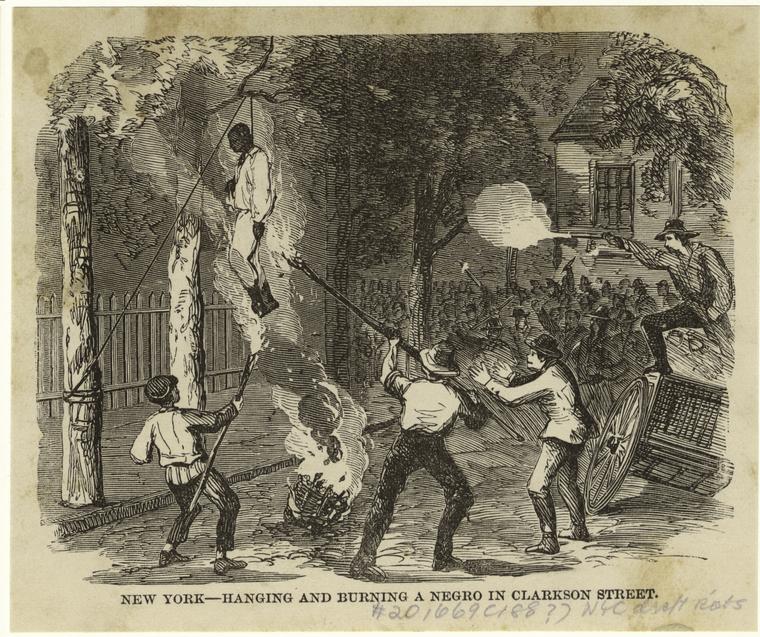

A lynching during the Draft Riots in New York (source)

Periodic waves of mass terror also were used everywhere against Afrikan communities in the North. The Abolitionist press records 209 violent mob attacks in the North between 1830-1849. These violent assaults were not the uncontrolled outpouring of blind racism, as often suggested. Rather, they were carefully organized offensives to achieve definite goals. These mobs were usually led by members of the local ruling class (merchants, judges, military officers, bankers, etc.), and made up of settlers from all strata of society.(21) The three most common goals were: 1) To reverse some local advance in Afrikan organization, education or employment 2) To destroy the local Abolitionist movement 3) To reduce the Afrikan population. In almost every case the mobs, representing both the local ruling class and popular settler opinion, were successful. In almost no cases did any significant number of Euro-Amerikans interfere with the mobs, save to "restore order" or to nobly protect a few lives after the violence had gained its ends.

But to most settlers in the North these attacks were just temporary measures. To them the heart of the matter was the slave system. They thought that without the powerful self-interest of the planters to "protect" Afrikans, that Afrikans as a whole would swiftly vanish from this continent. Today it may sound fantastic that those 19th Century Euro-Amerikans expected to totally wipe out the Afrikan population. Back then it was taken as gospel truth by most settlers that in a "Free" society, where Afrikans would be faced with "competition" (their phrases) from whites, they as inferiors must perish. The comparison was usually made to the Indians - who "died out" as white farmers took their land, as whole villages were wiped out in unprovoked massacres, as hunger and disease overtook them, as they became debilitated with addiction to alcohol, as the survivors were simply driven off to concentration camps at gunpoint. Weren't free Afrikans losing their jobs already? And weren't there literally millions of new European farmers eager to take the farmland that Afrikans had lived on and developed?

Nor was it just the right-wingers that looked forward to getting rid of "The Negro Problem" (as all whites referred to it). All tendencies of the Abolitionists contained not only those who defended the human rights of Afrikans, but also those who publicly or privately agreed that Afrikans must go. Gamaliel Bailey, editor of the major abolitionist journal National Era, promised his white readers that after slavery was ended all Afrikans would leave the U.S. The North's most prominent theologian, Rev. Horace Bushnell, wrote in 1839 that emancipation would be "one bright spot" to console Afrikans, who were "doomed to spin their brutish existence downward into extinction..." That extinction, he told his followers, was only Divine Will, and all for the good. Rev. Theodore Parker was one of the leading spokesmen of radical abolitionism, one who helped finance John Brown's uprising at Harper's Ferry, and who afterwards defended him from the pulpit. Yet even Parker believed in an all-white Amerika; he firmly believed that: "The strong replaces the weak. Thus, the white man kills out the red man and the black man. When slavery is abolished the African population will decline in the United States, and die out of the South as out of Northampton and Lexington."(22)

While many settlers tried to hide their genocidal longings behind the fictions of "natural law" or "Divine Will", others were more honest in saying that it would happen because Euro-Amerikans were determined to make it happen. Thus, even during the Civil War, the House of Representatives issued a report on emancipation that strongly declared: "...the highest interests of the white race, whether Anglo-Saxon, Celt, or Scandinavian, require that the whole country should be held and occupied by these races alone." In other words, they saw no contradiction between emancipation and genocide. The leading economist George M. Weston wrote in 1857 that: "When the white artisans and farmers want the room which the African occupies, they will not take it by rude force, but by gentle and gradual and peaceful processes. The Negro will disappear, perhaps to regions more congenial to him, perhaps to regions where his labor can be more useful, perhaps by some process of colonization we may yet devise; but at all events he will disappear."(23)

National political movements were formed by settlers to bring this day about. The Colonization movement, embodied in the American Colonization Society, organized hundreds of local chapters to press for national legislation whereby Afrikans would be removed to new colonies in Afrika, the West Indies or Central America. U.S. Presidents from Monroe in 1817 to Lincoln in 1860 endorsed the society, and the semi-colony of Liberia was started as a trial. Much larger was the Free Soil Party, which fought to reserve the new territories and states of the West for Europeans only. This was the main forerunner of the Republican party of 1854, the first settler political party whose platform was the defeat of the "Slave Power".

The Republican Party itself strongly reflected this ideology of an all-White Amerika. Although most of its leaders supported limited civil rights for Afrikans, they did so only in the context of the temporary need for Empire to treat its subjects humanely. Sen. William Seward of New York was the leading Republican spokesman before the Civil War (during which he served as Lincoln's Secretary of State). In his famous Detroit speech during the 1860 campaign, he said: "The great fact is now fully realized that the African race here is a foreign and feeble element, like the Indian incapable of assimilation..." Both would, he promised his fellow settlers, "altogether disappear." Lincoln himself said over and over again during his entire political career that all Afrikans would eventually have to disappear from North America. The theme of Afrikan genocide runs like a dark thread, now hidden and now visible in the violent weaving of the future, throughout settler political thought of that day.

It should be remembered that while most Northern settlers opposed Afrikan slavery for these reasons by the 1860's, even after the Civil War settlers promoted Indian, Mexicano and Chinese enslavement when it was useful to colonize the Southwest and West. One settler account of the Apache-U.S. wars in the Southwest reveals the use of slavery as a tool of genocide:

More than anything else, it was probably the incessant kidnapping and enslavement of their women and children that gave Apaches their mad-dog enmity toward the whites...It was officially estimated that 2,000 Indian slaves were held by the white people of New Mexico and Arizona in 1866, after 20 years of American rule - unofficial estimates placed the figure several times higher...'Get them back for us,' Apaches begged an Army officer in 1871, referring to 29 children just stolen by citizens of Arizona; 'our little boys will grow up slaves, and our little girls, as soon as they are large enough, will be diseased prostitutes, to get money for whoever owns them...' Prostitution of captured Apache girls, of which much mention is made in the 1860's and 1870's, seemed to trouble the Apaches exceedingly.(24)

So that at the same time that the U.S. was supposedly ending slavery and "Emancipating" Afrikans, the U.S. Empire was using slavery of the most barbaric kind in order to genocidally destroy the Apache. It was colonial rule and genocide that were primary.

The great democratic issues of that time could only grow out of this intense, seething nexus of Empire and colony, of oppressor nation and oppressed nations. Nothing took place that was not a factor on the battleground of Empire and oppressed. Nothing. Everyone was caught up in the war, however dimly they understood their own position. The new millions of immigrant European workers were desperately needed by the Empire. By 1860 half of the populations of New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh and St. Louis were new immigrant Europeans. These rein forcements were immediately useful in new offensives against the Indian, Afrikan and Mexicano peoples. While the settler economy was still absolutely dependent upon the forced labor of the Afrikan proletariat (cotton alone accounted for almost 60% of U.S. export earnings in 1860), the new reinforcements provided the means to reverse the dangerous concentrations of Afrikans in the metropolitan centers.

Frederick Douglass said in 1855: "Every hour sees us elbowed out of some employment to make room perhaps for some newly arrived immigrants, whose hunger and color are thought to give them a title to especial favor. White men are becoming house-servants, cooks and stewarts, common laborers and flunkeys to our gentry..." The Philadelphia newspaper Colored American said as early as 1838 that free Afrikans "have ceased to be hackney coachmen and draymen*, and they are now almost displaced as stevedores. [*carriers — those who hauled goods around the city for a fee] They are rapidly losing their places as barbers and servants." In New York City Afrikans were the majority of the house-servants in 1830, but by 1850 Irish house-servants outnumbered the entire Afrikan population there.(25) The Empire was swiftly moving to replace the rebellious and dangerous Afrikan proletariat by more submissive and loyal Europeans.

Even in the Deep South, urban Afrikan proletarians were increasingly replaced by loyal European im migrants. In New Orleans the draymen were all Afrikan in 1830, but by 1840 were all Irish.(26) One historian points out: "Occupational exclusion of Blacks actually began before the Civil War. In an unpublished study, Weinbaum has demonstrated conclusively such exclusion and decline (of skilled Afrikan workers - ed.) for Rochester, New York, Blacks between 1840 and 1860. My own work shows a similar decline in Charleston, S.C., between 1850 and 1860. And these trends continued in Southern cities during Reconstruction. A crucial story has yet to be told. The 1870 New Orleans city directory, Woodward pointed out, listed 3,460 Black carpenters, cigarmakers, painters, shoemakers, coopers, tailors, blacksmiths, and foundry hands. By 1904, less than 10 per cent of that number appeared even though the New Orleans population had increased by more than 50 per cent."(27) Beneath the great events of the Civil War and Reconstruction, the genocidal restructuring of the oppressed Afrikan nation continued year after year.

This was clearly the work of the capitalists. But where did the new stratum of Euro-Amerikan workers stand on this issue? The defeat of the Slaveocracy, the political upheavals of the great conflict, and the enormous expansion of European immigration had stirred and heartened white labor. In both North and South local unions revived and new unions began. New attempts emerged to form effective national federations of all white workers. Between 1863-73 some 130 white labor newspapers began publication.(28) The Eight Hour Day movement "ran with express speed" from coast to coast in the wake of the war. During the long and bitter Depression of 1873-78, militant struggles broke out, ending in the famous General Strike of 1877. In this last strike the white workers won over to their side the troops sent by the government or defeated them in bloody street fighting in city after city. White labor in its rising cast a long shadow over the endless banquet table of the bourgeoisie.

Truly, white labor had become a giant in size. Even in a Deep South state such as Louisiana, by the 1860 census white laborers made up one-third of the total settler population.(29) In St. Louis (then the third-largest manufacturing center in the Empire) the 1864 census showed that slightly over one-third of that city's 76,000 white men were workers (rivermen, factory laborers, stevedores, etc.). In the Boston of the 1870's fully one-half of the total white population were workers and their families, mostly Irish.(30) In some Northern factory towns the proportion was even higher.

The ideological head on this giant body, however, still bore the cramped, little features of the old artisan/farmer mentality of previous generations. When this giant was aroused by the capitalists' cuts and kicks, its angry flailings knocked over troops and sent shockwaves of fear and uncertainty spreading through settler society. But its petit-bourgeois confusions let the capitalists easily outmaneuver it, each time herding it back to resentful acquiescence with skillful applications of "the carrot and the stick".

What was the essence of the ideology of white labor? Petit-bourgeois annexationism. Lenin pointed out in the great debates on the National Question that the heart of national oppression is annexation of the territory of the oppressed nation(s) by the oppressor nation. There is nothing abstract or mystical about this. To this new layer of European labor was denied the gross privileges of the settler bourgeoisie, who annexed whole nations. Even the particular privileges that so comforted the earlier Euro-Amerikan farmers and artisans - most particularly that of "annexing" individual plots of land every time their Empire advanced - were denied these European wage-slaves. But, typically, their petit-bourgeois vision saw for themselves a special, better kind of wage-slavery. The ideology of white labor held that as loyal citizens of the Empire even wage-slaves had a right to special privileges (such as "white man's wages"), beginning with the right to monopolize the labor market.

We must cut sharply through the liberal camouflage concealing this question. It is insufficient - and therefore misleading - to say that European workers wished to "discriminate against" or "exclude" or were "prejudiced against" colored workers. It was the labor of Afrikan and Indian workers that created the economy of the original Amerika; likewise, the economy of the Southwest was distilled from the toil of the Indian/Mexicano workers, and that of Northern California and the Pacific Northwest was built by Mexicano and Chinese labor. Immigrant European workers proposed to enter an economy they hadn't built, and 'annex', so as to speak, the jobs that the nationally oppressed had created.

Naturally, the revisionists always want to talk about it as a matter of white workers not sharing equally enough - as though when a robber enters your home and takes everything you've earned, the problem is that this thief should "share" your property better! Since the ideology of white labor was annexationist and predatory, it was of necessity also rabidly pro-Empire and, despite angry outbursts, fundamentally servile towards the bourgeoisie. It was not a proletarian outlook, but the degraded outlook of a would-be labor aristocracy.

We can grasp this very concretely actually investigating the political rising of European labor in that period in relation to the nationally oppressed. Even today few comrades know how completely the establishment of the Empire in the Pacific Northwest depended upon Chinese labor.* [*As well as the later waves of Japanese, Filipino and Korean workers.] In fact, the Chinese predate the Amerikan settler presence on the West Coast by many years.(31) When the famous Lewis & Clark expedition sent out by President Jefferson reached the Pacific in 1804, they arrived some sixteen years after the British established a major shipyard on Vancouver Bay - a shipyard manned by Chinese shipwrights and sailors.

For that matter, the Spanish further South in California had even earlier imported skilled Chinese workers. We know that Chinese had been present at the founding of Los Angeles in 1781. This is easy to understand when we see that California was closer to Asia than New York in practical terms; in travel time San Francisco was but 60 days sail from Canton - but six months by wagon train from Kansas City.

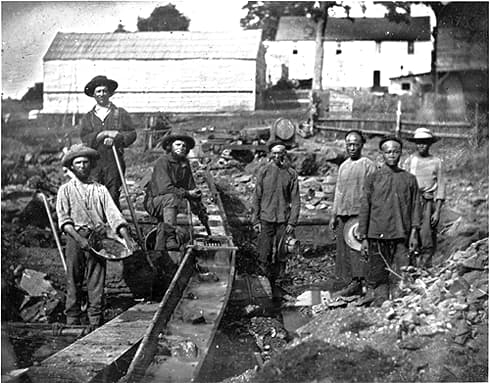

Chinese fishermen in Monterey, CA in 1875. (source)

The settler capitalists used Chinese labor to found virtually every aspect of their new Amerikan economy in this region. The Mexicano people, who were an outright majority in the area, couldn't be used because the settlers were engaged in reducing their numbers so as to consolidate U.S. colonial conquest. During the 1830's, '40s and '50s the all-too-familiar settler campaign of mass terror, assassination, and land-grabbing was used against the Mexicanos. Rodolfo Acuna summarizes: "During this time, the Chinese were used as an alternative to the Chicanos as California's labor force. Chicanos were pushed to the southern half of the state and were literally forced out of California in order to escape the lynching, abuses, and colonized status to which they had been condemned."(32) Thus, the Chinese were not only victims of Amerika, but their very presence was a part of genocidal campaign to dismember and colonize the Mexican Nation. In the same way, decades later Mexicano labor - now driven from the land and reduced to colonial status - would be used to replace Chinese labor by the settlers.

The full extent of Chinese labor's role is revealing. The California textile mills were originally 70-80% Chinese, as were the garment factories. As late as 1880, Chinese made up 52% of all shoe makers and 44% of all brick makers in the state, as well as one-half of all factory workers in the city of San Francisco.(33) The fish canneries were so heavily manned by Chinese - over 80% - that when a mechanical fish cleaner was introduced it was popularly called "the Iron Chink". The fish itself (salmon, squid, shrimp, etc.) was often caught and brought in by Chinese fishermen, who pioneered the fishing industry in the area. Chinese junks were then a common sight in California harbors, and literally thousands of Chinese seamen lived in the numerous all-Chinese fishing villages that dotted the coast from San Diego up to Oregon. As late as 1888 there were over 20 Chinese fishing villages just in San Francisco and San Pablo Bays, while 50% of the California fishing industry was still Chinese. Farms and vineyards were also founded on Chinese labor: in the 1870's when California became the largest wheat growing state in the U.S. over 85% of the farm labor was Chinese.

Chinese workers played a large part as well in bringing out the vast mineral wealth that so accelerated the growth of the U.S. in the West. In 1870 Chinese made up 25% of all miners in California, 21% in Washington, 58% in Idaho, and 61% in Oregon. In California the special monthly tax paid by each Chinese miner virtually supported local government for many years - accounting for 25-50% of all settler government revenues for 1851-70. Throughout the area Chinese also made up a service population, like Afrikans and Mexicanos in other regions of the Empire, for the settlers. Chinese cooks, laundrymen, and domestic servants were such a common part of Western settler life in the mines, cattle ranches and cities that no Hollywood "Western" movie is complete without its stereotype Chinese cook.

White and Chinese miners hoping to strike it rich during the California Gold Rush at Auburn Ravine in 1852. (source)

But their greatest single feat in building the economy of the West was also their undoing. Between 1865 and 1869 some 15,000 Chinese borers carved the far Western stretch of the Transcontinental rail line out of the hostile Sierra and Rocky Mountain ranges. Through severe weather they cut railbeds out of rock mountainsides, blasted tunnels, and laid the tracks of the Central Pacific Railroad some 1,800 miles East to Ogden, Utah. It was and is a historic engineering achievement, every mile paid for in blood of the Chinese who died from exposure and avalanches. The reputation earned by Chinese workers led them to be hired to build rail lines not only in the West, but in the Midwest and South as well. This Transcontinental rail link enabled the minerals and farm produce of the West to be swiftly shipped back East, while giving Eastern industry ready access to Pacific markets, not only of the West Coast but all of Asia via the port of San Francisco.

The time-distance across the continent was now cut to two weeks, and cheap railroad tickets brought a flood of European workers to the West. There was, of course, an established settler traditon of terrorism towards Chinese. The Shasta Republican complained in its Dec. 12, 1856 issue that: "Hundreds of Chinamen have been slaughtered in cold blood in the last 5 years...the murder of Chinamen was of almost daily occurrence." Now the new legions of immigrant European workers demanded a qualitative increase in the terroristic assaults, and the 1870's and 1880's were decades of mass bloodshed.

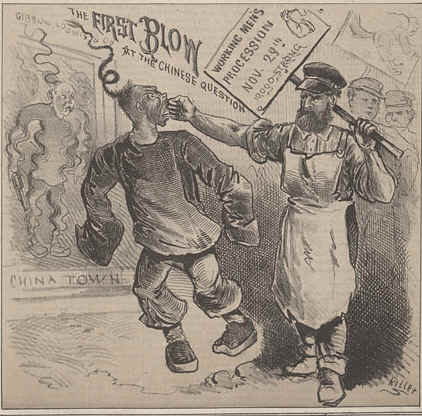

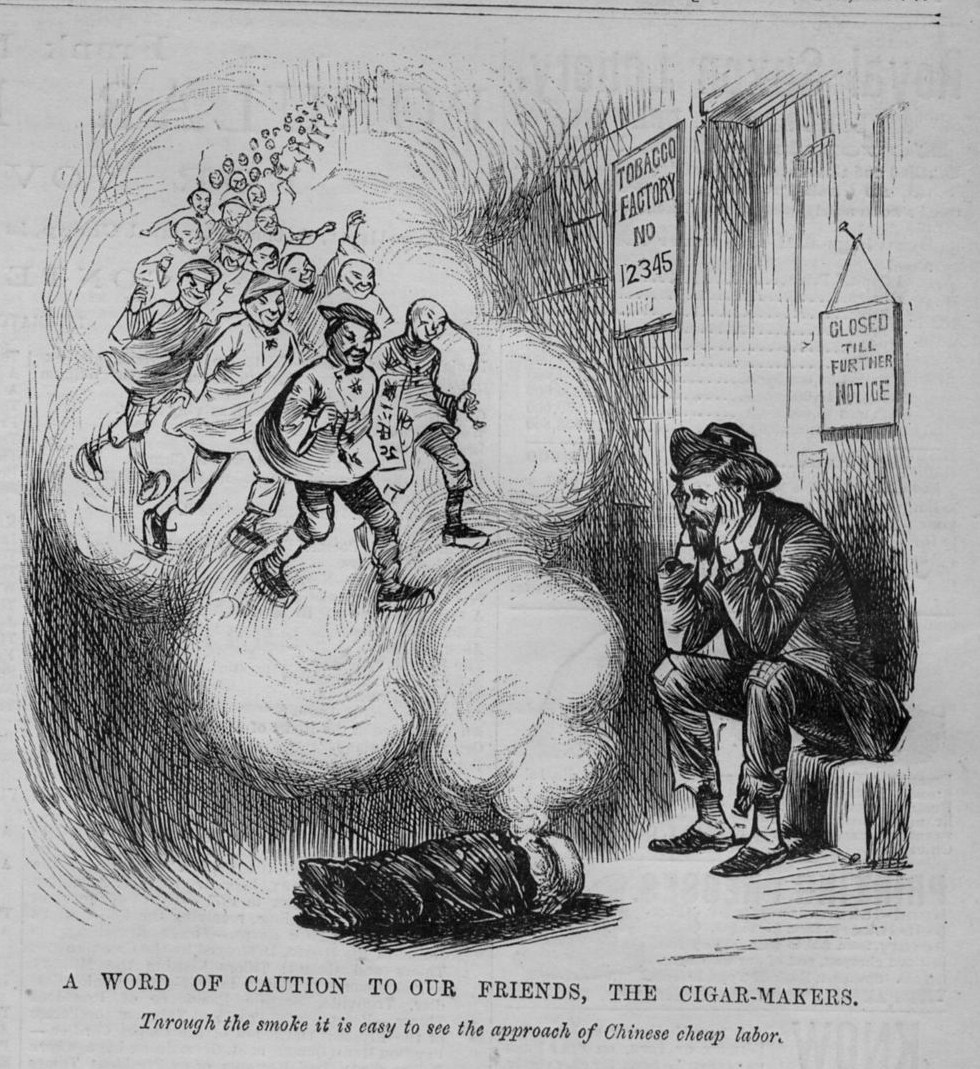

"The First Blow to the Chinese Question" From The Wasp v.2, August 1877- July 1878. (source)

The issue was very clear-cut - jobs. By 1870, some 42% of the whites in California were European immigrants. With their dreams of finding gold boulders lying in the streams having faded before reality, these new crowds of Europeans demanded the jobs that Chinese labor had created.(34) More than demanded, they were determined to "annex", to seize by force of conquest, all that Chinese workers had in the West. In imitation of the bourgeoisie they went about plundering with bullets and fire. In mining camps and towns from Colorado to Washington, Chinese communities came under attack. Many Chinese were shot down, beaten, their homes and stores set afire and gutted. In Los Angeles Chinese were burned alive by the European vigilantes, who also shot and tortured many others.

In perverse fashion, the traditional weapons of trade unionism were turned against the Chinese workers in this struggle. Many manufacturers who employed Chinese were warned that henceforth all desirable jobs must be filled by European immigrants. Boycotts were threatened, and in some industries (such as wineries and cigar factories) the new white unions invented the now-famous "union label" - printed tags which guaranteed that the specific product was produced solely by European unions. In 1884, when one San Francisco cigar manufacturer began replacing Chinese workers (who then made up 80-85% of the industry there) with European immigrants, the Chinese cigarmakers went on strike. Swiftly, the San Francisco white labor movement united to help the capitalists break the strike. Scabbing was praised, and the Knights of Labor and other European workers' organizations led a successful boycott of all cigar companies that employed Chinese workers. Boycotts were widely used in industry after industry to seize Chinese jobs.(35)

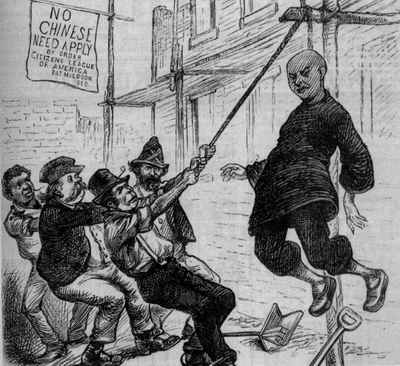

1877 engraving of anti-Chinese cartoon from Frank Leslie's Illustrated.

In the political arena a multitude of "Anti-Coolie" laws were passed on all levels of settler government. Special taxes and "license fees" on Chinese workers and tradesmen were used both to discourage them and to support settler government at their expense. Chinese who carried laundry deliveries on their backs in San Francisco had to pay the city a sixty-dollar "license fee" each year.(36) Many municipalities passed laws ordering all Chinese to leave, enforced by the trade union mobs.

The decisive point of the Empire-wide campaign to plunder what the Chinese had built up in the West was the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Both Democratic and Republican parties supported this bill, which barred all Chinese immigration into the U.S. and made Chinese ineligible for citizenship. The encouragement offered by the capitalist state to the anti-Chinese offensive shows the forces at work. In their frenzy of petty plundering, European labor was being permitted to do the dirty work of the bourgeoisie. The Empire needed to promote and support this flood of European reinforcements to help take hold of the newly conquered territories. As California Gov. Henry Haight (whose name lives on in a certain San Francisco neighborhood) said in 1868: "No man is worthy of the name of patriot or statesman who countenances a policy which is opposed to the interests of the free white laboring and industrial classes...What we desire for the permanent benefit of California is a population of white men...We ought not to desire an effete population of Asiatics..." The national bourgeoisie used the "Anti-Coolie" movement and the resulting legislation to force individual capitalists to follow Empire policy and discharge Chinese in favor of Europeans. Now that the Chinese had built the economy of the Pacific Northwest, it was time for them to be stripped and driven out.

The passage of the 1882 Act was taken as a "green-light", a "go-ahead" signal of approval to immigrant European labor from Congress, the White House and the majority of Euro-Amerikans. It was taken as a license to kill, a declaration of open looting season on Chinese. Terrance Powderly, head of the Knights of Labor (which boasted that it had recruited Afrikan workers to help European labor) praised the victory of the Exclusion Act by saying that now the task for trade unionists was to finish the job - by eliminating all Chinese left in the U.S within the year!(36)

The settler propaganda kept emphasizing how pure, honest Europeans had no choice but "defend" themselves against the dark plots of the Chinese. Wanting to seize ("annex") Chinese jobs and small businesses, European immigrants kept shouting that they were only "defending" themselves against the vicious Chinese who were trying to steal the white man's jobs! And in case any European worker had second thoughts about the coming lynch mob, a constant ideological bombardment surrounded him by trade union and "socialist" leaders, bourgeois journalists, university professors and religious figures, politicians of all parties, and so on. Having decided to "annex" the fruits of the Chinese development of the Northwest, the usual settler propaganda about "defending" themselves was put forth.

Nor was Euro-Amerikan racial-sexual hate propaganda neglected, just as bizarre and perverted as it is about Afrikans. In 1876, for example, the New York Times published an alleged true interview with the Chinese operator of a local opium den. The story has the reporter asking the "Chinaman" about the "handsome but squalidly dressed young white girl" he sees in the opium den. The "Chinaman" allegedly answers: "Oh, hard time in New York. Young girl hungry. Plenty come here. Chinaman always have something to eat, and he like young white girl, He! He!"* [*Similar "news" stories are very popular today, reminding the white masses about all the runaway white teenagers who become "captives" of Afrikan "pimps and dope dealers". When we see such themes being pushed in the bourgeois media, we should know what's behind it.] A woman's magazine warned their readers to never leave little white girls alone with Chinese servants. The settler public was solemnly alerted that the Chinese plot was to steal white workers' jobs and thus force the starving wives to become their concubines. The most telling sign of the decision to destroy the Chinese community was the settler realization that these Chinese looked just like Afrikans in "women's garments"!

The ten years after the passage of the Exclusion Act saw the successful annexation of the Chinese economy on the West Coast. Tacoma and Seattle forced out their entire Chinese populations at gunpoint. In 1885 the infamous Rock Springs, Wyoming massacre took place, where over 20 Chinese miners were killed by a storm of rifle-fire as European miners enforced their take-over of all mining. Similar events happened all over the West. In 1886 some 35 California towns reported that they had totally eliminated their Chinese populations.

On the coast Italian immigrants burned Chinese ships and villages to take over most of the fishing industry by 1890. By that same year most of the Chinese workers in the vineyards had been replaced by Europeans. By 1894 the bulk of Chinese labor on the wheat and vegetable farms had been forced out. Step by step, as fast as they could be replaced, the Chinese who once built the foundation of the region's economy were being driven out.

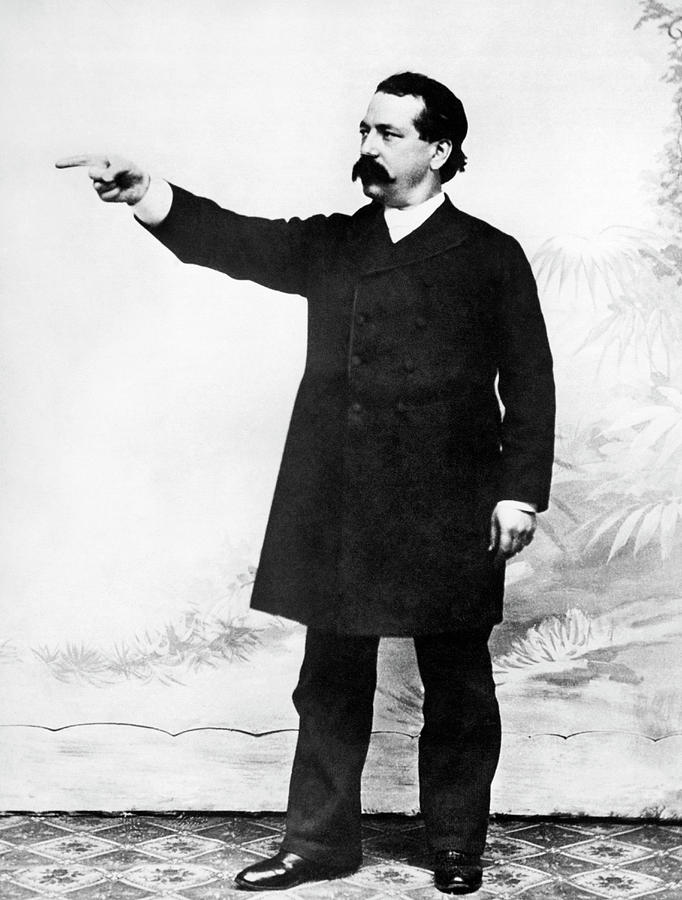

Who took part in this infamous campaign? Virtually the whole of the Euro-Amerikan labor movement in the U.S., including "socialists" and "Marxists". Both of the two great nationwide union federations of the 19th Century, the National Labor Union and the later Knights of Labor, played an active role.(37) The Socialist Labor Party was involved. The leading independent white labor newspaper, the Workingman's Advocate of Chicago, was edited by A. C. Cameron. He was a leader of the National Labor Union, a respected printing trades unionist, and the delegate from the N.L.U. to the 1869 Switzerland con- ference of the Communist First International. His paper regularly printed speeches and theoretical articles by Karl Marx and other European Communists. Yet he loudly called in his newspaper for attacks on the immigrant "Chinamen, Japanese, Malays, and Monkeys" from Asia. Even most "Marxists" who deplored the crude violence of the labor mobs, such as Adolph Doubai (one of the leading German Communist immigrants), agreed that the Chinese had to be removed from the U.S.(38) It is easy to predict that if even European "Marxists" were so strongly pulled along by the lynch mobs, the bourgeois trade union leaders had to be running like dogs at the head of the hunt. Andrew Furuseth, the founder of the Seafarers Internation Union, AFL-CIO, Pat McCarthy, leader of the San Francisco Building Trades Council, Sam Gompers, leader of the cigarmakers union and later founder of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), were just a few of the many who openly led and incited the settler terror.(39)

Samuel Gompers (source)

When we say that the petit-bourgeois consciousness of European immigrant labor showed that it was a degraded stratum seeking extra-proletarian privileges, we aren't talking about a few nickels and dimes; the issue was genocide, carrying out the dirty work of the capitalists in order to reap some of the bloody fruits of national oppression. It is significant that the organizational focus of the early anti-Chinese campaign was the so-called Working Men's Party of California, which was organized by an Irish immigrant confidence-man named Dennis Kearney. Kearney was the usual corrupt, phrase-making demagogue that the white masses love so well ("I am the voice of the people. I am the dictator...I owe the people nothing, but they owe me a great deal.")* [*Unfortunately, we have Kearneys of our own.]

This sleazy party, built on the platform of wiping out Chinese labor and federal reforms to aid white workers and farmers, attracted thousands of European workers - including most of the European "socialists" in California. Before falling apart from corruption, thugism and factionism, Kearney's party captured seats in the State Assembly, the mayoralty in Sacramento, and controlled the Constitutional Convention which reformed the California Constitution. Even today settler historians, while deploring Kearney's racism, speak respectfully of the party's role in liberal reforms! Even revisionist CPUSA historians apparently feel no shame in praising this gang of degnerates for "arousing public support for a number of important labor demands...forcing old established parties to listen more attentively to the demands of the common people."(40) What this shows is that if the "respectable" Euro-Amerikan trade-unionists and "Marxists" were scrabbling on their knees before the bourgeoisie along with known criminals such as Kearney, then they must have had much in common (is it so different today?).

The monopoly on desirable jobs that European labor had won in the West was continually "defended" by new white supremacist assaults. The campaign against Chinese was continued long into the 20th century, particularly so that its momentum could be used against Japanese, Filipino and other Asian immigrant labor. The AFL played a major role in this. Gompers himself, a Jewish immigrant who became the most powerful bourgeois labor leader in the U.S., co-authored in 1902 a mass-distributed racist tract entitled: Some Reasons For Chinese Exclusion: Meat vs. Rice, American Manhood vs. Asiatic Coolieism - Which Shall Survive? In this crudely racist propaganda, the respected AFL President comforted white workers by pointing out that their cowardly violence toward Asians was justified by the victim's immoral and dangerous character: "The Yellow Man found it natural to lie, cheat and murder". Further, he suggested, in attacking Asian workers, whites were just nobly protecting their own white children, "thousands" of whom were supposed to be opium-addicted "prisoners" kept in the unseen back rooms of neighborhood Chinese laundries: "What other crimes were committed in those dark, fetid places, when those little innocent victims of the Chinamen's wiles were under the influence of the drug are too horrible to imagine..."(41) What's really hard "to imagine" is how anyone could believe this fantastical porno-propaganda; in truth, settlers will eagerly swallow any falsehoods that seem to justify their continuing crimes against the oppressed.

The Empire-wide campaign against the Chinese national minority played a major role in the history of Euro-Amerikan labor; it was a central rallying issue for many, a point around which immigrant European workers and other settlers cound unite. It was a campaign in which all the major Euro-Amerikan labor federations, trade unions and "socialist" organizations joined together. The annexation of the Chinese economy of the West during the later half of the 19th Century was but another expression of the same intrusion that Afrikans met in the South and North. All over the Empire immigrant European labor was being sent against the oppressed, to take what little we had.

At times even their bourgeois masters wished that their dogs were on a shorter leash. Many capitalists saw, even as we were being cut down, that it would be useful to preserve us as a colonial labor force to be exploited whenever needed; but the immigrant white worker had no use for us whatsoever. Therefore, in the altered geometry of forces within the Empire, the new Euro-Amerikan working masses became willing pawns of the most vicious elements in the settler bourgeoisie, seeing only advantages in every possibility of our genocidal disappearance. And in this scramble upwards those wretched immigrants shed, like an old suit of clothes, the proletarian identity and honor of their Old European past. Now they were true Amerikans, real settlers who had done their share of the killing, annexing and looting.

If Euro-Amerikan labor's attitude towards Chinese labor was straightforward and brutal, towards the Afrikan colony it was more complex, more tactical. Indeed, the same Euro-Amerikan labor leaders who sponsored the murderous assaults on Chinese workers kept telling Afrikan workers how "the unity of labor" was the first thing in their hearts!

Terrance Powderly, the Grand Master Workman of the Knights of Labor (who had personally called for wiping out all Chinese in North America within one year), suddenly became the apostle of brotherhood when it came to persuading Afrikans to support his organization: "The color of a candidate shall not debar him from admission; rather let the coloring of his mind and heart be the test."(42) This apparent contradiction arose from the unique position of the Afrikan colony. Where the Chinese workers had been a national minority whose numbers at any one time probably never exceeded 100,000 (roughly two-thirds of the Chinese returned to Asia), Afrikans were an entire colonized Nation; on their National Territory in the South they numbered some 4 millions. This was an opponent Euro-Amerikan labor had to engage more carefully.

The relationship between Euro-Amerikan labor and Afrikan labor cannot be understood just from the world of the mine and mill. Their relationship was not separate from, but a part of, the general relation of oppressor nation to colonized oppressed nation. And at that time the struggle over the Afrikan colony was the storm center of all politics in the U.S. Empire. The end of the Civil War and the end of chattel Afrikan slavery were not the resolution of bitter struggle in the colonial South, but merely the opening of a whole new stage.

We have to see that there were two wars going on, and that both were mixed in the framework of the Civil War. The first conflict was the fratricidal, intra-settler war between Northern industrial capitalists and Southern planter capitalists. We use the phrase "Civil War" because it is the commonly known name for the war. It is more accurate to point out that the war was between two settler nations for ownership of the Afrikan colony - and ultimately for ownership of the continental Empire. The second was the protracted struggle for liberation by the colonized Afrikan Nation in the South. Neither struggle ended with the military collapse of the Confederacy in 1865. For ten years, a long heartbeat in history, both wars took focus around the Reconstruction governments.

The U.S. Empire faced the problem that its own split into two warring settler nations had provided the long-awaited strategic moment for the anti-colonial rising of the oppressed Afrikan Nation. Just as in the 1776 War of Independence, both capitalist factions in the Civil War hoped that Afrikans would remain docilely on the sidelines while Confederate Amerika and Union Amerika fought it out. But the rising of millions of Afrikans, striking off their chains, became the decisive factor in the Civil War. As DuBois so scathingly points out:

"Freedom for the slave was the logical result of a crazy attempt to wage war in the midst of four million black slaves, and trying the while sublimely to ignore the interests of those slaves in the outcome of the fighting. Yet, these slaves had enormous power in their hands. Simply by stopping work, they could threaten the Confederacy with starvation. By walking into the Federal camps, they showed to doubting Northerners the easy possibilities of using them as workers and as servants, as farmers, and as spies, and finally, as fighting soldiers. And not only using them thus, but by the same gesture depriving their enemies of their use in just these fields. It was the fugitive slave who made the slaveholders face the alternative of surrendering to the North, or to the Negroes."

Judge John C. Underwood of Richmond, Virginia, testified later before Congress that: "I had a conversation with one of the leading men in that city, and he said to me that the enlistment of Negro troops by the United States was the turning point of the rebellion; that it was the heaviest blow they ever received. He remarked that when the Negroes deserted their masters, and showed a general disposition to do so and join the forces of the United States, intelligent men everywhere saw that the matter was ended."(43)

While marching through a region, the black troops would sometimes pause at a plantation, ascertain from the slaves the name of the "meanest" overseer in the neighborhood, and then, if he had not fled, "tie him backward on a horse and force him to accompany them." Although a few masters and overseers were whipped or strung up by a rope in the presence of their slaves, this appears to have been a rare occurrence. More commonly, black soldiers preferred to apportion the contents of the plantation and the Big House among those whose labor had made them possible, singling out the more "notorious" slaveholders and systematically ransacking and demolishing their dwellings. "They gutted his mansion of some of the finest furniture in the world," wrote Chaplain Henry M. Turner, in describing a regimental action in North Carolina. Having been informed of the brutal record of this slaveholder, the soldiers had resolved to pay him a visit. While the owner was forced to look on, they went to work on his "splendid mansion" and "utterly destroyed every thing on the place." Wielding their axes indiscriminately, they shattered his piano and most of the furniture and ripped his expensive carpets to pieces. What they did not destroy they distributed among his slaves. --Leon F. Littwack, Been in the Storm So Long

The U.S. Empire took advantage of this rising against the Slave Power to conquer the Confederacy - but now its occupying Union armies had to not only watch over the still sullen and dangerous Confederates, but had to prevent the Afrikan masses from breaking out. Four millions strong, the Afrikan masses were on the move politically. Unless halted, this rapid march could quickly lead to mass armed insurrection against the Union and the formation of a New Afrikan government in the South. Events had suddenly moved to that point.

The most perceptive settlers understood this very well. The Boston capitalist Elizur Wright said in 1865: "...the blacks must be enfranchised or they will be ready and willing to fight for a government of their own." Note, "a government of their own. " For having broken the back of the Confederacy, having armed and trained themselves contrary to settler expectations, the Afrikan masses were in no mood to passively submit to reenslavement. And they desired and demanded Land, the national foundations that they themselves had created out of the toil of three hundred years. DuBois tells us: "There was continual fear of insurrection in the Black Belt. This vague fear increased toward Christmas, 1866. The Negroes were disappointed because of the delayed division of lands. There was a natural desire to get possession of firearms, and all through the summer and fall, they were acquiring shotguns; muskets, and pistols, in great quantities."

All over their Nation, Afrikans had seized the land that they had sweated on. Literally millions of Afrikans were on strike in the wake of the Confederacy's defeat. The Southern economy - now owned by Northern Capital - was struck dead in its tracks, unable to operate at all against the massive, stony resistance of the Afrikan masses. This was the greatest single labor strike in the entire history of U.S. Empire. It was not done by any AFL-CIO-type official union for higher wages, but was the monumental act of an oppressed people striking out for Land and Liberation. Afrikans refused to leave the lands that were now theirs, refused to work for their former slavemasters.

U.S. General Rufus Saxon, former head of the Freedmen's Bureau in South Carolina, reported to a Congressional committee in 1866 that Afrikan field workers in that state were arming themselves and refusing to "submit quietly" to the return of settler rule. Even the pro-U.S. Afrikan petit-bourgeoisie there, according to Saxon, was afraid they were losing control of the masses: "I will tell you what the leader of the colored Union League...said to me: they said that they feared they could not much longer control the freedmen if I left Charlestown...they feared the freedmen would attempt to take their cause in their own hands."(44)

The U.S. Empire's strategy for reenslaving their Afrikan colony involved two parts: 1. The military repression of the most organized and militant Afrikan communities. 2. Pacifying the Afrikan Nation by neo-colonialism, using elements of the Afrikan petit-bourgeoisie to lead their people into embracing U.S. citizenship as the answer to all problems. Instead of nationhood and liberation, the neo-colonial agents told the masses that their democratic demands coud be met by following the Northern settler capitalists (i.e. the Republican Party) and looking to the Federal Government as the ultimate protector of Afrikan interests.

So all across the Afrikan Nation the occupying Union Army - supposedly the "saviors" and "emancipators" of Afrikans - invaded the most organized, most politically conscious Afrikan communities. In particular, all those communities where the Afrikan masses had seized land in a revolutionary way came under Union Army attack. In those areas the liberation of the land was a collective act, with the workers from many plantations holding meetings and electing leaders to guide the struggle. Armed resistance was the order of the day, and planter attempts to retake the land were rebuffed at rifle point. The U.S. Empire had to both crush and undermine this dangerous development that had come from the grass roots of their colony.

In August, 1865 around Hampton, Virginia, for example, Union cavalry were sent to dislodge 5,000 Afrikans from liberated land. Twenty-one Afrikan leaders were captured, who had been "armed with revolvers, cutlasses, carbines, shotguns." In the Sea Islands off the south Carolina coast some 40,000 Afrikans were forced off the former plantations at bayonet point by Union soldiers. While the Afrikans had coolly told returning planters to go - and pulled out weapons to emphasize their orders - they were not able to overcome the U.S. Army. In 1865 and 1866 the Union occupation disarmed and broke up such dangerous outbreaks. The special danger to the U.S. Empire was that the grass-roots political drive to have armed power over the land, to build economically self-sufficient regions under Afrikan control, would inevitably raise the question of Afrikan sovereignty.

Afrikan soldiers who had learned too much for the U.S. Empire's peace of mind were a special target (of both Union and Confederate alike). Even before the War's end a worried President Lincoln had written to one of his generals: "I can hardly believe that the South and North can live in peace unless we get rid of the Negroes. Certainly they cannot, if we don't get rid of the Negroes whom we have armed and disciplined and who have fought with us, I believe, to the amount of 150,000 men. I believe it would be better to export them all..."

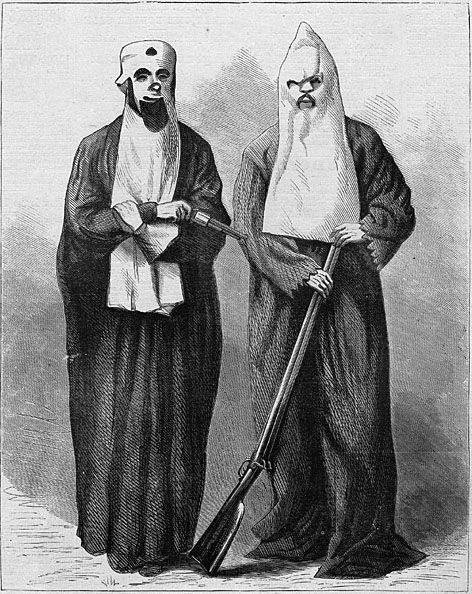

Afrikan U.S. army units were hurriedly disarmed and disbanded, or sent out of the South (out West to serve as colonial troops against the Indians, for example). The U.S. Freedmen's Bureau said in 1866 that the new, secret white terrorist organizations in Mississippi placed a special priority on murdering returning Afrikan veterans of the Union Army. In New Orleans some members of the U.S. 74th Colored Infantry were arrested as "vagrants" the day after they were mustered out of the army. Everywhere in the occupied Afrikan Nation an emphasis was placed on defusing or wiping out the political guerrillas and militia of the Afrikan masses.

The U.S. Empire's second blow was more subtle. The Northern settler bourgeoisie sought to convince Afrikans that they could, and should want to, become citizens of the U.S. Empire. To this end the 14th Amendment to the Constitution involuntarily made all Afrikans here paper U.S. citizens. This neo-colonial strategy offered Afrikan colonial subjects the false democracy of paper citizenship in the Empire that oppressed them and held their Nation under armed occupation.

While the U.S. Empire had regained its most valuable colony, it had major problems. The Union Armies militarily held the territory of the Afrikan Nation. But the settlers who had formerly garrisoned the colony and overseen its economy could no longer be trusted; even after their attempted rival empire had been ended, the Southern settlers remained embittered and dangerous enemies of the U.S. bourgeoisie. The Afrikan masses, whose labor and land provided the wealth that the Empire extracted from their colony, were rebellious and unwilling to peacefully submit to the old ways. The Empire needed a loyalist force to hold and pacify the colony.

The U.S. Empire's solution was to turn their Afrikan colony into a neo-colony. This phase was called Black Reconstruction.* Afrikans were promised democracy, human rights, self-government and popular ownership of the land - but only as loyal "citizens" of the U.S. Empire. Under the neo-colonial leadership of some petit-bourgeois elements, Afrikans became the loyalist social base. Not only were they enfranchised en masse, but Afrikans were participants and leaders in government: Afrikan jurors, judges, state officials, militia captains, Governors, Congressmen and even several Afrikan U.S. Senators were conspicuous.

This regional political role for Afrikans produced results that would be startling in the Empire today, and by the settler standards of a century ago were totally astonishing. The white supremacist propagandist James Pike reports angrily of state government in South Carolina, the state with the largest Afrikan presence in government: