False internationalism is a dangerous weapon against revolution in the hands of revisionism, because it uses genuine respect for proletarian unity in order to reintroduce oppressor nation hegemony. Proletarian unity is the recognition that the oppressed and exploited masses of the world, led by the proletariat as a world class, not only have common interests but make up a world socialist revolution. False internationalism tries to manipulate this need for unity across national lines in different ways: in Euro-centric or oppressor-nation dominated politics, in liquidating national liberation activities into “international” forms unresponsive to the masses, and so on. What is common in this is that despite the good intentions of so many revs who get caught up in such things, the results are really neo-colonial. We can see this in our own histories.

Within the communist movement, there was a period when the issue of false internationalism took on world significance. That was the Comintern period of 1920-1943, when modern communist parties were first being born throughout the world under the direction of the Soviet Union. In every case these young parties had to undergo many trials. Communists who could not understand false internationalism were in all cases defeated by revisionism. In Europe, Afrika, Asia, Latin Amerika and North Amerika, those national movements and communist parties which could not pass that trial were destroyed. The defeat of proletarian movement in Algeria, Mexico, Italy, New Afrika and many other nations then is recorded in history. The experiences of this Comintern period allow us to throw light on our own movements today.

Again, we must remember that false internationalism is an alliance between petty-bourgeois/lumpen elements in both oppressor and oppressed nations. In this alliance the “allies” are used to promote opportunist elements into leadership over the colonial peoples.

This is not an unfamiliar mechanism when practiced by imperialism itself. After all, indigenous nations continually have to struggle against “tribal chiefs” and “tribal chairmen” installed by the U.S. government as neo-colonial puppets. And New Afrikans are also used to having the U.S. Empire finance and publicize selected leaders for them (ministers, bourgeois politicians, civil rights leaders, etc.) instead of any they might choose themselves.

But this is not, unfortunately, a distance phenomenon; rather, one that is politically too near to us. For even within revolutionary movements, “allies” are found to help promote one petty-bourgeois/lumpen group or another as the supposed leaders of the oppressed nation. In the mid-1970s, U.S. settler Left group were falling all over themselves to proclaim the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP) as the leadership of the Puerto Rican liberation struggle—although that party was only one of a number of P.R. revolutionary organizations and not necessarily the most correct. The same thing happens within the New Afrikan Liberation Movement, in which petty-bourgeois/lumpen cliques are partially sustained and and pushed forward by various settler Left “allies”, who proclaim them as their selected leadership for the New Afrikan nation. The Comintern experience shows us how common such false internationalism has been in world politics.

How powerful a revisionist tool is false internationalism? Picture the following scenario: A young communist leader named Mao Zedong was suddenly thrown out of the Red Army, although he had successfully fought for six years to build a worker-peasant guerrilla army of a new type. Overnight Mao was removed from his post as a political commissar of the Red Army, removed as secretary of the Soviet area united front committee. A new party security apparatus purged those cadre who tried to still practice Mao’s political-military doctrines. Some guerrillas who supported Mao were summarily dealt with as supposed security risks.

To replace the “opportunist” Mao Zedong, the party leadership introduced an obscure German “communist” as a new secret leader of China’s Red Army. This untried European had great authority, since he had just been sent from the Comintern to oversee the Army. He was supposedly much more “Marxist” than Mao, a top European military expert. The German’s military writings, published under a Chinese pseudoname, were hailed by the party leaders as an improvement on Mao’s. Red cadres and soldiers were set to studying the German leader’s strategy, which was to replace all the strategy and tactics learned in a hundred battles by the Red Army.

Unfortunately, that German’s military learning came from a classroom in Moscow; he had never been in an army or won a battle. His Chinese allies didn’t care how many defeats he led the Chinese people into, since with his backing they could at last isolate Mao Zedong and his ideas. Finally the criminally incompetent generalship of the German and his Chinese allies led to the loss of the entire liberated zone—hundreds of thousands of peasants died, and in the German leader’s panicked flight half the central Red Army was lost. In one stupid river crossing the German got 30,000 Red fighters killed. Red commanders had found their units decimated in a few weeks. Within six weeks he had lost two-thirds of the revolutionary army. That was a time of bitter losses, of possible extinction.

To us this scenario may sound so strange that it is little short of science-fiction. It was real, however. Those incredible events did take place in China during the years of 1932-1935. Party, army and national liberation movement took terrible blows, and faced extermination, before that epidemic of false internationalism was broken. Even a strong party and an army of three hundred thousand soldiers was brought almost to its knees. It would be arrogant for us to believe that we are somehow so advance that false internationalism is no problem for us. As we shall see, Peoples’ War in China could only develop, step by step, in intense two-line struggle within the revolution.

There are several things about the Comintern (Communist International) that we should notice. First, that it was the most sweeping experiment in organizational internationalism the communist movement has ever seen. One single structure united communist in over sixty nations, deliberately disregarding national distinctions. Although people were very careful to publicly say that the Comintern’s relationship to individual communist parties was only “advisory”, the Comintern was in reality a disciplined world super-party. The member communist parties were even referred to as “national sections”. While day-to-day leadership rested in the hands of the various national communist parties, the Comintern’s center in the U.S.S.R. ultimately led every communist in the world.

The Communist International was part of a European socialist tradition, and was the third of the internationals. Starting from the days of Marx and Engels, it was the practice of European revolutionary parties to all unite in continental associations. It was therefore quite natural for the Bolsheviks to initiate new (“Third”) international to oppose the already existing Second International of the reformist Social-Democratic Parties. Although the Comintern was founded in 1919 by the Russians, it didn’t become a true world body until the 2nd Congress in June 1920. The Bolsheviks had issued a call for left socialists in Europe to split their parties and regroup into new communist parties around their new socialist state. In colonial nations they called upon revolutionaries to join the new international first individually, and later as whole parties. To join the Comintern was a heavy matter, and one by one, in nation after nation, new communists joined in the spirit of internationalism, to become full participants in the world communist movement. In many nations this decision took time. In Vietnam, for example, revolutionaries were not able to form a communist party and decide to join the Comintern until 1930.

While the Comintern was first organized to coordinate the Europe-wide revolution (particularly in Germany) that communists expected within a few years, form the start Third-World revolutionaries were involved. Ho Chi Minh, in exile in France, became a founding member of the French Communist Party in 1920. Sen Katayama, the founder of Japanese communism, was likewise a founding member of the Communist Party USA in 1919. New Afrikan revolutionaries had gone to Moscow for consultation with Lenin and the other Bolshevik leaders.

In form nothing appeared more internationalist to young communists than that. It was a very ambitious step, and in the 1920s and 1930s the Comintern seemed to give the oppressed a world army, complete with proven general staff, fully strong enough to take on imperialism. Comintern representatives from the Moscow center criss-crossed the world secretly bearing orders for new strategies and needed funds, bringing foreign experts to guide strikes, publications or uprisings. Even when the Chinese Red soldiers had no other insignia, they wore simple armbands with two slogans--”Support the Communist International” and “Make the Land Revolution”. The enthusiasm among the revolutionary masses for the Comintern in the beginning years was tremendous.

The second thing about the Comintern was that it represented one form of unity, arising from a concrete historical situation. Many comrades regard internationalism as something like universal brotherhood and sisterhood. To the contrary, internationalism is always realized in specific relationships, with a definite historical and political character. The Comintern was born in the drive of the U.S.S.R., the world’s first socialist state, to rapidly generalize its revolutionary breakthrough from a regional to a world scale. So the Comintern was set up to actually carry out the world revolution. It was hoped that by using the historic example, the already-proven leadership, and the material resources of the U.S.S.R. In a giant short-cut, capitalism could be swept away entirely in a few years. A completely socialist world was envisioned as an immediate goal, led by industrial Europe. Were this to fall, the Bolsheviks feared that imperialism might crush their infant socialism with military and economic encirclement. V.I. Lenin wrote in June 1920 for the 2nd Congress of the Comintern:

“The world political situation has now placed the dictatorship of the proletariat on the order of the day, and all events in world politics are inevitably revolving around one central point, viz., the struggle of the world bourgeoisie against the Soviet Russian Republic, around which are inevitably grouping, on the one hand, the movement for Soviets among the advanced workers of all countries, and, on the other, all the national liberation movements in the colonies and among the oppressed nationalities… Consequently, one cannot confine oneself at the present time to the bare recognition or proclamation of the need for closer union between the working people of the various nations; it is necessary to pursue a policy that will achieve the closest alliance of all the national and colonial liberation movements with Soviet Russia...”(1)

This Comintern of the Bolsheviks made positive contributions to the world revolution in the early 1920s, initially helping to spread modern communism to many peoples. But it quickly became a new roadblock to revolution. A Russian-oriented organization and a Russian-oriented political strategy was unable to meet the needs of widely diverse national situations. Far worse, the explicit dogma of a Russian superiority in political matters fostered a revival of crude European chauvinism in new revolutionary dress. The supposedly internationalist form of the Comintern too often boiled down to arrogant foreign agents “meddling in our affairs” (to use Mao’s words); their alliances were with petty-bourgeois revisionists who were only too glad to trade away the self-reliance of their own people. Russian intervention did not mean that there was a frank, respectful, two-way exchange of views on political matters, or that criticism on possible errors was shared. The Comintern had one-way criticism, which tried to impose Russian views on anti-colonial struggles whether the oppressed nation agreed or not.

The most important effect of Russian oppressor nation intervention was not the pushing of wrong policies—it was the symbiotic relationship with opportunist cliques within the national liberation movements. Just as the remote peasant areas were the sheltering rear base for Mao Zedong and the correct revolutionary line, so the Comintern and Russia became the rear base for petty-bourgeois opportunism within the Chinese revolution. False internationalism was thus welcomed and promoted by certain types of Chinese leaders who were petty-bourgeois nationalists. This has parallels to the struggles within the U.S. Empire, where the U.S. settler Left has acted as the rear-base area to aid and promote opportunist Black leadership that has misled their liberation struggle.

Comintern internationalism was ultimately false, because it was both an unequal unit based on oppressor nations still dictating to the oppressed nations, and an incorrect perspective of building movements whose leadership was not responsible to the masses. Correct relations between revolutionaries of different nations must be based on the principle of equality and mutual respect; this means respect for the right of self-determination of the oppressed nations in all matters. Communists must uphold the principle that the masses of an oppressed nation are the masters of their own destiny, and must be responsible to them by adhering firmly to their interests, to the foundation and objectives of the liberation struggle, and by “committing class suicide” in firmly merging themselves into the new proletariat.

While modern communism spread “like a prairie fire” across the colonial world, the Comintern’s European-centered outlook fostered a fad of Third-World imitation Russians. To these eager students everything European was scientific, while everything to do with their own national struggles and story was backward. Revolutionary leaders like Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong were labelled “bourgeois nationalists”. Even in Vietnam it had reached the point by 1934 that the Bolshevik, theoretical journal of the Indochinese Communist Party, proclaimed that Ho Chi Minh “advocated erroneous reformist and collaborationist tactics… based on his bourgeois nationalism.”(2) Ho’s “error” was urging his comrades to lead in building a broad national liberation front against the colonial enemy. Far from providing advanced international leadership to the new communist parties, the Comintern was wittingly or unwittingly an international structure with accelerate the most unrealistic and opportunistic tendencies within the national movements. We can accurately judge the level of political confusion by the sight of even our Vietnamese comrades denouncing their nation’s greatest revolutionary leader.

CHINA: THIRTEEN YEARS OF STRUGGLE

Correct leadership for the revolutionary war in China was forged in a two-line political struggle that lasted twenty-five years (thirteen years of which saw the correct ideas in the minority). False internationalism played a major role against that liberation struggle. This was the clearest possible example of an opportunism that covered itself with false internationalism, and its effect on the armed struggle.(3)

In this current season we can learn a lot from that two-line struggle. All too often comrades become discouraged because advanced ideas have not yet prevailed inside the struggle. Others dismiss the worth of advanced ideas at all, arguing that these ideas have been passed around but folks in the movement for whatever reason won’t pick them up. Yet Mao Zedong, one of the greatest revolutionary leaders in history, was in the political minority in his party for 13 years. Several times he was dismissed from the leadership of the party. More than several times he lost command of the army. His advanced ideas were opposed by the combined past and present leadership of the party, plus all “foreign friends”, despite the fact that for many years he could prove that the customary, “regular” way of doing things was a disaster.

New answers, new ideas, cannot get taken up by acclamation on first hearing, and are in fact not even developed at first. Advanced ideas here have not been successful in large part because they have not been so advanced, still being a mixture of old bourgeois ideas, revolutionary ideas applied in a mechanical way, and so on. Only protracted struggle, which definitely includes real scientific methods of analysis, can arrive at correct answers. What separated Mao from the established Movement leadership was not thirteen years; his thinking was in a different place; his outlook was proletarian in that it was firmly rooted amidst the oppressed while applying real scientific methods to create the conditions for success.

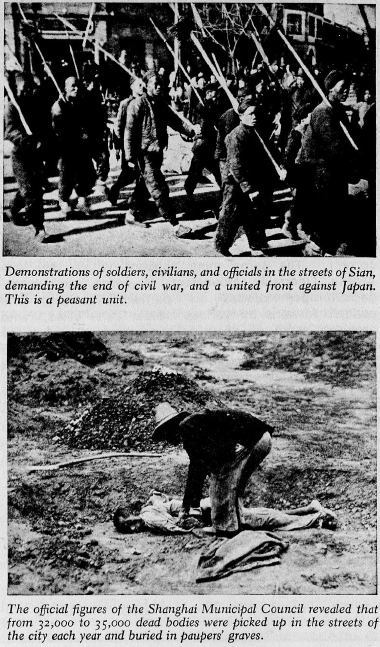

To understand the influence of false internationalism we have to see how powerful the impact of the Bolshevik Revolution was on the Chinese people. Their liberation struggle had gone on for generations, yet still the “dark night of slavery” held China in its grip. While China was the largest nation on earth, and one which had reached a high stage of civilization when Europe was still in the Dark Ages, she was by 1920 a backward neo-colony of imperialism. The old Manchu Dynasty still sat on the imperial throne in the palace of Peking, but each foreign power had its own enclaves, bases, its own economic enterprises, and its own troops on Chinese soil. Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Russia, U.S.A. and Japan jealously ruled China together. Chaos and misery grew. China’s own native handicraft industries had been wiped out by cheaper industrial imports, while minerals and even the railroads were owned by Western imperialism. Since China was very large, but with a decaying society and a weak central government, vast areas had fallen into chaos. Much of China was ruled by one or another warlord army. These warlord armies were like giant street gangs, swelled by homeless peasants and engaging in looting for survival. The warlords themselves were wealthy, paid by the local landlords and the foreign interests. China was a scene of constant civil war between all these armies, and no national unity at all.

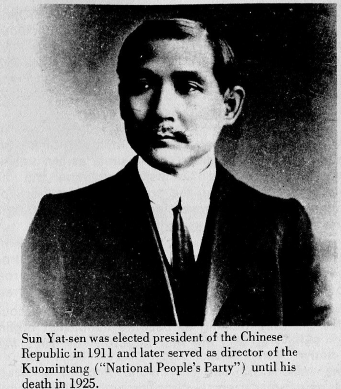

During the fifteen year Taiping Rebellion a rebel army distributed land to the peasants and unbound women’s feet before being finally crushed by the Western-aided imperial forces at the Tatu River in 1864. In 1911 the Great Revolution took place, ending the decadent imperial government. But the new bourgeois democratic government of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the “father of modern China”, tried in vain to establish a democratic republic by paying some warlords to serve as an army for his government of unification. Masses of Chinese patriots had taken part in these national wars. Young Mao Zedong first became a patriotic soldier in the nationalist armies of 1911, ten years before he became a communist. After almost a century of uprisings, mass movements and civil wars, the Chinese people were still searching for the correct path that would lead them to victory.

The Bolshevik Revolution, which not only overthrew capitalism but also successfully defending itself against the invading armies of the U.S., France, Britain, Japan and other capitalist nations, attracted much interest in China. Many democratic-minded patriots saw in this communism the long-sought-after answer to China’s future. In June 1922 Dr. Sun Yat-sen met with one of China’s most brilliant commanders, Brigadier General Chu Teh. He wanted Gen. Chu Teh to rejoin his forces and help lead another military expedition to subdue the northern warlords who held Peking. Chu Teh and his companion, another nationalist officer, fraternally refused. Chu Teh, who went on to command the Red Army, recalled:

“...I had lost all faith in such tactics as the alliances which Dr. Sun and his Kuomintang followers made with this or that militant. Such tactics had always ended in defeat for the revolution and the strengthening of the warlords. We ourselves had spent eleven years of our lives in such a squirrel cage. The Chinese Revolution had failed, while the Russian Revolution had succeeded, and the Russians had succeeded because they were Communists with a theory and method of which we were ignorant.

“We told Dr. Sun Yat-sen that we had decided to study abroad, to meet Communists and study Communism, before re-entering national affairs in China.”(4)

Communism took root in China, gradually becoming a material force as it was taken up by the workers and peasants. Soon in some areas peasants noticed that even the mention of this new word made the hated landlords afraid—and took to shouting communist slogans at them even when they didn’t know who or what this communism was, just to enjoy the effect it had. Dr. Sun Yat-sen had turned all China over by putting forward his new program, the famous Three Peoples Principles to save the nation: national independence, political democracy, socialism. In 1923 Dr. Sun led the nationalist movement into a historic alliance with the Soviet Union and the small Chinese Communist Party. This was the first United Front, when bourgeois nationalists and communists openly worked together in the Kuomintang government.

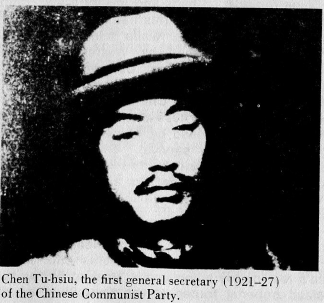

In the 1923-1927 period of the First United Front the two-line struggle emerged very sharply within the ranks of the Revolution. The Party secretary-general was then Chen Tu-hsiu, one of the most prestigious of China’s Mandarin intellectuals. He was someone who feared struggle. Chen Tu-hsiu was just a front-man, however. The de facto leader of Chinese Communism was Michael Borodin, the famous special representative of the Bolshevik Party Politbureau to the Kuomintang. Borodin was a Bolshevik who had spent the ten years before the revolution in Valparaiso, Indiana (where he went to college) and Chicago, where he and his Euro-Amerikan wife had been active in the movement. After the 1917 Revolution he had returned to Russia, and on the basis of his foreign experience was made an important Comintern agent. Borodin was no closet figure in China. He held court in Canton, the nationalist capital; he spoke at mass meetings, negotiated with all political groups, was openly enjoying his role as one of the most powerful leaders over the Chinese nationalist movement. All the Chinese communist leaders, including Mao Zedong, had to come to Borodin to get their policies approved.

This European meddler made common cause with the conservative Chen Tu-hsiu tendency within the Chinese Communist Party. Their joint policy was one of “all unity and no struggle” with the Chinese bourgeoisie. Comintern policy saw the first priority as the defeat of reactionary warlords, with China reunified and made independent under the leadership of the bourgeoisie. The Comintern opposed a separate communist army, class struggle against the landlords, or communist uprisings. The nationalist united front was just, and desperately wanted by the masses. But when Borodin and Chen Tu-hsiu so freely gave the bourgeoisie everything, with no communist army or giving power to the masses, they were really signing death warrants for millions.

Mao Zedong acidly summed Borodin up: “Borodin stood just a little to the right of Chen Tu-hsiu, and was ready to do everything to please the bourgeoisie, even to the disarming of the workers, which he finally ordered.” False internationalism literally ripped the guns out of the hands of the Chinese workers and peasants, and left them defenseless before the imperialist terror.

The U.S.S.R. built up the Kuomintang military to counter the warlords; although this nationalist army had many communist and patriotic officers and soldiers, in its overall character it was still a bourgeois warlord army. Borodin organized Whampoa, a new Kuomintang military academy initially staffed with thirty Russian officers. A Russian general was sent to become the actual battle commander of the army. Even the small—and strongly patriotic—nationalist navy was commanded by a Russian officer. Borodin sent a young aide of Dr. Sun Yat-sen to Moscow for military training, grooming him to become commander-in-chief of the Kuomintang military. This Chinese general professed his love for Russia and socialism in return for the Comintern’s backing. His name was Chiang Kai-shek.

The nationalist united front expanded revolutionary consciousness among the masses, with worker and peasant unions and anti-imperialist organizations enlisting millions in the nationalist areas. Membership in the Communist Party grew in the first eleven months of 1925 from less than 1,000 to over 10,000 activists. With the sincere support of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, communists by 1925 took over leading roles in all branches of the nationalist movement. This was, however, a castle built on sand. The left-right split within the nationalist movement was not overcome, but was deepening.

During these eventful years the correct line of peasant revolutionary armed struggle under proletarian leadership began to emerge, under the leadership of Mao Zedong and Peng P’ai (the great leader of the first peasant Soviet, who was killed by the imperialists in 1929). The achievements of this 1923-1927 period were considerable: the first scientific class analysis of Chinese society; the first revolutionary peasant organizers’ school; the first militant peasant branch of the party.

While this correct revolutionary breakthough was led by communists, it was opposed by their own Communist Party. Borodin’s ally Chen Tu-hsiu pushed the Party to spit on the peasant masses, saying: “...over half the peasants are petty bourgeois landed proprietors who adhere firmly to private property consciousness. How can they accept Communism?” Mao was forced out of the Party’s Central Committee in 1925. At a special Politbureau meeting the next year Mao tried to discuss the need for mobilizing the peasants before it was too late, but Secretary Chen Tu-hsiu cut him off and denied him the right to speak. Looking back we can see why Mao summed up Chen, the Comintern’s favorite leader at the time, as “an unconscious traitor”. The Chinese Revolution did not smoothly and easily find the correct path to liberation; even basic “common sense” ideas only prevailed after the most bitter political struggle over years.

The correct communist line, under attack from their own Party, grew in the environment of the broad nationalist movement. In 1924 the Kuomintang agreed to set up a Peasant Institute, where peasants could receive full-time training to become nationalist organizers. Peng P’ai was the first director. By 1925 Mao had returned to his native Hunan Province, where he conducted social investigation of the countryside, and began the first peasant branch of communists. The 32 cadres of the branch met in Mao’s family home. In August 1926 Mao took over as director of the Kuomintag Peasant Institute. Poor peasants from all over China got trained as communist organizers, with 128 class-hours out of the course’s 380 hours secretly devoted to military training. Mao’s peasant activities were regarded as so unimportant by both the Kuomintang warlords and his own Party that they were overlooked. Simultaneously Mao became head of the Propaganda Department of the Kuomintang Central Executive Committee. Quietly he was training a network of rural organizers to span China, to give the communist movement a real national mass base. His first class at the Peasant Institute had peasants from 21 provinces and Mongolia.

Suppressed by the Comintern-Chen bloc within the Party, Mao used the nationalist movement to prepare the liberation road to come. In March 1926 Mao wrote the first important theoretical work of the Chinese Revolution—Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society. It was the first scientific class analysis of the Chinese nation, as opposed to the ignorant rhetoric of Chen and his petty-bourgeois clique. This work also was used by Mao as a tool to teach cadres the need for actual social investigation to solve questions. The Communist Party rejected Analysis of Classes in Chinese Society, refusing to even let it be printed in the official Party publication. So Mao, who was editing several revolutionary nationalist political magazines, printed it in Peasant Monthly (the journal of the Peasant Institute). It was then reprinted in Chinese Youth, a revolutionary nationalist young soldier’s journal edited by communist Chou En-lai. The fundamental scientific analysis of the Chinese Revolution was thus first published within the broad nationalist movement, not by the Comintern-led Communist Party.

Mao’s prolonged investigation of the countryside had led him to see the peasant masses as the key to liberation. “Formerly, I had not fully realized the degree of class struggle among the peasantry.” In Hunan, Mao’s home province, the peasants had a rich tradition of uprisings. They had played a large part in the Taiping Rebellion that raged for fifteen years in the 19th century. In 1906 the Ko Lao Hui, a secret peasant society, led an attempt to overthrow the old imperial government. Another armed uprising took place just three years later, leaving in its defeat a bloody wake of executions. In Mao’s own village of Shaoshan he had witnessed the same secret society leading a revolt against a landlord, the rebel peasants having to flee to the mountains to survive as roving bandits.

In 1925 peasant unions and patriotic struggles spread rapidly in Hunan Province. The peasants not only fought the landlords, but demanded the liberation of their nation from colonialism. When the peasants couldn’t understand the communist slogan “Down with Imperialism!”--imperialism was first translated into Chinese as “emperor-countryism”--Mao simply explained that it just meant “Down with rich foreigners!” A 1926 spontaneous peasant revolt in Hunan was crushed. Mao pointed out that the peasant not only displayed revolutionary consciousness, but that “all the lumpen proletariat joined them very courageously.” He saw the main lesson of their defeat was that “they did not have the proper leadership.” Mao in 1926 saw the oppressed masses as more advanced than their supposed leadership. He told a friend that if the Party would use the peasant cadres training at the Peasant Institute to start guerrilla war it would save the Revolution.

But the Comintern-Chem clique had no plans to go against the Chinese national bourgeoisie. Their right deviation undermined the revolution in all areas. Leadership of the national liberation movement was given to the bourgeoisie, who were supposed to lead the struggle against imperialism. The Land Revolution was chained by their policy of exempting families of allied Kuomintang officers and warlords from expropriation; since all landlord families had such political connections, in practice the Comintern-Chen program was using the authority of the Revolution to protect the oppressors.

While Russian experts and guns poured into building the bourgeoisie a large national army, the Party itself had no military organization. Proclaiming that the main threat to the united front was “excesses” by angry workers and peasants, the Comintern-Chen clique kept the masses disarmed. Mao was ordered repeatedly to follow the line of “limitation of peasant struggle”, to stop his peasant comrades from arming and mobilizing. Although the two-line struggle was very sharp, most communists were fooled by the authority of the “internationalist” clique.

This period ended in mid-1927. The fool’s paradise of the Comintern-Chen clique collapsed as the bourgeoisie put its own class dictatorship into effect. So long as Dr. Sun Yat-sen had lived, his noble influence protected the patriotic united front. But in early 1925 he died of cancer, touching off a power struggle for control of the Kuomintang. General Chiang Kai-shek, commander-in-chief of the army, seized power at gun point. Borodin and Chen Tu-hsiu went along with him. For two confused years Chiang and his reactionary grouping gradually pushed communists and patriots out of key positions. Prominent patriots, particularly those formerly close to Dr. Sun Yat-sen, began to flee or were assassinated.

When the first arrests of communists by Chiang Kai-shek troops began in 1926, Borodin quickly explained it as due to communist “excesses”. He ordered the Chinese communists to restore the united front by giving in to Chiang Kai-shek on all matters. One of Chiang’s first orders was to remove Chou En-lai as political commissar at Whampoa military academy. The Comintern felt sure that Chiang Kai-shek was trustworthy, for they were bribing him with the money, arms and international backing to become head of China. It never occurred to them that Chiang Kai-shek was negotiating for even bigger bribes from British, French, and U.S. imperialism (who were his natural masters).

Chiang Kai-shek out-thought and out-maneuvered Stalin and the Comintern. To buy time he sent his son to Moscow as a hostage. Knowing that the Comintern-Chen clique would swallow any pretense of his loyalty to them, he gave fiery speeches manipulating their own fantasies: “The Communist International is the headquarters of world revolution… We must unite with Russia to overthrow imperialism.” At the Comintern meeting in December 1926, Stalin personally rebuked uneasy Chinese communists. They had reported that the masses, far from feeling liberated by Chiang’s warlord troops, felt “disillusionment” with this new bourgeois army. Stalin replied that the “same thing had happened in the Soviet Union during the civil war”, thus putting the Kuomintang army on the same plane as the Soviet Red Army!

As long as Chiang Kai-shek still needed communist help to conquer the northern warlords and bring all China under his thumb, he tolerated a show of unity. But once he held Nanking and Shanghai, his dictatorship recognized by the Western Powers as the sole legitimate Chinese government, he turned on the revolutionary masses in a savage bloodbath. In Shanghai, communist workers led by Chou En-lai staged an uprising, capturing the police station, railroad station and other strategic points. For three weeks the communists controlled Shanghai, but followed Comintern orders to turn power peacefully over to the advancing army of Chiang Kai-shek.

On April 12, 1927 the bloodbath started. Unprepared and unarmed, the workers, patriots and communists were slaughtered by the thousands in public executions that went on for months. In all the regions held by Chiang Kai-shek and his warlord allies the mass killing went on. Many patriots, especially liberated women, met death only after the most barbaric public tortures. This death count has never been exactly known, but is usually held to be well over one hundred thousand that year.

Facing the most terrible defeat since the crushing of the Taiping army in 1864, the shaken leadership of the Chinese Communist Party met at their Fifth Congress just as the mass repression began. The Comintern-Chen clique decided that their only way out lay in even further concessions to the bourgeoisie. The Shanghai massacres were blamed on Chou En-lai, who was said to have “provoked” Chiang Kai-shek by not completely disarming the workers there. The Kuomintang was offered supreme command of all the workers’ unions and peasant associations if they would spare the Party. As Mao said: “The Central Committee made complete concessions to landlords, gentry, everyone.”

And all during that Spring, as the slaughter went on, peasants had tried to form self-defense militia and fight back. The Comintern-Chen leadership ordered all peasant weapons surrendered to the landlords. The All-China Labor Federation disarmed workers militias. When 20,000 angry peasants and miners in Hunan marched on the provincial capital to avenge the machine-gunning of two hundred unarmed peasant militiamen, the Comintern-Chen clique ordered Mao and the other Hunan leaders to disarm them. The disarmed patriots were then promptly massacred themselves—over 30,000 that Summer in Hunan. On June 4, 1927 the Central Committee answered the pleased for help from Hunan peasant unions with a new directive blaming the killings on poor peasants who had allegedly provoked the Kuomintang armies by “encroachments” on the lands of the rich warlord families. The Comintern-Chen clique went on to order: “To forbid such juvenile actions is an important task of the peasant associations.” Borodin’s last act before being kicked out of China was to try and find Mao Zedong, in order to get him to “restrain” the Hunan peasants some more.

In five years the Comintern had completely betrayed the trust of the Chinese people, had backed counter-revolutionary leadership for Chinese communism, and had failed the test of revolutionary practice. In no way can these errors be placed on Michael Borodin as an individual, although he later admitted: “I was wrong, I did not understand the Chinese Revolution… I made so many mistakes.” The Comintern had sent virtual legions of politically-confused “experts” to China. In a typical case, one Euro-Amerikan was made a Comintern “expert” over the Chinese workers because of his experience as a trade-union organizer in Wisconsin. Another Euro-Amerikan, Earl Browder, was made head of the Comintern’s entire Pan-Pacific Labor Secretariat on the basis of having once organized a local bookkeepers’ union in his office in Kansas City. The Comintern thought that being European and following their orders were enough for being an “expert” over the Chinese Revolution.

The strategic guidelines laid down in Moscow center itself were invariably wrong, usually revolutionary-sounding platitudes that couldn’t be translated into sound practice because they were impractical, mistimed or contradictory. One good example is Stalin’s secret telegram in June 1927, in the middle of the disaster. The telegram ordered the Chinese Communists to push forward the peasant revolution, but use the peasant associations to stop land expropriation (“excesses”) by the masses; the bourgeois leaders must be outvoted on the Central Committee of the Kuomintang by somehow adding “a large number of new peasant and working class leaders”; the Party should quickly gather 70,000 revolutionaries “and organize your own reliable army before it is too late.”

Chinese communists could not spread the peasant revolution by stopping the class struggle against the landlords, obviously had no way of taking over the Kuomintang leadership, and had already lost most of their cadres and active supporters to the repression because the Comintern had spent five years arming the bourgeoisie while disarming the revolutionary masses. It was already “too late” for Stalin’s further meddling.

The right deviation was finally overturned in July 1927, when a new Party Front Committee decided on armed struggle. On August 7, 1927 a provisional Central Committee, including Mao Zedong, ousted Chen Tu-hsiu and confirmed the new policy of revolutionary war. There is no mystery in the ability of the liberation struggle to turn things around while in a difficult position. To save the nation the revolutionary cadres paid heavily in the only resource they had. Peng P’ai, the first great revolutionary leader of the peasant struggle, was captured and executed without breaking. Of those 32 original peasant cadres who founded the communist cell in Mao’s home village of Shaoshan, all gave their lives in the next few years. Mao’s entire family had gone into the revolutionary struggle. Yang Kai-Hui, who was a leading organizer and was married to Mao, held out under torture and was executed. Mao Tse-chien, adopted sister of Mao Zedong, was killed doing underground work in 1929. Both of Mao’s brothers, Mao Tse-min and Mao Tse-chien, had brilliant histories of patriotic work before they were killed by the Kuomintang (in 1935 and 1945 respectively). One brother’s son, Mao Chu-hsiung, was adopted by Mao, became a communist guerrilla cadre, was captured in 1945 and buried alive by the Kuomintang. Mao himself was captured in 1927 by landlord soldiers, and barely escaped as he was being taken for execution, ducking bullets as he broke away into the rice fields.

The period between the Nanching uprising of August 1, 1927 and the Long March in 1935 was not only a time of armed struggle, but of continued two-line struggle around political-military questions. Nor had false internationalism been finally laid to rest. It was in this period that Chinese communism, under the leadership of Mao Zedong, worked out the strategic and tactical answers that led to liberation, finding their “center of gravity” in the armed struggle.

Even though the central Red Army under Mao Zedong’s political leadership had worked out a sound political-military line, these views for some years were only a minority within the revolution. Mao’s new policies were not welcomed by the established leadership. And the Comintern, although publicly praising Mao as a military leader, kept up their disruptive meddling, determined to run the Chinese nation. While the communist cadres and the peasants were fighting to build the Red Power in the countryside, even in the revolutionary low ebb, the Comintern directive to the Chinese Communist Party of June 7, 1929 said:

“...our tactics in the countryside should correspond to the work of the Party in winning over the urban proletariat in the process of its day-to-day economic struggles. It is not at all necessary to begin the peasant movement immediately with calls for carrying out an agrarian revolution, with guerrilla warfare and uprisings.”

Even after the Red Army had built liberated zones and proved the soundness of the Mao line, the Comintern was still discouraging. The Comintern directive in October 1929 defined “all these peasant activities” as only “an important side-effect in the revolutionary wave”. In the name of internationalism the Comintern was undermining what was then the most important communist advance in the world struggle.

Mao had once again been removed from the Central Committee (and even the Province Committee) after 1927. From 1927 to 1935 there were a series of “Left” deviations, under different Party leaders, which were by no means identical but had certain features in common. They tended to be militarily adventuristic; they tended to view the oppressed masses as only a resource to be exploited instead of correctly seeing them as the element of change; they did not unite the nation correctly in a liberation front. These “Left” deviations had led the armed struggle up to and over the brink of disaster.

By 1930 the Comintern center in Moscow was impatient to once again take over total control of the struggle in China. The incumbent Chinese Party leader was removed by the simple method of ordering him to Moscow for an inquiry, and then detaining him there for “education” for 15 years! In January 1931, a special Comintern-trained faction seized the leadership of the revolution. It was headed by new Party Secretary-General Wang Ming, foremost among the group of Chinese “returned students” from Russia (who are ironically known in Chinese history as “the 28 Bolsheviks”).

Wang Ming was a landlord’s son, a former student at Shanghai University, who joined the Chinese Communist Party in 1925 while studying at the Sun Yat-sen University in Moscow. He became a translator for the Comintern. The was the man, with no ties to the masses and without so much as one hour’s experience in the real struggle of the nation, that the Comintern shoved in as the would-be leader of the Chinese people. Wang Ming’s faction called a partial meeting of the Central Committee in Shanghai, without notifying Mao, Chu Teh or other guerilla leaders, and voted themselves in. The Comintern backed this clearly illegal coup. Again, Mao and the revolutionary line were in the minority.

The years of the Wang Ming line (the “Third ‘Left’ Deviation”) were a great disaster for the Chinese people. Perhaps the worst damage might have been avoided had the Wang Ming leadership confined itself to Shanghai and the other big cities, throwing cadres away in periodic “city-taking” adventures. But by the late Summer of 1931 the repression in Shanghai was closing in on the Party leadership. In order to survive most of them had to join the Red Armies in the rural base areas. Wang Ming returned to safety in Moscow.

Mao Zedong, Chu Teh and their communist forces had built a Central Base, a large liberated zone in Kiangsi-Fukien Provinces with a soviet government. The soviet governed three million people, 70% of them poor peasants, over 19,000 square miles (an area equal to the states of Massachusetts and Maryland combined). Unlike earlier bases, the Central Base by 1931 had shown enough strength, when correctly applied, to smash full Kuomintang armies. Three “encirclement and suppression” campaigns, each larger than the last, were smashed by the Red Army in quick succession. In the third campaign Chiang Kai-shek personally commanded 300,000 attacking soldiers, but was still soundly beaten by the Red Army. 10,000 rifles were captured.

The Wang Ming faction took over the Central Base in late 1931 and early 1932, by the simple expedient of declaring it the capital of a newly proclaimed Soviet Republic, a new national government. This paper maneuver effectively put the local base committee out of business, since an all-China government had to be led by the Central Committee itself. Conveniently for Wang Ming, the Russians had just “advised” the Chinese to set up a new national government.

The Comintern-Wang Ming clique were no good at winning battles, no good at building the peoples’ Red power, no good at building the Party, but plenty good at petty-bourgeois intrigue, coups, and takeovers that were parasitic on the work of others. The only fly in their ointment was that they couldn’t avoid elections for the new government—such was the mass recognition of his leadership that Mao was elected Chairman of the Soviet government. Still he was in the minority, and the Comintern-Wang Ming clique were rapidly destroying everything, in particular the political-military line. Mao later summed up:

“But beginning from January 1932… the ‘Left’ opportunists attacked these correct principles, finally abrogated the whole set and instituted a complete set of contrary ‘new principles’ or ‘regular principles’. From then on, the old principles were no longer to be considered as regular but were to be rejected as ‘guerrilla-ism’. The opposition to ‘guerrilla-ism’ reigned for three whole years. Its first stage was military adventurism, in the second it turned into a military conservatism, and, finally, in the third stage it became flight-ism… The new principles were ‘completely Marxist’, while the old had been created by guerrilla units in the mountains, and there was no Marxism in the mountains… And anyone who did not accept these things was to be punished, labelled an opportunist, and so on and so forth.

“Without a doubt these theories and practices were all wrong. They were nothing but subjectivism. Under favorable circumstances this subjectivism manifested itself in petty-bourgeois revolutionary fanaticism and impetuosity, but in times of adversity, as the situation worsened, it changed successively into desperate recklessness, conservatism and flight-ism. They were the theories and practices of hotheads and ignoramuses; they did not have the slightest flavor of Marxism about them; they were anti-Marxist.”

The Wang Ming leadership set up a security program, in which suspects would be eliminated on the spot. Many good revolutionaries were purged (Mao had all such victims restored posthumously to the Party’s rolls after 1945). Mao himself was gradually stripped of all his posts save his elected position as Chairman. His connection to the Army was severed at the Ningtu conference of August 1932. At the same time a new nationalist groundswell had been sweeping China. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931 had shown that Japanese imperialism intended to be master over all China. Mao, as Chairman of the Soviet government, and Chu Teh, as commander-in-chief of the Red Army, signed a declaration of war against Japan. Mao’s program for a new patriotic united front, which later was to prove to be the means by which communists could unit the nation behind their leadership, was rejected. The Comintern-Wang Ming clique attacked Mao’s “nationalism”.

The final mockery of the Chinese peoples’ armed struggle came in early 1933, when a Comintern military expert arrived to take over strategic command of the Red Army from Mao. He was Otto Braun, who used the Chinese alias “Li Teh”. Braun knew nothing about China and nothing about warfare. He was not even a soldier, although the Comintern had given him a military course before sending him to China. Any ignorant European was superior to Mao, in the eyes of false internationalism. And now the Comintern-Wang Ming clique could take full hold of the army, with the visible presence of a big European expert to endorse their claim for leadership.

Otto Braun became the head of a new Military Commission, which included Chu Teh and Chou En-lai, that dictated all military plans. Braun sent the Red divisions off to engage the Kuomintang armies in regular positional warfare. Instead of guerrilla fluidity, Red units were told to dig trenches and fight to the last man before giving up one inch of ground. Instead of Mao’s policy of concentrating superior strength to surprise the enemy with locally superior forces, the new Braun policy was to split up and fight in all directions, with each smaller Red unit expected to confront enemy forces up to ten times its size (under the slogan: “pit one against ten, pit ten against a hundred”).

By September 1934 the immobilized Red Army was suffering defeat after defeat, as the Soviet area choked within the closing ring of Chiang Kai-shek’s fifth “encirclement and suppression” campaign. Panicked, Otto Braun and the rest of the Comintern-Wang Ming clique decided to abandon the Central Base and break out for another base area (which had, in fact, already fallen to Chiang Kai-shek’s armies). Although, as Mao pointed out, the Kiangsi-Fukien base would still hold out for months, giving the Red Army precious time for rest, planning and preparing for the extended Winter march, Otto Braun was too panicked to wait. In October 1934, on a week’s notice, half of the Red Army moved out, 120,000 soldiers and cadre without destination, a military plan, winter clothing or adequate food. 8,000 porters were also taken. The Comintern-Wang Ming clique, used to playing at bureaucracy, had the soldiers and peasants carry government files, furniture, machinery, and all the other trappings. Mao sarcastically called this the “house-moving operation”. That confused flightism was the beginning of the famous Long March.

Otto Braun aimed the bulky columns of the Red Army straight at the encircling Kuomintang fortifications. 25,000 Red soldiers died in the breakout. Pursued constantly and strafed from airplanes, the huge Red army slowly marched day and night. At the Hsiang River Otto Braun ordered the Army to clumsily cross under the direct fire of a Kuomintang army. There 30,000 Red soldiers, cadre, and patriots fell in the seven day long crossing. Ninety percent of the Red Army had been lost—killed, captured, wounded and left behind, or dispersed. Over nine out of ten Party cadres had gone as well. The largest liberated area the Party had yet seen, with three million peasants and workers, had been lost. These were bitter fruits of false internationalism, of “international” meddling that propped up “hotheads and ignoramuses” who were unfit to save the Nation.

Mao writes: “It was not until the Central Committee held the enlarged meeting of the Political Bureau at Tsunyi, Kweichow Province, in January 1935 that this wrong line was declared bankrupt and the correctness of the old line reaffirmed. But at what a cost!” At the conference Chou En-lai criticized himself for having gone along on the Military Committee with Otto Braun, and moved that Mao take the leadership of the Revolution: “He has been right all the time and we should listen to him.” The Conference declared: “the Chinese Soviet resolution, because of its deep historical roots, cannot be defeated or destroyed… The Party has bravely exposed its own mistakes. It has educated itself through them.”

Mao explained to the 30,000 surviving soldiers and cadre at the Tsunyi why the “Left” deviation military policies were wrong, analyzed their recent struggles. Most importantly, he explained that the Long March had a new objective. Not simple flight or personal survival, but to march to the far Northwest to save the Chinese nation, to found a new center for all patriotic resistance to the foreign invaders. Their new destination would become Yenan. The rest we know. The two-line struggle still went on, of course, although under qualitatively changed conditions.

We may ask why the correct revolutionary line was a minority in the Revolution for thirteen years? Why even obvious blunders and repeated military defeats were endured for so long by the ranks of the liberation struggle? We must keep in mind that people grow up under imperialism. Even the oppressed are used to believing in others, and not themselves. Even the rebellious are awed by the bourgeois way of doing things, and are habituated to the yoke of leaders who reflect this. Many soldiers and cadre felt that all those highly-placed leaders, with big reputations and similar ideas, must be right. Who was this Mao Zedong anyway, with his ragged clothes and unfamiliar ideas that weren’t like anyone else’s? When the correct revolutionary line takes root among the masses it becomes a material force, a great human storm that can topple Pharaoh and build a new Nation—but this is not a casual or an easy thing to accomplish.

False internationalism took advantage of this, and took advantage of the genuine internationalism and respect the Chinese people had for the Russian Revolution. The general line of Chinese communism has been to lay no public blame for the errors on anyone but themselves. After all, if some Chinese communists allowed foreigners, no matter how well-meaning or important, to use them against their Revolution, then the main problem is on the Chinese side. Still, the full truth has never been a secret. Much later Mao wrote:

“Stalin did a number of wrong things in connection with China. The ‘left’ adventurism pursued by Wang Ming in the latter part of the Second Revolutionary Civil War Period and his Right opportunism in the early days of the War of Resistance Against Japan can both be traced to Stalin. At the time of the War of Liberation, Stalin at first wouldn’t let us press on with the revolution, maintaining that if civil war flared up, the Chinese nation ran the risk of destroying itself. Then when fighting did erupt, he took us half seriously, half skeptically.”(5)

When the Comintern formally dissolved in 1943, Mao Zedong and his comrades were already at that point; they had long since determined that the Revolution could only survive by ending “such meddling in our affairs”. Most particularly by confused revolutionaries or would-be revolutionaries of other nations. If Chinese communism had not conquered false internationalism they would have been destroyed, root and branch.

Our criticism of the Comintern as an experiment in internationalism is not about errors of judgment. The relationship itself was incorrect in ignoring national distinctions between oppressor and oppressed nations, in ignoring the inescapable duty of each revolutionary movement to struggle out its own answers, reflecting the particularities of its own national situation, and in ignoring the right of each people to demand that its revolutionary leadership be held accountable to it. In other words, self-reliance.

We should never forget that false internationalism promotes political corruption, inevitably shielding slaving attitudes. What kind of contempt for their own people did the Wang Mings have, that they would promote the slavish notion that in all the many tens of thousands of Red commanders, soldiers and cadre—communists who had been tested and remolded in the great furnace of Peoples War—there was not one Chinese comrade who could do the job given to Otto Braun?

False internationalism is not outside the oppressed nation, but is within. It actually divides the oppressed nation, shielding false leaders while subtly promoting the slavish attitudes of the oppressor. This was the lesson of thirteen years of political struggle to find the correct path of armed struggle and national liberation in China.

Footnotes

(1). V.I. LENIN, “Preliminary Draft of Thesis on the National and Colonial Questions”, (June 5, 1920), Lenin on the National and Colonial Questions, Three Articles, Peking, 1966, p. 23.

(2). JAMES PINCKNEY HARRISON, The Endless War, Fifty Years of Struggle in Vietnam, N.Y., 1982, p. 67.

(3). General account of development of Chinese Revolution and Comintern in 1923-35 period drawn from:

HAN SUYIN, The Morning Deluge, Mao Tse-Tung and the Chinese Revolution 1893-1954, Boston, 1972.

AGNES SMEDLEY, The Great Road, N.Y., 1956.

STUART SCHRAM, Mao Tse-Tung, Baltimore, 1967.

HELLEN FOSTER SNOW, The Chinese Communists, Sketches and Autobiographies of the Old Guard, Westport, 1972.

EDGAR SNOW, Red Star Over China, N.Y., 1938.

JOHN E. RUE, Mao Tse-Tung in Opposition 1927-1935, Stanford, 1966.

E.H. CARR, The Interregnum 1923-1924, Baltimore, 1969.

(4). AGNES SMEDLEY, The Great Road, N.Y., 1956, p. 148.

(5). MAO TSETUNG, “On the Ten Major Relationships”, Peking Review, Jan. 1, 1977.