Opportunism and oppressor nation chauvinism spread within the Comintern. This repressed bourgeois ideology still living on within its opposite, the new world revolution. Thus, the betrayal of New Afrikans during the 1930s within the U.S. Empire was not their problem alone, but reflected a worldwide problem. The Comintern itself had an incorrect system of “brother” parties, in which oppressor nation communists would “assist and even supervise the communists in “their” colonies. Similarly, in settler regimes the Comintern maintained the principle of all communists irregardless of nationality being forced into a single party; despite national/political differences, despite different theoretical lines and strategies, and despite the desires of the oppressed. So that in New Afrika, Algeria, Palestine and Azania, oppressed nation communists were a “minority” disciplined within communist parties that were majority European settlers. That this led to abuses can well be understood today.

“COMMUNISM” VS. LIBERATION

Algeria is the clearest example of this phenomenon, where a false communist party forced through a historic split between nationalist rebellion and communism.(1) The “Algerian Communist Party” (PCA) was created in 1936 out of the Algerian section of the French Communist Party (PCF). Despite its name this party was neither Algerian nor communist. It was a supervised puppet of the French Communist Party, a party that never broke with loyalty to “its” colonial empire. Using arguments of false internationalism, the French Communist Party had supported the involuntary “unity and integrity of greater France from the Antillean Islands up to Madagascar, from Dakar and Casablanca up to Indochina and Oceania” (as its 1944 program for a liberated France said).

This “Algerian Communist Party” (PCA) developed as an actual enemy of Algerian liberation, a primarily French settler party (there were one million French settlers living in Algeria until 1961) with a minority of captive Algerians. During these years an Algerian revolutionary who wanted to join the world communist movement had to submit to the orders of this false party. As late as the end of World War II this “Algerian Communist Party” was still denying that an Algerian nation even existed: “The pseudo nationalist who twaddle about independence forget that the conditions of this independence do not exist. Algeria does not have an economic base, a military force, nor a national identity...There does not exist an ‘Arab Algeria’...”

Both this Party and its oppressor nation “brother” party in France proved where their loyalties were during the great Setif uprising of 1945. On May 8, 1945 the Algerians marched down the main street carrying pro-independence posters and green-and-white Algerian flags. When the French police started shooting at the peaceful march, an uprising broke out and quickly spread across the countryside.

For five days fighting continued. Since the Algerians were largely unarmed, French casualties were limited to 103 killed and 100 wounded. But in the savage French suppression of the uprising some 45,000 Algerians were killed. In the cities French settler lynch mobs took Algerian prisoners out of the jails and killed them. French airforce terror bombing raids destroyed forty Algerian villages. Thousands of unarmed Algerians were shot down in reprisals as French troops restored the colonial order.

In this repression the “Algerian Communist Party” not only backed up the colonial regime’s crimes, but took an active part in them. PCA Secretary-General Amar Ouzegane said: “The organizers of these troubles must be swiftly and pitilessly punished, the instigators of the revolt put in front of the firing squad.” At Guelma, where the settler lynch mobs reached their peak, “Algerian Communist Party” cadres led in the mass slaughter of 700 Arabs. In France L’Humanite, the French Communist Party newspaper, claimed that “only” one hundred Arabs had been killed in all of Algeria, that there had been no repression, and reported the uprising as: “Troublemakers, inspired by Hitler, have staged an armed attack against the population...” We must remember that the French Communist Party was then still part of the French coalition government—the Air Ministry that carried out terror bombings of Arab villages was headed by a French Communist Party leader.

ASIANS UNDER U.S. COMMUNISM

These bitter experiences were not just far-off events, unrelated to the u.s.a. Within the U.S. Empire the Comintern had placed Asian communists under the direct supervision of the settler Communist Party USA. The CPUSA turned Asian revolutionaries away from Asia, ordering them to think as loyal “Americans”. Internationalism was misused to mean an all-embracing “unity” with Euro-Amerikans and their Empire, under the old principle: “All roads lead to Rome.” Asians became isolated from all other anti-colonial struggles, and even from each other. The net effect in this regard of the Comintern’s policies was not more internationalism but far less.

In the U.S. Philippine colony the CPUSA representatives educated a petty-bourgeois leadership for the new communist party, the PKP (Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas). The original “first-line” leadership of the PKP were trade union militants, most notably Crisanto Evangelista (leader of the printers union and the most influential unionist in the country). But their orientation was towards open, legal organizing in the cities. Within two years of the PKP’s founding on 7 November 1930, the party was banned, the “first-line” leadership in prison, and the young communist movement disorganized without central command.

In this condition party cadres were unable to resist when the CPUSA, backed by the full authority of the Communist International, moved to reorganize the PKP’s leadership, membership, structure and political line. Over the next five years the PKP was surgically ripped apart. CPUSA Secretary Earl Browder had been in close touch with Philippine communists since his visit in 1927, when he was head of the Comintern’s Pan-Pacific Trade Union Secretariat. Browder and his lieutenants promoted the careerist, pro-Amerikan clique led by Dr. Vincente Lava to become the secret “second-line” leadership that would take over the party. This began “a singular phenomenon in the entire international communist movement”. For the entire rest of the PKP’s life, some thirty years, leadership was passed on as family property by the Lava brothers: first Vincente Lava, then Jose Lava, and finally Jesus Lava. The re-established Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) that is now leading the revolution has written:

“It was around 1935, however, while the Party was still outlawed by its class enemies, when a considerable number of Party members of petty-bourgeois class status crept into a fluid underground party that was deprived of a definite central leadership and trying to carry on political work, bringing with them their unremolded petty-bourgeois and bourgeois ideas. At the helm of this petty-bourgeois element within the Party were those who were greatly influenced by the empiricist and Right opportunist current spread by Browder. At this time, the Communist Party of the Philippines, under the auspices of the Communist International, was assisted by the Communist Party of the USA by seeing to it that cadres like Vincente Lava, who became its leading representative, would carry on Party work.”(2)

In 1936 CPUSA leader James S. Allen came to the Philippines to meet with both puppet Philippine Commonwealth President Quezon and the imprisoned communist leaders. Allen negotiated a conditional release for the PKP leaders. Quezon was a liberal politician, tied to President Roosevelt’s New Deal administration in the U.S. He was glad to release these controversial political prisoners once James S. Allen assured him that the PKP would now be ordered to support the U.S. colonial administration.

This was even made public in 1938, after Allen had personally arranged the merger of the PKP with the peasant-based Socialist Party. The founding statement of the loose merger party “defends the Constitution” of the colonial administration, and explicitly “opposes with all its power any clique, group, circle, faction or party which conspires or acts to subvert, undermine, weaken or overthrow any or all institutions of Philippine democracy.”(4) Once puppet Commonwealth President Quezon saw how well the PKP had betrayed the masses, he met with James S. Allen and granted the PKP leaders the full pardon that the CPUSA publicly begged him for.

By turning their faces toward New York and Washington, by conducting politics as taught by the settler CPUSA, the Philippine communist leaders had turned their backs on their own people. The PKP became even more preoccupied with parliamentary elections, liberal alliances, and petty-bourgeois civil liberties committees in Manila and the other cities. Although they lived in a desperately poor peasant country, the PKP played at the reform politics of the imperialist metropolis. We can’t overlook the fact that the CPUSA didn’t create the petty-bourgeois Philippine misleaders. It simply found them, like water finds its own level. False internationalism once again is shown to be an alliance between petty-bourgeois elements in both the oppressor nation and the oppressed nation. And that early Philippine communism was vulnerable to it because of its own internal contradictions, its own lack of science in concretizing socialism to its particular national-historical situation.

Throughout those years of the 1920s and 1930s the peasant masses, suffering under the lash of feudalism and colonialism, simmered with revolution. Armed peasant rebellions broke out time after time. The Tayug uprising of 1931, which took place two weeks after the founding of the party, ran its course without the PKP even bothering to relate to it. So when World War II began the PKP was unprepared, attempting to carry out legal political life in the capital city under the conditions of Japanese invasion! Once again the “first-line” leadership were easily arrested. The imperialist war forced the reluctant PKP into armed struggle. Although in later years the PKP went on to try guerrilla warfare, it was never able to shake off the leadership and class orientation fostered during the years of Comintern-CPUSA intervention. It died in the 1950s.

When the communist movement went through rectification in the late 1960s to re-establish a new Party, these old betrayals were specifically condemned. And the new Party has always firmly insisted that while their liberation struggle must be part of the international united front against imperialism, that only the Filipino people shall determine the destiny of the Philippine nation.

In the continental U.S. Empire this intervention was partially masked by integrationism. Still it is only when we examine this factor that long unanswered questions can be finally dealt with. When Japanese-Amerikans were ordered to the U.S. concentration camps in 1942, they were politically unprepared—and appeared to be alone and without allies. Chinese, Filipino, Chicano-Mexicano, Native Amerikan, Black and Puerto Rican revolutionaries were all unable to unite in struggle with them. Many Japanese-Amerikans asked then what internationalism meant if no one would fight in their defense? No one could aid them, because they had no independent strategy of struggle to protect their community. They had nothing of their own for people to unite with.

Yet, Japanese revolutionaries had a long tradition of internationalism in the U.S. Even before the Russian Revolution, Japanese who learned about socialist ideas while laboring in the U.S. and then returned to Japan to struggle, tried to establish ties of friendship with U.S. workers. Japanese militants worked and organized alongside Mexican and Filipino workers in the fields. While Sen Katayama is well known in communist history as the founder of Japanese communism, few remember that he was educated in the Black Nation here as a divinity student at Fisk College. In fact, when the nationalist poet Claude McKay was about to be barred from the 1922 Comintern 4th Congress in Moscow (due to the hostility of the official CPUSA delegation), he called on his old friend Katayama for help.

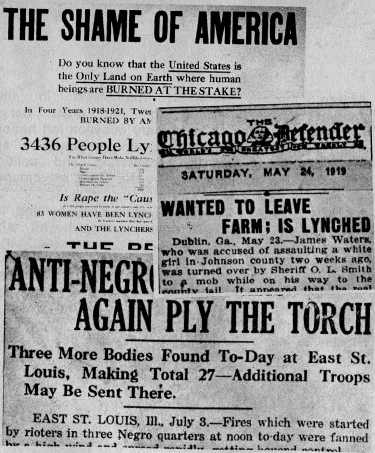

McKay had emigrated to Harlem from rural Jamaica, where he had grown up, seeking to become a writer. At first he wrote while working as a Pullman porter. Soon McKay became a well-known editor and writer for radical journals. He poem “If We Must Die” (“If we must die—let it not be like hogs”), written in fury during the 1919 “race riots”, is still famous today. McKay and Katayama had met in New York City, and had spent many evenings discussing politics together. By 1922, when McKay had arrived in Moscow, Sen Katayama was in his sixties and permanently working in Moscow as a member of the Presidium of the Communist International (and a colonel in the Red Army). Katayama quickly arranged with the Bolshevik leadership for McKay to become a special guest of the Soviet peoples. The Euro-Amerikan CPUSA leadership had been accusing the independent-minded McKay of being a spy in order to get rid of him. Those settlers couldn’t understand how a nationalist poet could call on an Asian communist leader as a comrade and personal friend.(5)

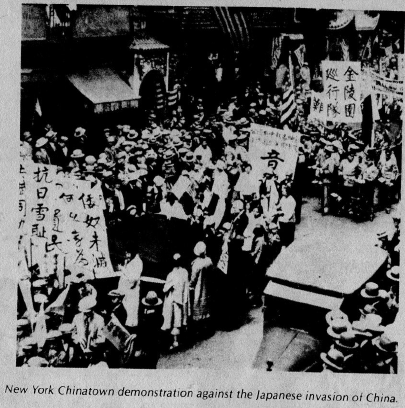

During the 1930s Japanese and Japanese-Amerikan communists in the U.S. tried to meet their internationalist duty, not only in the union drives in canneries and sugar cane fields, but in opposing Japanese imperialism’s invasion of China. Yet in 1942 they were unprepared to defend themselves, and without allies.

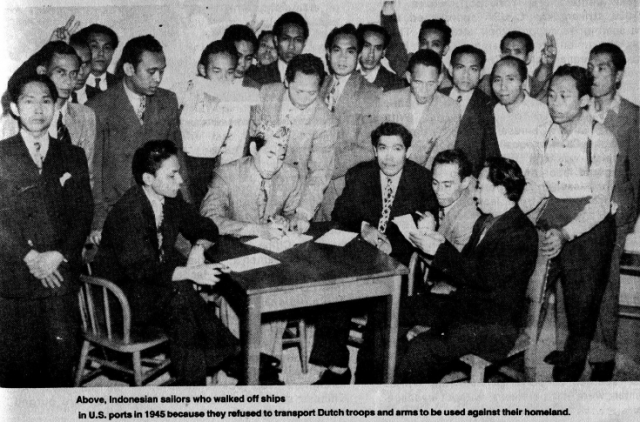

To see what happened we should understand that other Asians here also found themselves suddenly isolated when under attack by imperialism. In 1936-37 the CIO’s National Maritime Union (NMU) found itself locked in a long, difficult strike that would decide the unionization of East Coast shipping. Euro-Amerikan unionists alone were not able to idle all the ships. So the NMU had to recruit colonial sailors as allies. Led by Ferdinand Smith, a Jamaican communist, some 20,000 New Afrikan workers (primarily in the South) agreed to join the strike if the NMU would finally end the traditional Jim Crow conditions in shipping.(6)

In the strike center, New York port, where the NMU had 10,000 strikers, the CPUSA approached the 3,000 Chinese seamen to support their struggle. They agreed to join the union on the same basis as New Afrikans, demanding equal rights. Chinese seamen on U.S. ships were by custom only paid 3.4 of “white man’s pay”, and limited to being waiters and cooks. Customarily half their pay was kept by the company until discharge, to guarantee “good behavior”. With the victory of the strike Chinese seamen won the formal support of the CIO for equal jobs and pay. Once key issue of theirs was the right of shore leave. Chinese seamen could labor on U.S. cargo ships, but could not take shore leave in U.S. ports. The Chinese Exclusion Laws forbid them from leaving their ships while docked in U.S. territory.(7)

Paradoxically the victory of the NMU union drive—which had been led by Communist Party USA—left the Chinese seamen even more isolated. In 1936 Congress passed a bill subsidizing the shipping industry, giving companies high subsidies to carry U.S. mail. At the request of the Euro-Amerikan trade unions, the legislation carried with it the stipulation that no foreign seamen could be employed. This was directly aimed at the Chinese. So in 1937, when the new legislation took effect, U.S. ships fired and abandoned Chinese seamen at ports all over the world. Often the seamen were left penniless, without passage back to China.

In New York Harbon Chinese sailors on the Presidents Line ships S.S. Taft and S.S. Polk began an onboard sit-down strike. They were demanding their jobs back, with six months severance pay and far back to China if dismissed. The workers formed the Chinese Seamen’s Patriotic Association. The Euro-Amerikan communist leaders of the NMU said that they sympathized with their one-time Chinese allies. The National Maritime Union did pressure the company to give the fired Chinese workers severance pay, so that they could buy passage out. This small concession was made.(8) But the Euro-Amerikan communist told their former Chinese allies that the victorious union, which was “American”, couldn’t help foreigners keep jobs in violation of the U.S. laws. All Chinese seamen without U.S. citizenship were purged from the industry.*

* Later, high maritime casualty rates in war zones during World War II opened the door to some Chinese employment on U.S. ships.

But the “Chinese Problem” could not be swept out of U.S. ports so easily. Thousands of Chinese worked on the ships of other nations, particularly of the British Empire. On British ships the Chinese were worked almost as slaves, beaten, ill-fed and often not paid. In 1942 Chinese workers on British ships in the port of New York started jumping ship after a British captain shot down and killed one brother, who had declared that he refused to take any more beatings. At the urgent request of the British, the U.S. Immigration Service terrorized N.Y. Chinatown for weeks, raiding homes and restaurants to find the fugitive Chinese seamen. Four hundred Chinese seamen were recaptured by U.S. authorities, and were handed over to the British on the docks. It was a slave hunt.(9)

Through it all the Euro-Amerikan communists in the NMU sympathized publicly, but said that their “American” union could not handle the problems of “foreign” workers on “foreign” ships. In a city where the National Maritime Union had over 10,000 members, this supposedly communist-led union stood by watching with folded hands as Chinese seamen were hunted down like animals. The anti-imperialist union on the British ships, the Chinese Seamen’s Union, was smashed by repression. The last Chinese sailors’ resistance was broken when the British Government announced that any Chinese worker who tried to quit a British ship would be arrested by the U.S. government and sent to be captive military labor in India. Again, the CPUSA and NMU said that as good “American” organizations they couldn’t oppose this.(10)

There were thousands of New Afrikan seamen, with many militants among them, as well as Chinese-Amerikan seamen. There were active communist groups among the Chinese-Amerikans, among Japanese-Amerikans, among Puerto Ricans. Why were those desperate Chinese seamen without allies right in New York City? Because all the colonial communists here were disciplined “minorities” under the direction of the Euro-Amerikan Communist Party USA. The more organized everything became, the more unionized workers were, the more colonial revolutionaries became “united” within the settler CPUSA, the less freedom there was to make genuine alliances. Latino and Asian and New Afrikan only had a relationship through the settler CPUSA. Like separate spokes on a wheel, their “unity” consisted of each of them having a heavy relationship to Euro-Amerikan communists, who were at the center of everything. “All roads lead to Rome.” But none of them had independent relationships to each other or, even more importantly, to their own people. What looked on the surface like lots of internationalism, turned out to really be no internationalism at all.

This was one reason why Japanese-Amerikans had no allies when the concentration camp round-ups began in 1942. Once the treacherous CPUSA decided to support their imprisonment, they naturally blocked other Third-World communists from fighting against the concentration camps. Does this mean that the settler CPUSA bears the main responsibility for the lack of internationalism? Absolutely not. The main responsibility was held by Japanese-Amerikan revolutionaries.

We say that internationalism begins in self-reliance. There is a widespread trend of though that really believes the reverse, that international solidarity is needed to compensate for weakness. This is what Japanese-Amerikan communists (most of them youth with little political education) believed in the 1930s. They thought that their people would be protected by the broad alliances woven by the Communist Party USA; that their small numbers were compensated for by joining the masses of liberal and radical settlers. This illusion was deliberately encouraged by the CPUSA, to be sure. Japanese-Amerikan communists joined the picket lines protesting Japan’s invasion of China, boycotting Japanese silk and demanding an end to scrap iron sales to the Japanese war industry—”Silk Stockings Kill Chinese”. Japanese-Amerikan communists were united with Filipino and Chinese brothers and sisters in building the CIO Cannery Workers Union on the West Coast in 1936-1938. On 11 July 1937 Jack Shirai, a New York restaurant worker, fell in the defense of Madrid.(11) A Japanese-Amerikan revolutionary gave his life to help the Spanish people fight fascism. In doing all this young Japanese-Amerikan communists thought that they were building internationalism. But as the troops herded them into the trains to the camps, they learned the hard way that nothing had been built. Internationalism is not a crutch for beggars, as some U.S. revolutionaries today think it is.

Others could not aid their resistance if it had never been built into a real campaign of struggle. Shamefully, Japanese-Amerikan communism had never prepared to lead any program in their own defense. For years and years, as the storm clouds of U.S.-Japan imperialist war darkened over Asia, as anti-Japanese chauvinism was whipped up by the imperialists, Japanese-Amerikan communism refused to deal with the coming crisis. No plans were made. No organization of political self-defense prepared. Years of possible preparation for the storm had been wasted. Only their own self-reliance, only their own early campaign of resistance, could have provided the basis for real solidarity between them and other peoples.

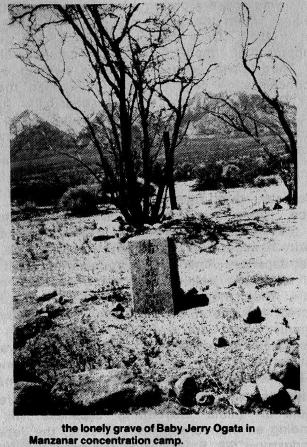

And once they were attacked, the CPUSA ordered the remaining Japanese-Amerikan communists to become collaborators. So in the concentration camps CPUSA “communism” became the ideology of traitors. Those “aka” (radicals) who still followed the CPUSA, together with the pro-imperialist civil rights leaders of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), became open collaborators. In the Manzanar camp the CPUSA members formed the “Manzanar Citizens Federation”, which urged inmates to “prove” their loyalty to the Empire by volunteering to serve in the military and by doing war production labor on camouflage nets and in picking crops. Some CPUSA and JACL collaborators also began acting as informers for the U.S. military police. The opposite tendency in Manzanar was led by the Blood Brothers Organization, an angry, anti-Amerikan youth group known by its “Black Dragon” symbol.

This all came to a showdown in December 1942. The head of the inmates’ Kitchen Workers Union was arrested by G.I.s after he publicly exposed how the Assistant Warden was stealing meat and sugar rationed for the prisoners. His elected replacement was also arrested. That night a crowd of 1,000 angry, shouting Japanese-Amerikans confronted G.I.s at the administration building. The G.I.s began shooting, killing two and seriously wounding eight (those with light injuries were hidden out by the people). After they had escaped the G.I.s, some of the “Black Dragons” decided that it was intolerable to let the informers just walk about. So that night attempts were made to correct the leading CPUSA collaborators. Finally, the U.S. Army had to take the collaborators and their families into protective custody and move them out of the camp, to save their lives.(12)

Those Japanese-Amerikan CPUSA members, who had the heaviest responsibility to lead their people, had failed international communism and themselves. This is the verdict of history. How could other communists aid them in their struggle, when their own communist leaders were supporting the oppressors? The absence of internationalism was their own responsibility first and foremost.

EARLY NEW AFRIKAN COMMUNISM

Oppressed nation communists had two unresolved problems in the 1920s and 1930s. The first was the widespread belief, common until the period of Algeria and Vietnam, that a numerically small oppressed people could not overcome a large oppressor nation. The second was petty-bourgeois ideology, manifested in the stubborn belief that the goal of the struggle was to live a privileged European life, that liberation meant joining imperialism as equals. This petty-bourgeois ideology was the primary problem, causing the inadequate theories of struggle that defeatism fed on. These two errors intertwined to trip up the liberation movements of the 1920s and 1930s in the U.S. Empire. For that matter, they still remained to strongly influence the new revolutionary movements that arose in the 1960s.

The first wave of New Afrikan communists took shape as a tendency within the nationalist movement. Like Marcus Garvey (whom they all knew), many of those early communists were Pan-Afrikanists from the West Indies. Cyril Briggs, the founder of the Afrikan Blood Brotherhood, was from the British colony of Nevis. His close associate, the brilliant agitator Richard Moore, came from Barbados. In the Harlem of 1918-1920 these first communists were active and respected in the community. Briggs had been the editor of Harlem’s leading newspaper, the Amsterdam News, before resigning in 1918 over the publisher’s interference with his anti-war editorials. Brigg’s close friend, the socialist W.A. Domingo, was the first editor of Garvey’s newspaper, the Negro World. Richard Moore was a local representative of the African Times and Orient Review, the ground-breaking Pan-Afrikanist journal published from London by Duse Mohammed (who had been Marcus Garvey’s mentor). Like Mao Zedong and General Chu Teh in China, these early New Afrikan communists came to political awareness within the broad nationalist movement. And they had all been internationalist in their outlook before they became communists.(13)

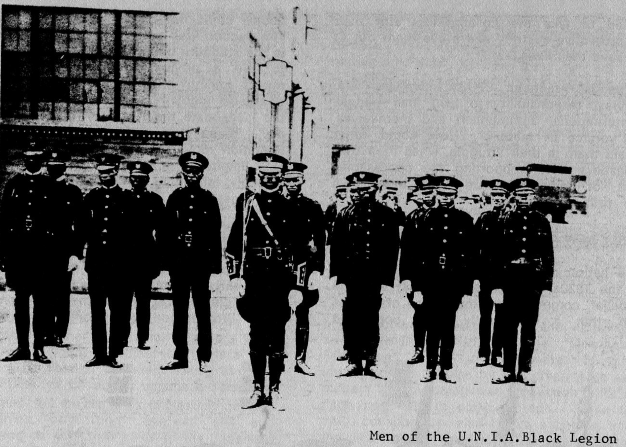

The nationalist movement as a whole, however, was convinced that New Afrikans were too outnumbered and too weak to fight the settler Empire. This belief led Marcus Garvey to react conservatively to the growing political repression of the 1920s. His movement hoped for a friendly or at least a neutral relationship with the U.S. bourgeoisie. The U.N.I.A. attempted to buy time until their pioneers and resources from the Western Hemisphere could return to take over the nation of Liberia, giving them a sovereign land base from which to expand outward across the Afrikan continent. Garvey vainly tried to forestall repression by appearing to go along with U.S. imperialism, even to the point of trying to make peace with the resurgent Ku Klux Klan. While the New Afrikan masses remained nationalist in their sentiments, the inability of the giant Garvey Movement to resolve this primary question left nationalism without a practical program for liberation, and laid the basis for the splintering and political confusion that quickly overcame the broad movement.

New Afrikan communists, while they pushed the necessity for armed self-defense, shared with other nationalist the doubts that their oppressed nation could defeat U.S. imperialism. In 1918 Cyril Briggs founded the Crusader, the militant newspaper that would become the voice of the A.B.B., representing: “TEN MILLION colored people, a nation within a nation, a nationality oppressed and jim-crowed, yet worthy as any other people of a square deal or failing that, a separate political existence.”(14) Briggs as well as Garvey was soon saying that mass repatriation to Afrika was forced on their people by “Necessity”. It was only in the new world upsurge in socialism that Briggs saw the changed conditions that might allow Black people to finally win a just place for themselves in North Amerika. By 1921, Briggs was urging: “Every Negro in the United States should use his vote, and use it fearlessly and intelligently, to strengthen the radical movement, and thus create a deeper schism within the white race in America...”

In Cyril Briggs’ view of 1921, socialist revolution the U.S. oppressor nation would be the only conditions under which “the African question” could be settled here. This was the view that brought Briggs, Moore and the rest of the African Blood Brotherhood into the Communist International. This is an important point. The early New Afrikan communists did not necessarily see an internal force within U.S. settler society capable of redeeming it. Nor were they naive, trusting integrationists. They only united the A.B.B. into the CPUSA because they believed that the revolutionary vision and power of the Bolsheviks would kick Euro-Amerikan leftists into line as allies. In a real sense, those New Afrikan communists felt that they weren’t really joining the U.S. white Left (which they didn’t think too highly of) but the Communist International of Lenin and Stalin. There is a fine but definite line between internationalism, which upholds the necessity for the oppressed and forward-looking peoples of the world to unite, and the error of seeing liberation as coming from external forces and not from yourselves. The A.B.B. leaned heavily on the U.S.S.R. as the supposed answer for the national dilemma faced by New Afrikans. The results were devastating.

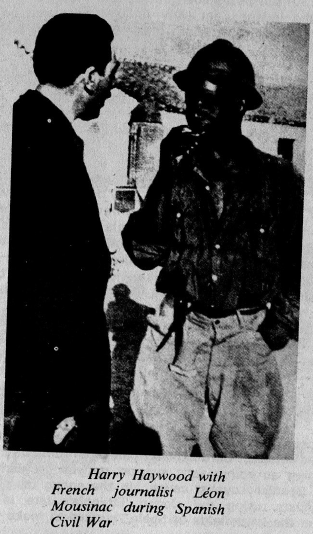

When Black radical Harry Haywood told his older brother, Otto Hall, in 1922 that he too wanted to join the CPUSA, Hall secretly enrolled him in the African Blood Brotherhood instead. That, Hall said, was a temporary measure decided upon by the Black comrades until the CPUSA straightened out the racism in the local Chicago South Side branch. Haywood asked his older brother: “And if you don’t get satisfaction there?” “Well, then there’s the Communist International!” Hall replied. Haywood recalls: “I was properly impressed by his sincerity and by the idea that we could appeal our case to the ‘supreme court’ of international communism, which included such luminaries as the great Lenin.”(15)

The first wave of New Afrikan communists were so vulnerable to false internationalism because they viewed the Bolshevik Comintern as their main ally against the racism of the Euro-Amerikan radicals. Further, they believed that the resulting alliance with Euro-Amerikans was the indispensible precondition for the small Black Nation to fight the U.S. Empire. The results of this political delusion were larger than was first realized. For ten years the full meaning of joining the Comintern was masked, since Briggs, Moore and most of their comrades had little contact with the white Left. Typical was their work in the Harlem Educational Forum and similar socialist ventures in cooperation with other Black radicals. But two important things had happened. Communism was being taken out of the broad nationalist movement. The African Blood Brotherhood was stillborn, within two years of its founding being dissolved into the CPUSA. This meant that the New Afrikan Nation didn’t have self-determination over its own revolutionary forces.

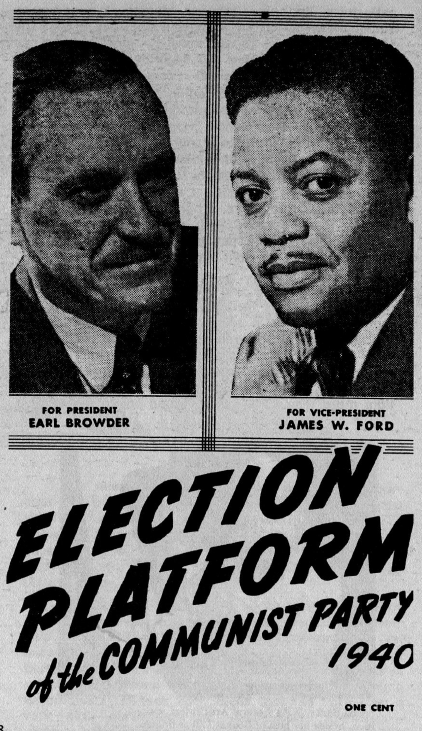

By the early 1930s the settler Communist Party USA was operation on Black communism, ripping out its national revolutionary orientation. Cyril Briggs and Richard Moore, for example, were purged to make way for synthetic Black leaders whose only lifeblood was settler revisionism (James W. Ford Jr. and Harry Haywood became the two best known examples of the latter). Briggs was removed in 1933 from editorship of the Party’s Black newspaper, the Liberator, and shifted out of Harlem to do other Party work. Richard Moore was charged with “petty bourgeois nationalism” in 1934 and removed as national secretary of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights.

Just as in the Philippines, the oppressor nation CPUSA changed the leadership of colonial communists and even the party membership and structure. To suppress the nationalism that always simmered among their Black members, the CPUSA banned any all-Black gatherings. No Black community party unit, work committee, social gathering or even mass organization could take place without Euro-Amerikan CPUSA members in watchful attendance. In 1933 Louis Sass, a Hungarian-Jewish chemist, was made chief administrator of the overall Harlem branch. Increasingly key inner administrative roles within the Party’s Black activities were held by settler intellectuals (just as the Jewish James S. Allen was its main theoretician on Black politics). The Party was worried about a nationalist revolt within its ranks, and crudely dismembered the nationality-based structure that had been built earlier by the first Black communists. Remaining Black CPUSA members became trapped by an “internationalism” in which they were constantly guarded as though they were inmates.

Having tactically united with some of the most brilliant revolutionary nationalists of the period, having built a small political base in the community on the basis of supporting the Black Nation, the settler CPUSA then began to use its disciplined Black followers as puppet political agents to pacify the ghetto.

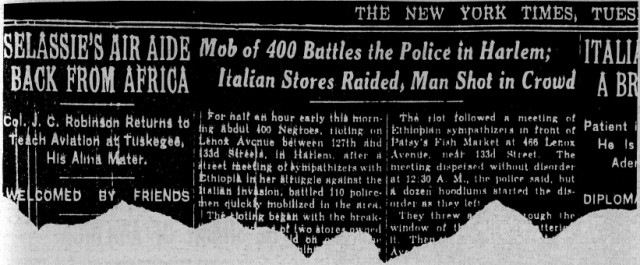

For by 1935, under the impact of the Depression and the threat of Italian invasion of Ethiopia, the New Afrikan community was alive with resurgent nationalism. Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, founder of the NAACP and the most prominent New Afrikan intellectual in the U.S., had stunned the liberal establishment by rapidly moving towards a nationalistic militancy. The violent 1935 uprising on the streets of Harlem was being mirrored in the political evolution of a man who had been the No. 1 symbol of liberal integrationism. In the June 1934 editorial in the Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine, Dr. DuBois called for New Afrikan separatism. In words not dissimilar from those of his old foe Marcus Garvey:

“Instead of sitting, sapped of all initiative and independence; instead of drowning our originality in imitation of mediocre white folks... we have got to renounce a program that always involves humiliating self-stultifying scrambling to crawl somewhere we are not wanted; where we crouch panting like a whipped dog. We have to stop this and learn that on such a program one cannot build manhood. No, by God, stand erect in a mud-puddle and tell the white world to go to Hell, rather than lick boots in a parlour...”(16)

Within the next year DuBois used his position with the NAACP to call for “A Negro Nation within the Nation”. All those forces that had pushed up Dr. DuBois—the Black liberal petty-bourgeoisie and their powerful patrons in the establishment—then rushed to cut Dr. DuBois down. He was ousted from the NAACP leadership, white-listed at the Black colleges, unable to find employment or a forum. This was nothing unusual or unexpected. What was interesting was the fact that the political attack on Dr. DuBois was joined in by the white radicals in and around the CPUSA.

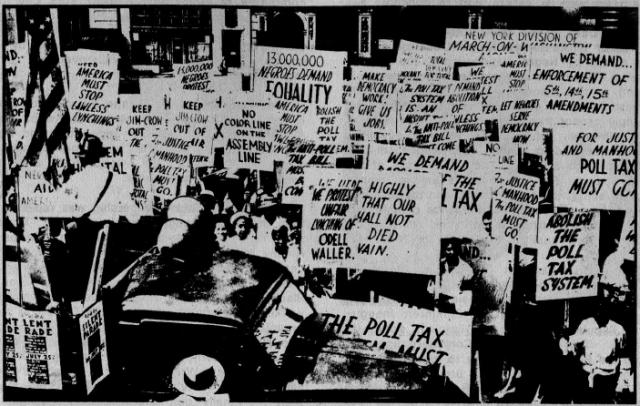

The prominent Nation magazine featured a major article on DuBois in its May 15, 1935 issue. The author was a Euro-Amerikan radical labor journalist, Ben Stolberg. Stolberg quickly linked DuBois’ new nationalist views up with the nationalist mood of the New Afrikan community as a whole; which he described as “jobless, hungry, bewildered, and rapidly finding escape in radical chauvinism.” Stolberg spoke for settler radicalism when he flatly declared that there would be “no Black economy or Black autonomy”. He ended by criticizing New Afrikan people in a threatening way as “a counter-revolutionary force in the American class-struggle”.(17)

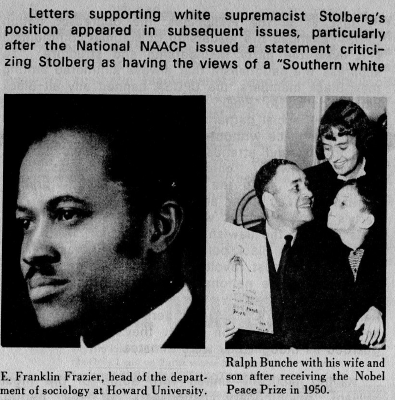

Letters supporting white supremacist Stolberg’s position appeared in subsequent issues, particularly after the National NAACP issued a statement criticizing Stolberg as having the views of a “Southern white bourbon”. Four of the most prestigious Black professors, led by E. Franklin Frazier and Ralph J. Bunche, wrote a letter applauding Stolberg for “a brilliant and sound analysis”. The four closed their letter by saying: “We, Negro teachers at Howard University, subscribe to the same kind of Southern white bourbonism.”(18) The most interesting letter came from the CPUSA, which for years had been denouncing DuBois as one of the “lap dogs at the table of imperialism”. CPUSA representative James S. Allen, their leading theoretician on colonial matters, wrote to assure his fellow settlers that the CPUSA joined ranks against New Afrikan nationalism in the revolutionary crisis:

“Petty-bourgeois Negro leaders (now including Dr. DuBois) and organizations are attempting to divert this upsurge into channels of separatism and segregation. It is precisely against such petty-bourgeois nationalism that the Communist Party fights...”(19)

Stolberg, as well as others, had to concede that nationalism was the growing sentiment of the New Afrikan grass-roots. Even the CPUSA admitted this. When a reader wrote to the Negro Liberator asking: “What is meant by Negro Nationalism?”, the printed answer was: “Negro Nationalism (or petty-bourgeois nationalism) is the theory that the solution to the Negro question lies in one race fighting another... The Negro people cannot free themselves without fighting in unity with their white allies for full equality... Among the outstanding leaders of nationalism are Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. DuBois. The tasks of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights are the expose these leaders and at the same time to win the rank and file Negroes, who are under the influence of nationalism, to a program of struggle with their white fellow toilers for complete equality.” (our emphasis) (20)

The united front against Dr. DuBois showed a growing convergence between the Communist Party USA and the Black petty-bourgeoisie. This took full form after the 7th Congress of the Comintern inaugurated the Popular Front Against Fascism policy in August 1935. The CPUSA, with Comintern approval, interpreted the Popular Front policy to mean that New Afrikan communists should build broad, “interracial” coalitions on a liberal basis, with the goal of full assimilation into White Amerika.

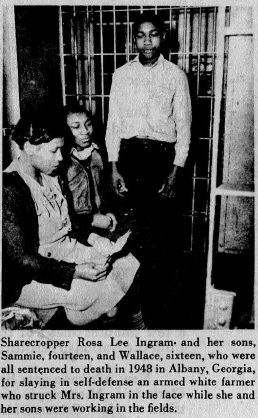

In the Winter of 1935 what was left of the Party’s activity for New Afrikan self-determination was stopped. The CPUSA Central Committee officially shelved the issue itself, meaning that the Party still professed to believe in New Afrikan self-determination but would no longer organize around it. Both the League of Struggle for Negro Rights and the newspaper Negro Liberator were ended. In the South the armed Alabama Sharecroppers Union, which had grown since 1931 to 10,000 members in rural Alabama with 2,500 more in Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia and North Carolina, was dissolved the next October. The CPUSA Central Committee decided that the sharecropper movement was leading toward widespread armed struggle on the National Territory (which was certainly correct), which they didn’t want. A small committee of white men in New York City had the power to order an armed New Afrikan mass organization, fighting for the Land, to give up. The Sharecroppers’ Union had been created by sharecroppers themselves, but was overcome by false internationalism.

Now we can return to the question of the mass Ethiopian solidarity movement that swept the New Afrikan Nation in 1935-36, and understand how the CPUSA’s treacherous line could prevail within the movement despite the nationalist and militant sentiments at the grassroots.

The Party’s Black membership was rapidly growing then, but also changing in class terms. There were still many working class nationalist members like Audley Moore, the famous woman organizer who had come to Harlem radicalism from the Garvey Movement in New Orleans. Increasingly, however, many Black members were professionals, white collar workers or students who saw the CPUSA as the only organization that would help them get advancement into White Amerika. Many of those who felt otherwise about their own goals were quitting. The young novelist Richard Wright, unable to match his “individuality” to the Party’s program, almost left the Party then (he finally quit later in 1942). Wright turned down the offer of a European trip and possible promotion made to hm as a bribe by Harry Haywood, a Black Central Committee member. He had noticed that the Party’s air of crude opportunism that so disgusted him attracted many others: “...as I was losing touch with the Party, may other young Negroes of the South Side were entering it for the first time. The expansion of the Party’s activities under the People’s Front policy offered many opportunities to young Negroes who, because of race and status, had led cramped lives. The invitation to go to Switzerland as a youth delegate, which I had refused, was accepted by young Negro who had fought the Communist Party and all its ideas until he had seen a chance to take a trip to Europe.”(21)

An academic study of the CPUSA in Harlem brings out how important that united front with settler radicals became to the Black petty-bourgeoisie:

“Between 1936 and 1939, the Communist Party emerged as an important focal point of political and cultural activity by Harlem intellectuals. ‘My memory and knowledge’, Party organizer Howard Johnson recalls, ‘is that 75% of black cultural figures had Party membership or maintained regular meaningful contact with the Party.’ Harlem critics of the Party spoke bitterly of the Party dominance of the black intelligentsia and feared they would use this to ‘capture the entire Negro group’. ‘Most of the Negro intellectuals’, Claude McKay wrote, ‘were directly or indirectly hypnotized by the propaganda of the Popular Front’...

.......

“...The new Party strategy called for the incorporation of the entire black community into antifascist alliances with white liberals and radicals, and it viewed the black intelligensia as a pivotal group in its quest for ‘sustained and fraternal cooperation’ with the most powerful groups in black life—the NAACP, the Urban League, and the black church.

“The Popular Front Party’s success among Harlem intellectuals, however, whether measured in membership of political influence, proportionately far exceeded its impact on Harlem’s working class. Abner Berry and Howard Johnson, important Party leaders in the period (Johnson was a leader of the Harlem Young Communists League), both recall that the Party had a very high percentage of middle-class members—perhaps half—in a community where the overwhelming majority of the population was working class and poor. Although articles in the Party’s social composition, the one Party branch in Harlem consistently singled out for praise during the Popular Front era, the Milton Herndon branch, was localed in ‘Sugar Hill’, probably Harlem’s wealthiest neighborhood. The set of symbols and affinities that marked Popular Front politics in Harlem—linking the cause of Ethiopia with that of China and Loyalist Spain; identifying the persecution of Jews in Germany with that of blacks in the United States; viewing the New Deal and the labor movement as harbingers of black progress—had more weight among black doctors than they did among black domestics, or among parishioners of St. Philip’s than worshippers in storefront churches.

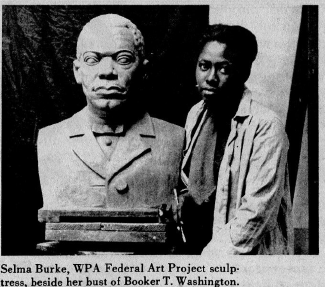

“...Between 1935 and 1937, white-collar employment opportunities for Harlem blacks expanded enormously, parly as a result of liberal policies of the LaGuardia and Roosevelt administrations, and partly as a result of protests against discrimination led by left-wing unions and Harlem community groups. In the Emergency Relief Bureau, a center of leftist agitation, more than 1,100 blacks found employment, most in skilled positions, and thousands more received jobs on WPA projects set up during 1935 and 1936. Although most WPA jobs were in blue-collar fields—e.g., sewing or construction—the WPA represented a special boon for educated Harlemites: more than 350 found employment on a theatre project as actors, directors, and designers; other found jobs as writers and researchers and teachers on adult education programs; musicians and artists found employment in their specialties; and WPA health centers hired black doctors and nurses. Many Negro WPA employees had ‘the best jobs they’ve ever had in their lives’, the Amsterdam News declared. ‘Thousands of Negro clerks and other white collar relief workers found the kind of employment they are trained for.’

“This expansion of opportunities in government employment, coming at a time of stagnation and decline in black business enterprise, tended to undermine the prestige of strategies emphasizing black self-sufficiency and give credence to those emphasizing interracial alliances...

“These positive experiences with the left, along with a profusion of new opportunities, gave educated blacks something of a buffer against nationalist ideologies which had a hold among less privileged sectors of Harlem’s population. As the economic crisis persisted, and Harlem’s poor fell into nearly total dependency on the relief system, street speakers preaching variations on Garvey’s message expanded their popular following. Embittered by their isolation from positions of power and near-exclusion from the Harlem media, they combined shrewd critiques of interracialism with raw agitation of prejudice against Italians and Jews. Admirers of Japan, the first ‘colored nation’ to become a world power, they bitterly rejected any internationalism which lacked a racial component and urged Harlemites to ‘think black, talk black, act black, and see black’.

“The pessimism inherent in this vision had deep roots in Afro-American culture—as Garvey’s appeal demonstrated—but it failed to strike a chord among an upwardly mobile black intelligensia and white-collar group that saw its position in American life materially improving and perceived antifascism as a worldview which gave legitimacy to their aspirations.”(22)

The Afrikan elite supported the CPUSA’s take-over of the Ethiopian solidarity movement because it also expressed their own class views. After the Pittsburgh Courier reported from Addis Ababa that the Ethiopian military was open to New Afrikan volunteers, in particular those with technical skills, the newspaper’s owner announced that the Volunteer Movement was illegal. The U.S. Government ordered the Ethiopian Consul-General to stop all recruiting of volunteers. Robert L. Vann, the Courier’s owner, was also an Assistant to the U.S. Attorney-General.(23) In an “international” coalition the “Black Cabinet” and settler radicals were standing together against the nationalist upsurge in the streets.

These were class contradictions within the oppressed nation. Liberal integrationist leaders such as the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. and the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins had, after all, spent years in bitter conflict with the nationalists. After Powell had used the pulpit of his powerful Abyssinian Baptist Church in 1933 to criticize the illegal tactics of the nationalist “Jobs for Negroes Movement”, nationalist Sufi Abdul Hammid set up his soapbox right outside the church. Crowds would gather as he damed the Rev. Powell as a degenerate taken up with alcoholism and sex. The nationalists were attempting to follow Marcus Garvey’s vision in using Afrikan buying power and small retail trade as building blocks toward a future separate Afrikan economy. To them the boycott and displacement of Italian merchants was important—even a pushcart “business” can be a step upward to someone who has nothing. There was a nationalist ideological commitment to the creation of a commercial New Afrikan petty-bourgeoisie, and they had close ties to the independent New Afrikan merchants who shared their hostility to both white business and white unions.(24)

Black intellectuals openly scored these limited ghetto ambitions. Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. sneered at them in his column in the Amsterdam News: “Give the Italian haters Antonio’s fish cart, Tony’s ice business, and Patsy’s fruit stand and they’ll forget all about Haile Selassie.” To the college-educated Black professionals running a cramped food stand or a little shoe shop would only be a come-down. They as a class could have far different social goals than self-educated street organizers. Black professionals wanted to get their “rightful place” in the mainstream of the settler Empire’s institutions—in government agencies, medical centers, the big corporations. The CPUSA’s liberal integrationism backed with mass protests fit their class politics. So when the Black white-collar petty-bourgeoisie got a chance to help liquidate Afrikan solidarity into a fashionable Euro-Amerikan cause, they became intoxicated with this false internationalism. One history recounts this strange episode of Black professionals pretending to be European:

“Because this perspective was widely shared among educated blacks, Communists had little difficulty in developing an enthusiastic support network in Harlem for the Spanish Loyalist cause. In the spring of 1937, Communists, using the slogan ‘Ethiopia’s fate is at stake in the battlefields of Spain’, worked to make the Spanish Civil War the preeminent cause for internationally-minded blacks. They encouraged blacks to serve in the International Brigades as soldiers and medical workers and to contribute money and medical supplies which they had collected for Ethiopia to the Spanish government. ‘The material aid which they could not give to the Land of the Ethiopians,’ William Patterson wrote, ‘separated as they were thousands of miles and innumerable difficulties imposed by... capitalist governments, can be given through Spain.’

“Nationalist leaders bitterly attacked this initiative, but many black intellectuals adopted the Spanish cause with great fervor. Several nurses and doctors active in United Aid for Ethiopia (including Dr. Arnold Donawa, the former head of Howard University dental school) volunteered for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade; Harlem churches and professional organizations sponsored rallies for the Loyalist cause; and black relief workers and doctors raised enough funds to send a fully equipped ambulance for Spain. Two black who died in Spain—Alonzo Watson and Milton Herndon—were honored with memorial services at leading Harlem churches (St. James Presbyterian and Abyssinian Baptist) and torchlight parades through the community. A Carnegie Hall Concert for Spain, sponsored by a Harlem and Musicians’ Committee for Spanish Democracy, featured people like Cab Calloway, Fats Waller, and Count Basie, and a dinner in honor of Salaria Kee, a black nurse who served in Spain, drew virtually the entire black nursing staff from Harlem and Lincoln hospitals.

“By 1938, support for Spain had assumed an almost fashionable air, becoming a symbol of sophistication and political awareness among Harlem’s intelligentsia. ‘There was much speech making, singing, and dancing for Spain,’ George Streator recalled. ‘Spanish freedom and Negro freedom were made to be synonymous.”(25)

This class contradiction took place within the larger frame-work of Empire and neo-colonialism. Popular Front strategy by the CPUSA was very effective at not only splitting a New Afrikan united front, but at playing off nationalists against each other. Captain A.L. King of the U.N.I.A. was persuaded to join the CPUSA’s joint campaign against other nationalists. Communists got a suspicious U.N.I.A. leader to address a meeting of their Italian Workers Club in 1935. Instead of the open animosity he expected, the nationalist leader was greeted by the Italian communist audience with warm applause and donations of money. Touched by this unexpected show of respect, the U.N.I.A. leader was won over to being a CPUSA ally. Even within the nationalist movement there were those who didn’t reject Babylong as a thing, but only opposed it tactically because they themselves were not accepted by the oppressor society. Many nationalists were successfully reached by the CPUSA.

Essentially the New Afrikan National Movement, which had made great strides, was hijacked by a coalition of petty-bourgeois Euro-Amerikans and petty-bourgeois Blacks, who “recognized” each other as the joint leadership. The New Afrikan masses were frozen out, allowed no voice in their destiny. At a time when the New Afrikan proletariat was growing politically, the effect was to force them as a class out of the movement. There was a movement program mainly for Black intellectuals, white-collar workers and professionals, which advanced their narrow class interests. There was an AFL-CIO industrial trade union program, of a purely economic nature, for that small percentage of New Afrikan urban workers who worked with settlers in major industry—steel, auto, chemical, rubber, etc. In those sectors the CPUSA was attempting to convert the New Afrikan workers into a relatively better-paid, settler-led, labor aristocracy split off from the rest of the New Afrikan proletariat.

But for the majority of the New Afrikan proletariat, unemployed, casual labor, domestics, etc., the movement literally had no program. Nor did it have one for the millions of New Afrikan sharecroppers and farm laborers it had so casually abandoned. The movement simply left the vast majority of its oppressed Nation on the side. Black radicals co-opted by the CPUSA bad come to represent a petty-bourgeois program. The same was true of the nationalist movement, however much it shared the anger of the colonial oppressed.

Claude McKay wrote with bitter rage at that insolent class viewpoint of Black CPUSA officialdom in the ‘30s: “Once I mentioned to Mr. Manning Johnson the fact of hundreds of Negroes working in the innumerable coffee shops, sandwich shops, fish-and-potato shops, Southern-cooking restaurants, etc. in Harlem. Mr. Johnson is a college graduate, an efficient organizer of the Cafeteria Union and prominent in the Communist hierarchy. I said I thought it would help the community if those workers were welded together in a General Union of Negroes or some such organization. But at the places I mentioned Mr. Johnson sneered as stink-pots.

“He was right. These Harlem places cannot be compared to cafeterias downtown. But after all, the whites whom we envy—beating our brains out against the walls of their prejudice—they too began at the bottom.”(26)

The result of pushing the New Afrikan proletariat out of their own national movement, of turning would-be communists into oppressor nation puppets, was easy to see. Blacks started leaving the Communist Party USA and its influence. Even the Black professionals discovered that the settleristic CPUSA was hard to live in. 1936-1938 the Party recruited 2,320 Black in New York, but lost 1,518 Black members. In 1946 Black Party leader Doxy Wilkerson admitted: “Tens of thousands of Negroes who instinctively rejected our illusions remained entirely without our influence. And many thousands of those who entered our ranked failed to find the answers they sought...”(27) The collapse of the New Afrikan Liberation Movement at the end of the ‘30s reflected not lack of mass consciousness but the failure of their leadership.

Footnotes

(1). Information on French revisionism re Algerian liberation drawn from:

KONRAD MELCHERS, “Racism Communism—How the French Communist Party Tried to Sabotage the Algerian Revolution”, Ikwezi, March 1980;

ALASTAIR HORNE, A Savage War of Peace, London, 1977, p. 23-28.

(2). Rectify Errors and Rebuild the Party, Congress of Re-Establishment, Communist Party of the Philippines, Dec. 26, 1968. Published by the Filipino Support Group, London, 1977, p. 13.

(3). ALFREDO B. SAULO, Communism in the Philippines, Manila, 1969, p. 32-35. Rectify Errors…, p. 4-5.

(4). For general discussion of this line, see: AMADO GUERRERO, Philippine Society & Revolution, Oakland, 1969.

(5). CLAUDE MCKAY, A Long Way From Home, NY., 1970, p. 164-166.

(6). RICHARD O. BOYER, The Dark Ship, Boston, 1947, p. 269.

(7). PETER KWONG, Chinatown, N.Y. Labor & Politics, 1930-1950, N.Y., 1979, p. 119-128.

(8). Ibid.

(9). Ibid.

(10). Ibid.

(11). KARL YONEDA, “100 Years of Japanese Labor in the U.S.”, in Roots: An Asian American Reader, Los Angeles, 1971, p. 150-158.

(12). MICHI WEGYN, Years of Infamy, N.Y., 1976, p. 121-123.

(13). NAISON, p. 5-8. Unless otherwise noted this work is the source for the data in

(14). HARRY HAYWOOD, Black Bolshevik, Chicago, 1978, p. 121-130.

(15). Ibid.

(16). Crisis, June 1934.

(17). BEN STOLBERG, “Black Chauvinism”, Nation, May 15, 1935.

(18). Letter to the Editor for Sterling A. Brown, Ralph J. Bunche, Emmet E. Dorsay, E. Franklin Frazier, Nation, July 3, 1935.

(19). Letter to the Editor from James S. Allen, Nation, July 3, 1935.

(20). “The Question Box”, Negro Liberator, N.Y., 1940, p. 185-216.

(21). RICHARD WRIGHT, American Hunger, N.Y., 1983, p. 113.

(22). NAISON, p. 193-195.

(23). WILLIAM R. SCOTT, op. Cit.

(24). CLAUDE MCKAY, Harlem, Negro Metropolis, N.Y., 1940, p. 185-216.

(25). NAISON, p. 196-197.

(26). MCKAY, Harlem Metropolis, p. 216.

(27). MARK NAISON, “Marxism and Black Radicalism in America: The Communist Party Experience,” Radical America, May-June 1971, p. 19.