Internationalism has always played a central role in the modern revolutionary struggles for independence and socialism. We cannot go fully into the history of the “national question” here, but we will show how the importance of struggles for national self-determination and independence was emphasized by communists early on the in the 20th Century European experience.

It is necessary to begin our study here, in order to refute two bourgeois political lines that have confusing influence, though of varying degrees, within the Movements in the U.S. Empire. The first is U.S. oppressor nation revisionism. It argues that all “nationalism” is “narrow” and ultimately reactionary. New Afrika is compared to Israel, revolutionary nationalism is said to be like Zionism. These revisionists make “class” holy, and argue that merging the New Afrikan proletariat with the settler masses is the only road to liberation. As a corollary in this Eurocentric view, only the “u.s.a.” is considered to be a “real” nation. Hawaii, the Navaho nation, Puerto Rico, and so on are not thought to be real nations, or in any case are not thought to be very important politically. We can see the widespread effect of this attitude in Third-World comrades who think “ally” only means Euro-Amerikans.

The second bourgeois line believes that liberation for the oppressed nations can only come from developing their own capitalism (Black capitalism, etc.). The apostles of this put down modern class-consciousness as unnecessary, and picture communism or Marxism-Leninism as a “racist European philosophy” whose leaders always ignored the rights of small nations and colonies. These two bourgeois lines keep reinforcing each other back and forth, keep mutually pitting “class” and “nation” against each other, and both support the continued ideological domination of the U.S. oppressor nation over its captive nations and peoples. Modern communism in the imperialist era recognizes the dialectical interpenetration of class and nation, not just in theory but in revolutionary practice. It was Lenin who said of this era that nations become almost as classes.

We should know that this ideological struggle is not new, but has been going on since the emergence of scientific socialism. Today the revisionists falsely wrap themselves in the banner of the Bolshevik Revolution, misquote Lenin on “ultra-leftism”, and claim to represent proletarian politics. But in the early imperialist period in Europe it was precisely Lenin and the Bolsheviks who led the fight to recognize and support the world importance of national liberation struggles—even in the case of premature, unsuccessful struggles in small oppressed nations. This has always been the communist stand.

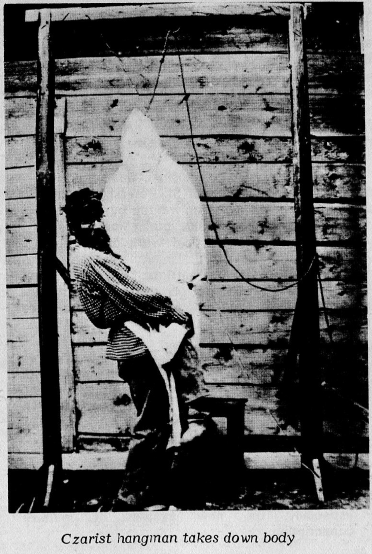

The issue in Europe came to a head over the Easter 1916 Irish Rebellion. That Easter Day a few hundred Irish revolutionaries, mostly from the petty-bourgeoisie, staged a brave but ill-conceived uprising. They took over the Dublin Post Office and declared Irish independence. Within hours they were crushed; most of the Irish rebels were hanged by the British. There was no general rebellion. Yet that event marks the historic beginning of the present Irish Republic. This small armed action was mocked by the European revisionists, who put it down as a “putsch...which not withstanding the sensation it caused, had not much social backing.”

Lenin publicly defended the unsuccessful Irish military action, showing the vital interconnection between the international class struggle and the movements for the independence of oppressed nations. In 1916 the European workers’ movements as a whole were still weak and politically not very revolutionary. Lenin admitted this, and reminded everyone of the world importance of the independence struggles of small oppressed nations, who were helping create a world imperialist crisis:

“In the colonies there have been a number of attempts at rebellion, which the oppressor nations naturally did all they could to hide by means of a military censorship. Nevertheless, it is known that in Signapore the British brutally suppressed a mutiny among their Indian troops; that there were attempts at rebellion in French Annam (i.e. Indochina) and in the German Cameroons (i.e. Afrika); that in Europe, on the one hand, there was a rebellion in Ireland, which the ‘freedom-loving’ English, who did not dare to extend conscription to Ireland, suppressed by executions…

.......

“This list is, of course far from complete. Nevertheless, it proves that, owing to the crisis of imperialism, the flames of national revolt have flared up both in the colonies and in Europe, and that national sympathies and antipathies have manifested themselves in spite of the Draconian threats and measures of repression. All this before the crisis of imperialism hiht its peak; the power of the imperialist bourgeoisie was yet to be undermined… and the proletarian movements in the imperialist countries were still very feeble.(1)

In showing the importance of small oppressed nations to the world revolution, Lenin was also dismissing the misleading doctrine of “pure” or abstract working class revolution. In his period as well as ours, the proletarian movement could not be the revolution, but could only lead a revolution composed of differing class, national and political forces:

“To imagine that social revolution is conceivable without revolts by small nations in the colonies and in Europe, without revolutionary outbursts by a section of the petty bourgeoisie with all its prejudices, without a movement of the politically non-conscious proletarian and semi-proletarian masses against oppression by the landowners, the church, and the monarchy, against national oppression, etc.--to imagine all this is to repudiate social revolution. So one army lines up in one place and says, ‘We are for socialism’, and another, somewhere else and says, ‘We are for imperialism’, and that will be a social revolution! Only those who hold such a ridiculously pedantic view could vilify the Irish rebellion by calling it a ‘putsch’.”(2)

When the Russian Revolution itself is examined we can understand Lenin’s heated insistence on the importance of national liberation struggles to the world future. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution was world-historic, marking the communist movement’s breakthrough in creating the first modern communist party, organized on a professional revolutionary basis and guided by proletarian ideology. For years this party had done political struggle with European revisionism, upholding the right of oppressed nations to self-determination in both theory and practice. It was a party that had consciously struggled internally for a correct understanding of internationalism.

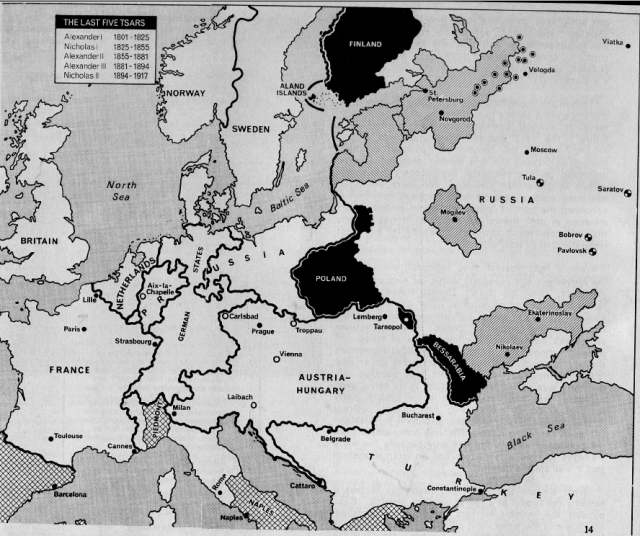

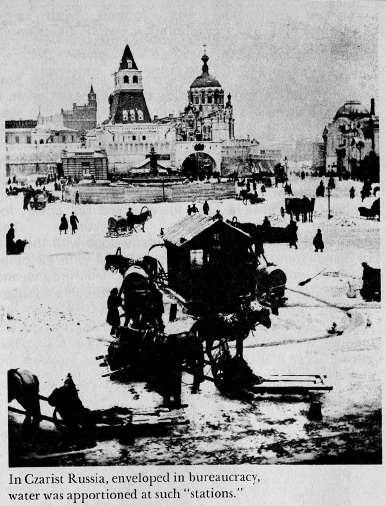

Lenin’s fight against false internationalism within the movement and especially within his own party was important. Like the “U.S.A.”, Czarist Russia was not really a nation but an empire. The dominant Great Russian oppressor nation had annexed many smaller nations into its continental empire. False internationalist views downgraded the importance of these oppressed nations, with many in the Russian movement wanting to simply continue the old Empire under new “socialist” management. As Lenin kept pointing out, the Party was calling itself “Russian” in its name even though it was not Russian, but an all-Empire party with much of its membership non-Russian. Great Russian chauvinism and hidden attraction to Russianism even had many followers among communists from the oppressed nations. It was only because the party managed to hold to a correct line on internationalism that it was able to develop.

What we are told about the revolution is that it remains the model of a “pure” workers uprising. Supposedly the militant workers’ councils in Petrograd, Moscow and the other main cities, led by the Bolshevik Party, overthrew capitalism by suddenly storming the palace and other centers of power. These are the images popularized by the Hollywood movie “Reds”. All this is shallow—to the point of being misleading half-truths.

To understand the Bolshevik Party we have to look at its early practice, the reality of long years of surviving and building an illegal (and armed) underground apparatus. One key to their initial organizational survival was the fact that the Bolsheviks had a rear base area only a few miles from the Russian capital of St. Petersburg (now called Leningrad). This was as life-giving to Lenin as the early Bolsheviks as the mountain border regions were to Mao, Chu Teh and the early Chinese Red Army. Their rear base was Finland, a semi-autonomous but subject nation to Czarism. Finland was called “the Red base”.

Finland was a Russian possession (obtained from Sweden), but one which for ninety years had been permitted to retain much internal autonomy—with its own legal code, police, university system, and so on. That changed in 1898, when the Russian Empire appointed a new colonial Governor-General, Nicholas Bobrikov, and gave him orders to gradually strip away all the national rights the Finnish people had. This gave birth to a broad movement of anti-Russian resistance by the Finns, of all political leanings from left to right. In that atmosphere Russian revolutionaries received the sympathetic help of the Finnish nation.

The Finnish capital, Helsinki, was only forty miles from the Czarist capital of St. Petersburg. It became a sanctuary where Russians wanted by the Czarist secret police could quickly hide out. More important, for years much of the practical work of the Bolsheviks was organized through Finland. One historian describes how Finnish patriotic reaction to Great Russian tyranny swiftly evolved from non-violent to violent resistance, including support for Russian revolutionaries:

“Passive resistance for Bobrikov’s policy was organized by a group known as the Kagal. One of its leading members, Adolf Torngren, developed close contacts with Russian liberals, but also occasionally helped Russian revolutionaries.

“The principle of passive resistance was to stand firm on Finland’s laws and refuse cooperation with arbitrary measures, such as, especially, the new system of military conscription.

“...Finnish officials were in a difficult position; Russian pressure was steadily intensified, and not all could be expected to sacrifice career and livelihood. The meaning of duty and loyalty, of law and conscience, formed an ever more painfully tangled knot, which there was no agreed way to unravel.

“In this situation, a few began to turn from passive to active resistance. After several schemes had been tried and abandoned, Bobrikov was eventually assassinated in June 1904. In November of that year, the Finnish party of active resistance was formed, with a programme of collaboration with Russian revolutionaries.

This scholarly account goes on to describe how Finland lived up to its name as the “Red base”, given it by the Bolshevik Vladimir Smirnov. As Smirnov was half-Finnish, he was assigned as an organizer of the support base, in coordination with the armed underground. Although Smirnov was working visibly among the masses, building solidarity, his style of work was different from that considered by us as “legal” or “public”. He used a false identity and full cover, for example, and communicated clandestinely. The Bolsheviks’ mass work was regularly done with the use of clandestine methods and coordinated with all other areas of work (even those that were underground and armed). In other words, mass work and being “above-ground” didn’t mean lack of precautions, secrecy, etc. “Above” and “under” were more a question of compartmentalization rather than the widespread error in our movements that regards mass work as needing no security precautions or clandestinity.

“The description of Finland by Smirnov as ‘the Red base’ is borne out of many documents in the archives of the governor-general of Finland. One the whole, Finnish police and officials performed their duties in accordance with Finnish law, and were reluctant to accept Russian direction. The Russians had their gendarmerie in Finland, but its powers were limited. The Finnish police would hold suspects only for a certain time; arrested Russian revolutionaries were set free after a month, unless proper documentation of the crimes they were alleged to have committed in Russia was received from the Russian authorities within that time.

“This Finnish law saved the chief underground organizer of the Russian social democrats, Leonid Krasin (‘Nikitich’), by profession an electrical engineer (and a brilliant one, as he was later an outstanding Soviet diplomat, at his death in 1926 he was Soviet representative in London).

“Arrested in Finland in March 1908, Krasin was imprisoned in Vilpuri. Several attempts to escape failed. But after a month he was freed, as the Russian authorities had not supplied the necessary documentation to justify his continued detention.

“The staff and students of a bolshevik school and workshop for explosives, situation in Finland, who were arrested in 1907, were given up to Russia only after a prolonged legal battle between Finnish and Russian authorities.

.......

“Smirnov and his colleagues could count on help from many ordinary Finns, in addition to socialists and active resisters, in the work forwarding literature (ferried from Stockholm) from Turku and Helsinki to St. Petersburg.

“Among the most useful helpers were Smirnov’s old mother, in whose knitting secret messages were always safely concealed, and Finnish engine-drivers, manning the trains that went through to the Finland station in St. Petersburg. Arrived there, literalture was taken away by workmen in the tool-boxes.

“A Finnish railway official in St. Petersburg gave Smirnov contacts among station staffs along the whole line between Vilpuri and the frontier station of Beloostrov. For urgent messages, it was even possible to use the private channels of the railway telegraphic system.

“When revolutionaries are described as being ‘in Finland’ at this time, it should be remembered that this often meant small places, such as Terijoki and Kuokkala, on the railway line close to the Russian frontier, only a few miles from St. Petersburg. Not all writers seem aware of this; one sometimes reads for example of Lenin retreating ‘deep into Finland’, when his refuges were usually within about forty miles of the Russian capital. And his couriers could commute almost as quickly as though between London and St. Albans, Stockholm and Sodertalje, or Copenhagen and Roskilde.

“At the beginning of 1903, Smirnov became a teacher in Russian at the University of Helsinki. With the widespread anti-Tsarist mood in Finland, he had no difficulty in finding assistance. Sometimes he received useful information from the deputy police chief of Helsinki, through friends in shipping he could obtain cut-price steamer tickets, and later had Lenin’s manuscripts typed in Finnish government offices. His home in Helsinki became the chief intermediate stage for revolutionaries travelling to or from Russia, including Lenin and (in 1907) Trotsky.

“Revolutionaries could even assemble in Finland in fair safety, and many large and small meetings were held there, such as the bolshevik conference at the Tampere in December 1905, where Stalin met Lenin for the first time.”(4)

The support network organized by Smirnov delivered funds to a section of the underground responsible for military affairs. Finnish radicals became familiar with a young Russian pianist whose real name was Nicholas Burenin:

“Burenin was known in Finland as an amateur impresario, arranging charity concerts for needy Russians. Finnish resisters knew him as ‘Victor Petrovich’, one of the mysterious Russians who kept appearing in Helsinki. Adolf Torngren described him as a pleasant young man evidently of wealthy family, son of a Moscow cotton king, and added condescendingly that he seemed somewhat vague and unpractical.

“This talented pianist Burenin, after the bolshevik revolution for a time director of the Soviet State Opera, must often have smiled his agreeable smile when telling Finns as little as possible of his real affairs. From early 1905, he was head of the bolshevik fighting organization in St. Petersburg, under Krasin’s direction. As smirnov was the expert in smuggling literature through Finland, so was Burenin the specialist in weapons and explosives.

.......

“Burenin, too, advanced far in the underground. When the bolsheviks began to prepare for uprising in St. Petersburg and established early in 1905 a fighting organization with Burenin, responsible to Krasin, at its head, the main task was finding arms.

“They were scarce. But miscellaneous weapons, and particularly explosives for bombs, could sometimes be obtained in Finland—there were many reports of stores of explosives being raided—and rifles were sneaked out of the arms factory at Sestroretsk, near the frontier, where several workers in the factory assisted.

“The transport of such valuables to the capitla occupied several specialists, of both sexes. Afterwards, women particularly recalled the harsh reek of dynamite (known conspiratively as ‘uncle’, and worn in belts and bandages close to the body)--overpowering when sweating in a close atmosphere. They used to apply strong scent heavily, and travelled for preference on the open platform at the end of the railway carriage, even in hard frost.

“Rifles were divided into barrels and stocks, and the pieces suspended from a towel or cord and tied around the neck. Some girl students became virtuosos in this art, and could carry up to eight rifles.

“A transporter laden with rifles in this way was not able to bend. This could be awkward. One girl, known as ‘Fat Fanny’, was once rigged out with rifles together with a male colleague, ‘Molecule’. Suddenly Molecule noticed that a piece of cord, part of Fanny’s apparatus for carrying rifles, was trailing from beneath her skirt. Neither could bend, and the street was full of people. The threat of discovery was averted by boarding a double-deck tram and Fanny mounting the stairs to the top deck first, while Molecule wound up the cord behind her.

.......

”Not all the adventures of Burenin and his group were so whimsical. Several enthusiastic amateurs set about producing bombs. Burenin was once presented with a basket containing home-made infernal machines. An expert he consulted was horrified at their primitive construction, and told him to get rid of them at once, no easy task. So half an hour before he was to play at a concert, Burenin found himself scrabbling on the steep and slippery bank of a canal, trying to drown a dangerous bomb.

“The situation was improved by setting up a bomb workshop and chemical group, which a a distinctly scholarly atmosphere—leading members were ‘Alpha’ and ‘Omega’, while the expert advisor was a professor known as ‘Ellipse’. On Krasin’s instructions, Trotsky, a leader of the St. Petersburg Soviet in 1905, was supplied with two powerful hand grenades by this group. Plans for a satisfactory bomb were obtained from a Bulgarian expert in Macedonia, and large quantities of fuses, bought in France, were imported through Finland. ‘Natasha’ specialized in this job, travelling with her infant daughter as cover.

“For the comings and goings in Finland of Burenin’s group, the chief meeting-place was a well-known liquor shop in Helsinki run by Valter Sjoberg. This was an ideal centre, easy to find with its conspicuous sign, and visited by all sorts of people. Sjoberg was unfallingly helpful, whether the job was corseting Natasha with fuses, contacting shipping firms, or passing on tips from the Finnish police. Another advantage was that next door was a barber’s shop, useful for quick changes.

“...It may seem strange that revolutionaries were able to leave or enter Finland with little difficulty. For this they had to thank particularly their Finnish friends like Sjoberg in Helsinki, and a socialist, Valter Borg, in Turku, who had influence with shipping firms. Passport control, too, was normally carried out not by Russian gendarmes, but by the Finnish police.”(5)

This look at the practical details of the Bolshevik Party shows how they were not super-human revolutionary figures. They were a handful of young rebels, overcoming their inexperience and struggling to build an organization that was not only clandestine but professional. Before the 1905 Revolution there were less than two hundred Bolshevik cadre. Their tactics were crude and makeshift. But they were able to build a revolutionary vanguard against a powerful Empire because they joined with the rising tide of Finnish national consciousness. Only those who refuse to see revolution as it actually is, can fail to see the connection between the breakthrough of world socialism and the rebellion of a very small, oppressed nation. The Finns combined a struggle against their own bourgeoisie and the oppressing Czarist Empire with aid to the revolutionaries of the Great Russian oppressor nation. They were practicing internationalism, which in turn aided their own struggle for independence. Who can say that the Finnish national struggle, which never reached the stage of successfully overthrowing its own bourgeoisie, still had not made an important contribution to world revolution?

Even after the bitter defeat of the 1905 Revolution and the increased severity of Czarist rule, the Finnish people aided the Bolsheviks whenever possible. When the chief Bolshevik organizer in Finland was arrested in 1908, the Finnish police released him (so he could escape) on technical grounds.

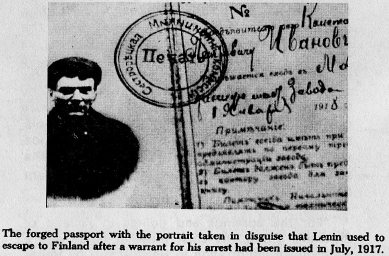

In 1907 the Czarist repression had become so fierce that Lenin’s underground security was no longer good enough. He was forced to leave for Western Europe. Since it was unsafe to try and take ship passage straight from Helsinki, Lenin hid out in the remote Aland Islands, between Sweden and Finland, until he could get an outbound ship. Alone, Lenin was taken care of by Finnish farmers and workers. Even the policemen patrolling one island helped take care of him. Lenin told the Finns that a nation whose police fought oppressors would surely get independence. Ten years later Lenin again had to take shelter in Finland. This time, in July 1917 when the bourgeois Kerensky government, which had brielfly filled the void when Czarism felll, ordered Lenin’s arrest as an alleged German agent. Lenin was secretly protected by the chief of the Helsinki militia (which was the functioning as the local police), the very person who was supposed to be leading the hunt for Lenin.(6)

This seldom-discussed story is only one chapter in the relationship between the proletarian struggle in Russia and the liberation struggles of oppressed nations. It refutes an abstract picture of the Bolshevik Revolution that has been spread here in the U.S. Empire. Not only was the role of the small oppressed nations much greater in the Bolshevik Revolution than he have been told, but their struggle was more like ours than we may think. Making revolution was not just orating before crowds of factory workers. The problems of correct political line and the problems of practical work drove the young Bolsheviks.

Starting with nothing but will, every step involved innumerable new practical challenges—from underground security problems, to distributing political literature to the masses, to recruiting people to carry raw explosives past the Czarist customs inspectors (similar to the Battle of Algiers). We should not forget that their small party was underground, hardened by years of practical work and terrible setbacks—virtually wiped out after the defeats of 1906-1907. It was precisely such a party that could grasp the interrelationship of national liberation to socialist revolution—especially inside “their own” empire.

Here history gives a warning—no one and no party can simply rest on their laurels. The two-line struggle on the national question within the Bolshevik Party reversed itself after the new Soviet government was formed. Great Russian national chauvinism in false internationalist disguise crept back into power. Lenin, who had led the principled battle against this new deviation, was increasingly isolated politically within the Party in his last few years of life. He was in a small minority within the Party. The other major Party leaders, including Stalin and Trotsky, all opposed his views. Lenin, ever forthright, wrote: “Scratch a Bolshevik and you’ll find a Great Russian chauvinist.” His death in 1923 marked a nodal point. Henceforth, Russian oppressor nation chauvinism would do its work disguised as internationalism. This had an unanticipated effect on the development of the world revolution.

In the making of their Revolution the Bolsheviks not only showed internationalism in practice, but provided lessons for us about the importance of small nations as well as large ones. There is a tendency within the U.S. Empire, fostered by colonial domination, to consider only the “u.s.a.” a “real” nation. Small nations such as Hawaii, New Afrika, Independent Oglala Nation, etc. are widely—even by Third World people—not thought of as either very real or politically decisive. The notion that small oppressed nations are as real as large oppressor nations is one that still needs reinforcing here. And practice proves that small nations such as Finland or Guinea-Bissau or Vietnam can, at decisive points in the struggle, exercise a world-historic influence.

Footnotes

(1). V.I. LENIN, “Discussion on Self-Determination Summed Up”, On the National Question and Proletarian Revolution, Moscow, 1972, p. 142-148.

(2). Ibid.

(3). MICHAEL FUTRELL, Northern Underground, London, 1963, p. 51-65.<

(4). Ibid.

(5). Ibid.

(6). Ibid.