Are the problems that challenged the Chinese Revolution fifty years ago meaningful to us, halfway around the world and in an entirely different historical period? To overturn false internationalism is one key to unlocking the door before us. The time of the Comintern is not just “ancient history”, but is directly related to the molding of our own political consciousness and our own movements.

In 1960 the Southern Sit-ins marked the beginning of a great period of mass struggle, not only for the New Afrikan National Revolution but across the continental U.S. Empire as a whole. One feature of that new awakening was the twisted shape of political consciousness. Nowhere in the Black Nation in 1960 was there a New Afrikan communist organization. While there was a revolutionary nationalist political current centered then within the Nation of Islam, there was no communist organization. Neither were there communist organizations in Aztlan or the Asian-Amerikan communities. This has been unquestioningly accepted as normal. But isn’t such a state of affairs not normal but abnormal?

The Afrikan Blood Brotherhood, the first New Afrikan communist organization, was formed in 1919 at the same time as the first Vietnamese communist study groups and the Chinese Communist Party. Yet some forty years later, in a new generation of struggle, New Afrikans once again faced the necessity of building a communist center from ground zero. What happened to the work of thousands of New Afrikan communists of the 1920s and 1930s—those who fought the planters, organized unions, and took part in a militant wave of national consciousness?

The first generation of Third World communists here in the U.S. Empire were destroyed, just as the Chinese comrades would have been if they hadn’t defeated false internationalism. That is why they inherited nothing organized, why they had to learn the A-B-Cs of revolution from scratch, making so many mistakes on the way. The defeat of the previous generation was not State repression alone. What made the setback so devastatingly effective was that it was also carried out by the communist movement of the U.S. Empire.

Disarmed politically by false internationalism, Third-World communists here during the 1930s allowed themselves to be “united” into the settleristic Communist Party USA (CPUSA). This was the approved “national section” of the Communist International in the U.S. The CPUSA recruited tens of thousands of Third-World revolutionaries, but only to break them, disarm and scatter them.

We can say that, whether knowingly or not, the CPUSA served the interests of U.S. imperialism by:

1. Leading the oppressed away from armed struggle, away from joining the world revolution.

2. Convincing people that national liberation and communism were opposed to each other.

3. Using Third-World “communists” to disunite the oppressed nations, while also placing the activities of the oppressed under the constant monitoring and meddling of Euro-Amerikans. “Left” settlerism worked as a counter-revolutionary police for their Empire. And their most loyal Third-World “communists” became “unconscious traitors” to their own people.

USING THE ATTRACTION OF INTERNATIONALISM

The Communist Party USA won the allegiance of Third-World “communists” by appearing so different from the rest of settler Amerika (this was the Jim Crow 1930s). Theirs was a Party that played up the importance of anti-colonial struggles, the integration of all races and peoples, and readily confessed how it had to overcome the “white chauvinism” of even its own members. The party wrapped itself in the mantle of John Brown, formed John Brown Clubs, put out John Brown pamphlets and held meetings to praise John Brown as its model for white people. The Party not only said that it supported the right of New Afrikans to their own Nation in the Black Belt South, but in 1931 held a public showpiece trial in Harlem (the “Yokinen Trial”) to discipline a Finnish-Amerikan Party member for racism at a party social event. This was “the Party of Lenin and Stalin”, with all the authority then that such a claim carried, the official party of world communism.

Third-World revolutionaries finding this surprising Party were often won over by “the generous intoxication of fraternity”. The CPUSA seemed to be what they needed. Angelo Herndon, the Alabama worker and organizer whose defense case under the old slave insurrection law became a national issue, said: “The education I longed for in the world and expected to find in it I surprisingly began to receive in the Communist circles. To the everlasting glory of the Communist movement, may it be said that wherever it is active, it brings enlightenment and culture... My new white friends...gave me courage and inspiration to look at the radiant future... The bitterness and hatred which I formerly felt toward all white people was now transformed into love and understanding. Like a man who had gone through some terrible sickness of the soul, I mysteriously became whole again.”(1)

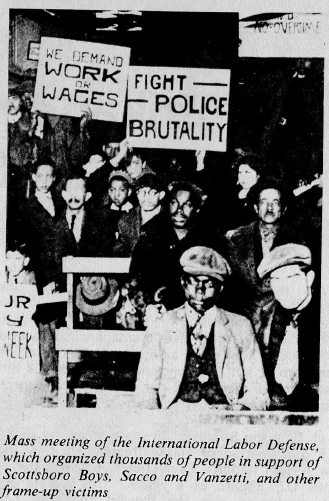

The CPUSA, unlike all previous “Left” settler parties, was very active in Third-World struggles. It became the self-proclaimed “Champion of Negro Rights”. We can see how this drew folks. Hosea Hudson, the Birmingham steel worker, has told us how he became attracted to CPUSA in 1931:

“The Communist Party was putting out leaflets, but I didn’t know nothing about the Party... I didn’t pay no attention to any leaflets til the Scottsboro case, when they took the boys off the train, and then the sharecroppers’ struggle in Camp Hill. These two was about the first thing that claimed my interest.

“The first break I know about the Scottsboro boys was in the Birmingham News on Sunday morning, had big, black headlines, saying nine nigger hobos had raped two white women on the freight train, and Attorney General Knight said he was going to ask for the death penalty... Wherever Negroes was frame-up, I would always look for someone else to say something about it. I wouldn’t say nothing because I didn’t think there was nothing I could say...until the Scottsboro case, when these people from all over the world began to talk. Then I could see some hope.

.......

“Then they had this gun battle, these Negros down there had that shoot-out at Camp Hill. The papers came out about it, and about fifteen of the leading Negros, preachers and some businessmen in it, issued a statement in the paper condemning the action of the Sharecroppers’ Union down there in Camp Hill. They put up a $1500 cash award for the capture and conviction of the guilty party who was down there ‘agitating and misleading our poor, ignorant niggers’. (Later I learnt that Matt Cole was the man who was down there, that they put up the $1500 reward for, and he was a Negro from the country just like me, couldn’t read or write.) I thought the better class ought to have been putting money up trying to help the Negroes who’s trying to help themselves. I had some wonders about it. I couldn’t understand it.

“They had filled the jails at Camp Hill full of these Negroes, and telegrams began to come in from all over, demanding they not be hung. I wanted to know what’s happening to them, what’s going to happen to them, what’s going to be done? It was the first time I ever known where Negroes had tried to stand up together in the South. I tried to keep up with it, asking people about it, and ‘what you think about it?’, getting other people’s opinions among my friends and people of my stature, all working people. I didn’t have no contact with no better class of Negroes. A whole lot of them was sympathetic to the sharecroppers. They wanted to see something done, too, to break up the persecution against the Negro people.”(2)

By supporting and then leading such breakthroughs as the armed sharecroppers movement, the CPUSA maintained its position as a false substitute to prevent an independent New Afrikan communism.

LEADING THE OPPRESSED AWAY FROM ARMED STRUGGLE

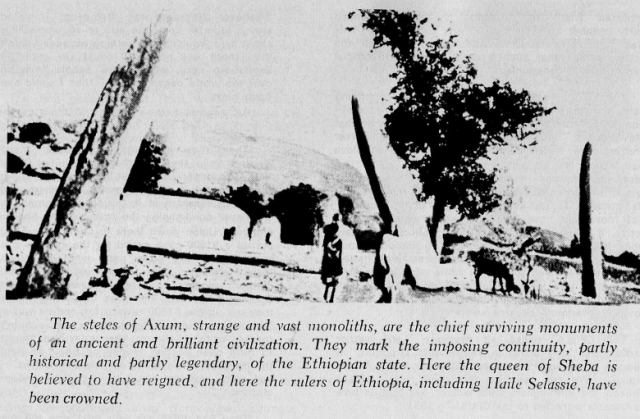

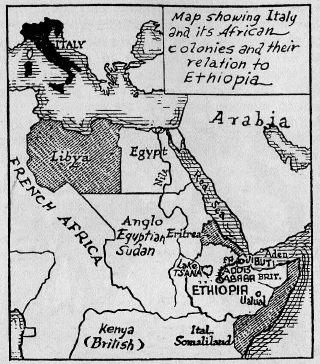

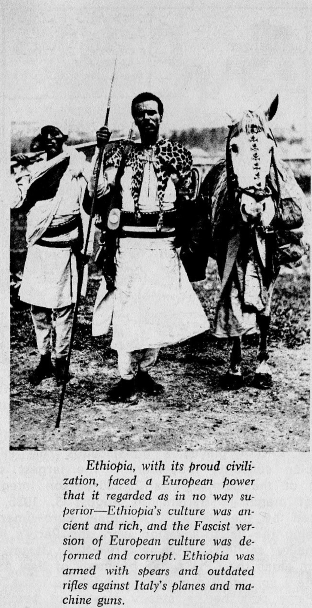

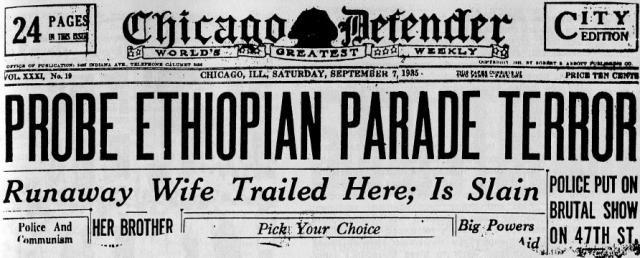

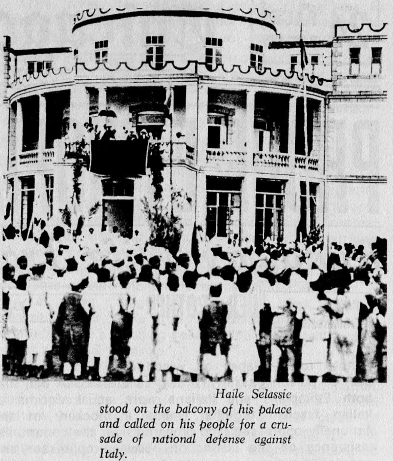

The 1935-1936 mass movement around the Italian invasion of Ethiopia was a turning point for New Afrikan rebellion in the 1930s. In October 1935 Italian imperialism sent its armies into Ethiopia, the last remaining independent Afrikan nation. Italian imperialism had sought to add Ethiopia to its other Afrikan colonies, Libya, Eritrea and Italian Somalia. Even before the fighting began it was clear that Italy was going to invade; the Ethiopian government of Emperor Haile Selassie had begun war mobilization and had sent out a call for international aid. The response and excitement were world-wide. In the continental U.S. Empire, the New Afrikan Nation was caught up in the cause of Ethiopia. It was to them in 1935 what the Vietnam war was to us in 1968. The militant solidarity movement was spearheaded by the nationalists, with everyone from the Baptist churches and the NAACP to the Garveyites and Communists joining together.

The CPUSA played a conspicuous role in this Ethiopian solidarity movement. The largest single event of the campaign, a 25,000-person integrated protest march in Harlem on August 3, 1935, was initiated by the Party. The main Euro-Amerikans opposing the Italian invasion were the Party’s Italian nationality sections in New York-New Jersey. In Harlem alone the CPUSA had hundreds of New Afrikan members spreading propaganda about the issue, while the Party published a steady stream of pamphlets, leaflets and newspaper articles denouncing the Italian fascist dictator Mussolini and the war. All this let the Party claim that it had proven its promise of “full support in this united defense”.

But here again there were two opposing lines, two diverging political directions of how to unite with Ethiopia and what internationalism meant. One line was represented by the CPUSA; the other line, most fully developed by the Chinese Communist Party, was also the line taken by the New Afrikan masses here. That line was the path of rebellion and national liberation; the other line was the path of defeatism and submission to the U.S. Empire.

The Communist Party USA defined the struggle as an “anti-fascist united front”, in which the main task facing New Afrikans was uniting with Euro-Amerikans and Europeans. Under the discipline of the Party, Black members were sent out into the community to stop angry militants from violent attacks on fascist supporters here. Likewise the Party’s Black cadres had to denounce the Volunteer Movement, the spontaneous nationalist upsurge of many thousands of New Afrikans (in particular many World War I veterans) who wanted to go fight in Ethiopia.

Party spokesman James W. Ford, while forced to admit that “The Volunteer Movement is another idea that has wide support among the Negro People”, put it down as “thoroughly impractical”. He then went further to say that the Volunteer Movement was a trick by “those who wish to talk but do nothing in reality to help Ethiopia”. The program for the movement put forward by the Party had only two points: peaceful picket lines at Italian consulates and other legal demonstrations; sending money to Ethiopia.(3) Black members and supporters of the CPUSA were disciplined to a program precisely tailored to Amerikan liberalism. Ethiopia was treated in a half-hearted way as a charity case.

Our Chinese comrades were then deep in remote regions of the countryside, struggling for survival by mastering armed struggle. For from being uninterested or half-hearted about Ethiopia, Chinese patriots took up the issue of Ethiopia in the true spirit of internationalism. Not as another Third-World charity case or “good cause” for liberals in the spare evenings. The Chinese patriots embraced the far-away Ethiopian liberation war as a positive example, a model to the Chinese nation. Internationalism to the Chinese people meant learning from Ethiopia, and united with the Afrikan people by also picking up the gun against world imperialism.

While the settleristic CPUSA looked down on Ethiopia as a backward victim who should be tossed some spare change, the Chinese people looked up to the Ethiopian masses as heroic pioneers whose example should be followed. Here we can see the difference between false internationalism and genuine internationalism.

We must focus for a moment on this: the Chinese people, from young students to Mao Zedong, had genuine respect for Ethiopia and her war. China herself was being invaded by Japanese imperialism, and the Kuomintang government refused to lead the nation to recover their independence. China, too, knew well the problems of being weak, feudalistic and unorganized. Agnes Smedley, the famous journalist, was in China during those years. She was in Peking when the Italo-Ethiopian war began:

“The Chinese people writhed under the humiliation of defeat and impotence. Students who had demonstrated against the Japanese and demanded war were beaten in the streets and imprisoned...

“When, later, Italy copied Japanese technique and occupied Abyssinia (Ethiopia was also known as Abyssinia then) the resistance of the Abyssinians lit new fires of patriotism in the Chinese people. If little Abyssinia could fight a powerful invader so courageously, so could China, argued all Chinese patriots... Each weekend men and women students gathered by hundreds in the Western Hills on what they called ‘picnics’. I heard anti-Chinese foreigners accuse them of sexual debauchery. What they were really doing was practicing mountain-climbing and guerrilla warfare. Sticks were their weapons, and stones were their hand-grenades.”(4)

Should it be a surprise that a small Afrikan nation fifty years ago helped the Chinese people rise to their feet?

On December 23, 1935, Gen. Chu Teh of the Red Army issued an open letter to the officers of an opposing Kuomintang Army from Szechwan province, challenging them to follow the Ethiopian people:

“For two months now the Abyssinians have been fighting for the independence of their country. Though Abyssinia has a population of only 10 million and a territory of only 300,000 square miles, its people are still fighting an imperialist power many times their numerical and military strength... You, Szechuan officers, have many millions of soldiers, and you have good modern weapons. Why can’t you even dream of following the example of little Abyssinia whose dark soldiers are fighting gloriously for their independence? Why should not brave and gallant men in our country also step out to fight for national survival?”(5)

Compare these fighting words with the words of James W. Ford, the CPUSA’s main spokesman on Ethiopia, in opposing armed struggle: “It would seem, therefore, that the more practical thing to do in this connection would be to send every penny we could raise to help the people of Ethiopia... We can flood the Italian consulates and Embassies with telegrams and resolutions of protests.”(6) There is, of course, nothing abstractly wrong with these tactics as such. But to insist that an oppressed people who want to rise up should limit themselves to liberal protests is “to preach submission to the yoke”.

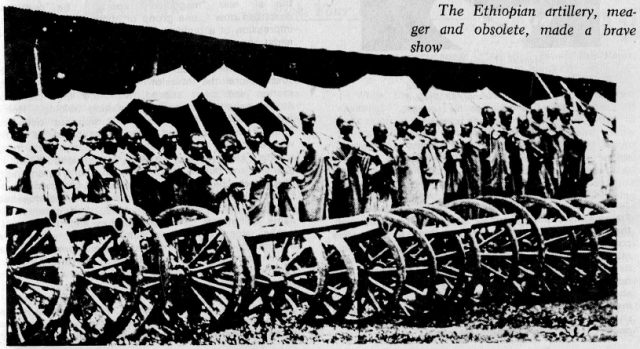

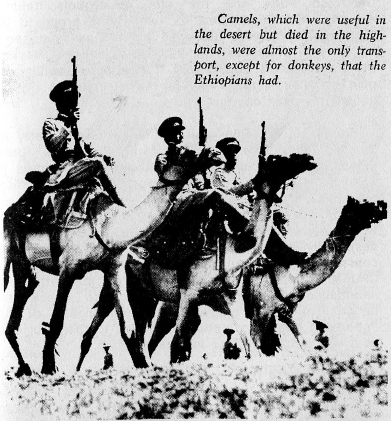

The Italian invasion was a triumph due less to imperialist strength than to poor military strategy by the Ethiopians. 800,000 Italian troops armed with tanks and air squadrons, using poison gas, pushed aside the brave but ill-led Afrikan soldiers who tried to stop them in direct positional warfare. On June 2, 1936 Emperor Haile Selassie and his leading officials evacuated Addis Ababa, the capital, and fled to exile. The war was not over, however.

Italian imperialism, which had indeed imposed a brutal fascist dictatorship on the Italian proletariat, proceeded to go far, far beyond this in Ethiopia. There again the difference between political repression and national genocide was demonstrated. Mussolini’s son Vittorio was a fighter pilot in the invasion, and he regaled European reporters with his accounts of how hunting Afrikans from the safety of the air was “magnificent sport”. He poetically described how “...one group of horsemen gave me the impression of a budding rose as the bomb fell in their midst and blew them up.”(7)

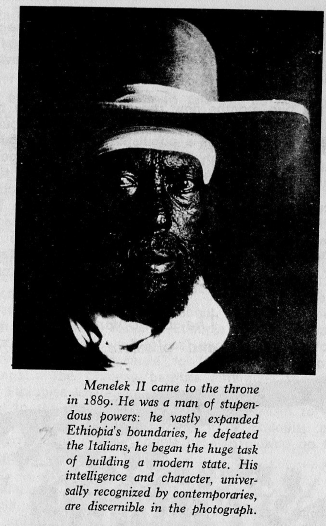

The invaders tried to destroy Ethiopia as a nation. Just before the invasion the first modern school system had been started, with the first class of Afrikan school teachers just finishing training. Rome ordered all of them killed. Throughout occupied Ethiopia every educated Afrikan that could be found was executed. The Italian troops, bored with firing squads, killed many Afrikans by soaking them in gasoline and burning them alive (in public demonstrations, of course). Because Italy feared even the memory of Ethiopian Emperor Menelik, whose armies had smashed the first Italian invasion of 1896, they ordered his name obliterated. Melenik’s statues and the imperial tombs (along with many cultural monuments) were dynamited. When hidden arms caches were found in a search of Ethiopia’s most famous monastery, Italian Viceroy Graziani had 400 Ethiopian monks and deacons slaughtered.(8)

Unable to control seething Ethiopia, the Italian occupation conducted daily arrests and executions of suspected patriots. Mussolini personally ordered that remote rural villages be wiped out with “maximum use” of poison gas.(9) To say, as the CPUSA did, that both Ethiopians and Italians were equal victims of Italian fascism together, made a mockery of the nationally oppressed (and smeared over the communist insistence on the distinction between oppressor and oppressed nations).

ETHIOPIA AND NEW AFRIKA – SAME STRUGGLE

When the nationalists saw a special relationship to Ethiopia they were, of course, quite correct. Everyone knew that U.S. finance capital supported the Mussolini regime. Moreover, the fascist Mussolini regime and the invasion of Ethiopia were supported by many Euro-Amerikans of all classes. There was a certain love affair between Fascist Italy and White Amerika. They had a lot in common; two oppressor nations ruling large Afrikan colonial populations. That is why the New York correspondent for the Corriere Delta Sera, Italy’s most respected newspaper, wisely reassured the Italian public after Emperor Selassie fled that the Euro-Amerikan people would not really oppose the occupation: “America knows the Negro well, and understands how to treat him.”(10)

While the Roosevelt Administration and the two capitalist parties issued token statements of opposition to the war, the U.S. Empire was close to the Italian Empire. The Italian government had openly backed the election of then New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, with funds as well as words. Pleased that President Roosevelt’s early New Deal cabinet included outspoken followers of Mussolini’s theories, Mussolini himself sent off a message praising “the intensive cult of dictatorship to which President Roosevelt is dedicating himself.”(11) This love-feast was even seen in popular culture—in 1934, as the invasion neared, Euro-Amerikans made a big hit of Cole Porter’s new song, “You’re the tops—You’re Mus-so-Li-in.”(12)

The U.S. bourgeoisie, not needing to observe the hypocritical poses of capitalist statesmen, was out-front in backing the conquest of Ethiopia. Business Week’s editorial for February 23, 1935 was titled “Abyssinia for the Italians”. It said that since Italy had fewer colonies than the other Powers, they deserved sympathy in “exploiting” the only Afrikan nation still available. After the conquest, Myron C. Taylor, Chairman of the U.S. Steel Corporation, held a lavish banquet at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel to honor the new Italian Ambassador. Taylor toasted the conquest, praising Dictator Mussolini for “disciplining” Ethiopia.(13)

While most Euro-Amerikans were primarily indifferent to events in Afrika, the Italian-Amerikan community was solidly behind Mussolini. The invasion aroused “Italian pride”, making the mostly poor Italian immigrants happy that “their” homeland was conquering Third-World nations just like the other European Powers. The anti-Afrikan, pro-imperialist sentiment of the Italian-Amerikan community was spontaneously strong, although also heavily reinforced—at neighborhood movie theaters the newsreels showed Italian Bishops using holy water to bless Mussolini’s tanks going off to battle. The Vatican itself had said that Italian colonization was bringing “civilization” to Afrikans.(14)

One history of U.S.-Italian relations recalls the hysterical fever of national chauvinism that was manifested by the Italian-Amerikan masses in 1935:

“For Italian-Amerikans the Ethiopian War was a sustained catharsis. Tens of thousands of them turned out for rallies in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and elsewhere. Here women contributed their gold wedding rings, receiving steel rings from Mussolini which were blessed by a parish priest. At a Brooklyn rally the Italian Red Cross passed trays to collect gold watches, cigarette lighters, crucifixes, and other metallic mementos needed to finance the war... At another Madison Square Garden rally, Generoso Pope told an audience of 20,000 that he was to send a check for $100,000 to Rome, and his paper, Il Progresso, confidently announced that ‘5,000,000 Italian-Amerikans who live in the United States are ready to immolate themselves on the altar of the great motherland.”(15)

Pope’s Il Progresso was the most popular Italian-language newspaper in the U.S. Its special campaign to help finance the invasion raised $1,000,000, with Italian-Amerikan small businesses contributing to support the invasion. Some of this money came directly from Harlem, extracted from New Afrikans themselves. At that time the busy stores, bars and restaurants in Harlem were owned and managed by settlers, including many Italian-Amerikans. Each Italian store had a photograph of Mussolini prominently displayed. James R. Lawson relates: “No Black man could, in good conscience, go into most Italian bars in Harlem. Mussolini’s picture hung over almost every Italian cash register up there.”(16) Claude McKay wrote back then that: “The Italians control over seventy-five percent of the saloons and cabarets in Harlem... Their patronage was 95 percent Negro...”(17)

The anti-Afrikan sentiment in the Italian-Amerikan community was so overwhelming that the Communist Party USA decided to compromise with it. While the Party’s Black cadres were sent out to convince their community about the need to unite with Italian-Amerikans, the Party’s work in that latter community tacitly went along with the pro-Imperialist majority. That is, the Party found ways to soft-peddle or back off from the issue.

A sore problem was Congressman Vito Marcantonio, the radical Italian-Amerikan politician from upper Manhatten. He was the Party’s closest ally in bourgeois politics during the ‘30s and ‘40s; the Party managed his campaign, supplied his funds, and lent him hundreds of campaign workers. In return, Marcantonio verbally lambasted capitalism and colonialism on the floor of Congress. He was the main Washington voice attacking U.S. colonial rule over Puerto Rico. But on this issue he was in trouble. While most Italian-Amerikans were indifferent to Puerto Rico, any strong supporter of Ethiopian independence would lose badly in the Italian wards on election day.

Marcantonio’s solution was to still criticize Mussolini, but to find radical-sounding positions from which to come out against Ethiopia. So when New Afrikans here fought back against pro-fascist Italian-Amerikan gangs, Marcantonio denounced them for “race riots”. When he had to consider the League of Nation’s sanctions banning sales of arms and war supplies to Italy, Marcantonio opposed it as supposedly not anti-imperialism enough, as just a plot favoring British interests against Italian interests.(18)

During a debate on the war in the House of Representatives, Texas liberal Maury Maverick stated: “We may as well agree that certain special groups have come into the picture. I refer to the letters of certain leaders of Italo-American groups...saying they are entitled to special consideration for Italy.”

Marcantonio jumped to answer: “Mr. Speaker, my good friend, the gentleman from Texas, has referred to the so-called Italian-Americans requesting special consideration in the matter of neutrality legislation. I simply want to inform my colleagues of the House that these so-called Italian-Americans are Americans of Italian extraction, and that the Americans of Italian extraction are not requesting special consideration. They are interested only in the welfare of America... It is their desire to keep our nation out of war. They want peace. They are opposed to any scheme which would make our nation the tool of either the international racketeerism of the League of Nations or the imperialistic interests of any foreign nation.”(19)

In Congressman Marcantonio’s “Left” rhetoric, not taking sides against Italy was labeled a “peace” measure. He even stretched things so far that Generoso Pope and the other bourgeois Italian-Amerikan community leaders (who were proud to be pro-Imperialist) were defended by him as supposedly being anti-imperialist. Still, the CPUSA backed Congressman Marcantonio up. They were unwilling to give up their biggest ally in the mainstream of the Italian-Amerikan community.

When Marcantonio praised the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico, few Italians cared and his pro-independence posture won him thousands of votes in Spanish Harlem. But to support Afrikan liberation would have driven him out of Congress. His Italian neighbors would have turned on him as a traitor to white supremacy. The Communist Party USA was deservedly close to Marcantonio, both steering a course of cynical opportunism together. So when the CPUSA manipulated its Black cadres into attacking nationalism, that Party only meant to attack the nationalism of the oppressed; the nationalism of the imperialist oppressor nations was fine to them so long as it was draped in false internationalism.

For all these reasons the work of CPUSA members in the Ethiopian support movement went on the opposite path from that taken by the New Afrikan masses. The program of the masses leapt right over sending “every penny” to Ethiopia or picketing a downtown office building. They weren’t opposed to these things, but first and foremost they wanted to fight. Afrika was going to war for national survival, and the grassroots wanted to do their part in the War. In the Summer of 1935 a spontaneous upsurge rocked New Afrika, as thousands reached to pick up the gun. Many World War 1 veterans itched to at last use their skills fighting for their own cause. The Baltimore Afro-American reported that within a week the nationalist drive to sign up fighters for Ethiopia had produced almost a thousand volunteers in Harlem, 8,000 in Chicago, 5,000 in Detroit, 2,000 in Kansas City, and 1,500 in Philadelphia.(20) Is it so difficult to read the meaning of this movement? Even the unfriendly James W. Ford of the CPUSA had to concede that the Volunteer Movement had “wide support” for its “heroic sentiments”.

Just like the Chinese people, the New Afrikan colony was fed up with “the humiliation of defeat and impotence”. The attitude on the streets was, “Let the white liberals send telegrams to the Italian Embassy, we’re going to fight for the Race.” And that, of course, was the other aspect of the mass upsurge. However few or many made it to Ethiopia, the battleground for New Afrikans could only be right here in the U.S. Empire. Just like the Chinese people, the New Afrikan masses correctly read the lesson of the Ethiopian War as fighting for their own national liberation. But there was no independent New Afrikan communist vanguard to organize this raw sentiment into a spearhead.

The day after the Italian invasion spontaneous mass fighting with fists, rocks and baseball bats, broke out between angry New Afrikans and pro-imperialist Italian-Amerikans in both Harlem and Brooklyn. Over a thousand police were needed to stop the violence. In Harlem, Italian stores and Italian street-vendors—who were in general pro-Mussolini—came under physical attack by nationalist crowds. At evening, coming home from “the slave”, hundreds and sometimes thousands in Harlem would stop to listen to the nationalist street-corner orators. Soon crowds fighting with the police, throwing rocks at police cars, became a part of community life. Pointing out the contradiction of New Afrikans giving money to the Italian war effort by having to buy from Italian merchants, nationalists called for New Afrikans to take over the economic life of their community and solve their own survival problems as well.

On the political level, New Afrikans overwhelmingly wanted a mass united front to link their Nation up with the war for Ethiopia. While the degree of political consciousness in 1935 should not be overstated, an oppressed people who began to rise up, who wanted a national united front against imperialism, had chosen the path of liberation. That they had to do so without an independent New Afrikan communism was a contradiction within the National movement.

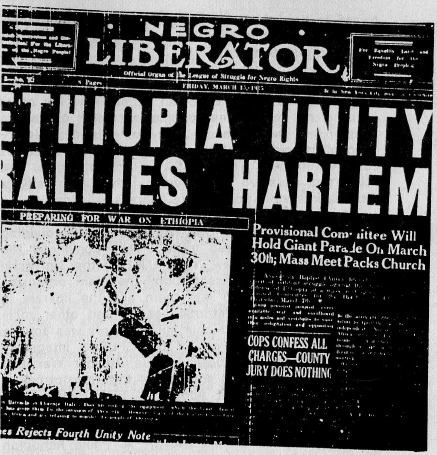

DIVIDING THE NATION AGAINST ITSELF

While always shouting about unity, false internationalism was applied to divide New Afrika against itself. To begin with, the CPUSA’s Black cadres split the Ethiopian solidarity movement so that it could be wiped out. Euro-Amerikan revisionism always portrayed New Afrikan nationalism as “narrow”, as promoting “racial exclusiveness”. But in 1935 the various nationalist organizations led in building a national united front around anti-imperialism together with the Communist Party USA and the integrationist liberals such as the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. That united front, which was at first named the Provisional Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia, held its first rally on March 7, 1935. On a rainy night over 3,000 people jammed Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church. Wall banners read “Africa for the Africans”, while Ethiopian flags of green, gold, and red were waved by the crowd. Speaker after speaker, including the prominent Harlem educator Dr. Willis Huggins, saluted the national unity achieved.(21)

The nationalist leaders displayed an internationalist orientation to the struggle and were in no way sectarian or “racialist”. J.A. Rodgers, who had returned from a fact-finding mission to Italy, told the crowd: “The Italian people are not unfriendly to Negroes, as experiences during my travels prove. This threatened attack on Abyssinia is a result of other forces operating within Italy.” Rodgers pointed out how the first Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1896 had been opposed by Italian workers with a general strike. After CPUSA spokesman James W. Ford pledged their support to the united front, the largely nationalist audience cheered. Then Arthur Reid of the African Patriotic League, one of the most militant of the nationalist organizations, rose to point out the importance of bringing communists into the united front:

“There was some fear that the communists would not come through with flying colors in this meeting, but the speech of Mr. Ford has stilled that fear. The Communists have proven that all of us can work together. They have come through” Reid said that this anti-imperialist unity was fulfilling the dream of Marcus Garvey: “We must unite, and after we unite we must fight.”(22)

The CPUSA had also portrayed itself as a force for unity. James W. Ford had told the Harlem rally: “If we would stop fighting among ourselves... long enough to unify our forces against our enemy—we would advance. Unless we do this we perish. But I don’t believe we are going to perish. We are going to stick together.”(23) The very next day the CPUSA began its campaign to split the young Ethiopian support movement. They demanded that the movement become an integrated one, and that the committee surrender its specific national character. Ford promised the committee thousands of Euro-Amerikan supporters, lots of “respectable” liberal endorsements, and thousands of dollars—if the “extreme nationalists” were kicked out. So much for unity.

The CPUSA had redefined the Ethiopian war as a joint anti-fascist struggle of Italian workers and Ethiopian patriots, which should be supported in Amerika by a joint movement of “Negro and white”. CPUSA spokesman Ford wrote:

“Certain Negro leaders in the united front refused to vote on the participation of the Italian workers in the united front, stating that they were willing to work with Negro radicals and Communists but would have nothing to do with white radicals. By the small margin of one vote, the count being 8 to 7, their participation for the time being was overridden.

“In view of the activities among the Italian workers in Italy under the leadership of the Communist Party and the willingness of Italian workers in the U.S.A. to work together with Negro people for the defense of Ethiopia, it is now clear that the policies of the extreme nationalists among the Negroes work against the interests of the defense of Ethiopia. These petty-bourgeois nationalist tendencies must be overcome if the real interests of the exploited Negro masses and the Italian workers are to be defended against fascism and war.

“A great task lies before us. Let us not permit our forces to be divided. Let us unitedly give the Ethiopian people and the Italian toilers that help which we can and must give.”(24)

In this false internationalist view, the closest allies of co-victims of the Ethiopian people were not other Afrikans, not the Chinese people, not other oppressed people—but the Italians. Likewise, this false internationalism pictured New Afrikans’ closest allies as Euro-Amerikans. The CPUSA’s Black members and supporters were led to believe that the closest ally of each oppressed nation was its oppressor nation.

By July 1935 the CPUSA had succeeded in dividing the New Afrikan united front. They convinced the leadership of the New York U.N.I.A. (the Universal Negro Improvement Association—the main organization of Garveyism) to join them and the liberals in ousting the African Patriotic League and other militant activists. Then Ethiopia support work was actually merged into the work of the CPUSA’s integrated front-group, the American League Against War and Fascism. The outward success of this transformation was seen in the giant August 3, 1935 Harlem joint march against Italian aggression. With the CPUSA in charge, the march had no trouble in getting support from Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, A. Philip Randolph of the A.F.L., and many settler churches and unions. The result was a dazzling 25,000-person integrated march through Harlem: Euro-Amerikan college students and Garveyite security guards in uniform with the white-clad religious cultists of Father Divine and red arm-banded Euro-Amerikan garment workers. Thousands of Euro-Amerikan radicals took part in the grand parade.

Many New Afrikan activists were blinded by this outward unity and quantitative success. J.A. Rodgers said: “When white workers march in such numbers in such cordiality through a Negro neighborhood, it is something for Negroes to think very deeply about.” By the Fall the movement had gone “big-time” and had essentially moved its base out of the New Afrikan community. The grass-roots were being abandoned. The next major event was at Madison Square Garden, where 9,000 people (mostly Euro-Amerikan) applauded Captain A.L. King of the U.N.I.A. when he said: “This is a fight of the masses against the classes. We Black people will join you liberal whites all over the world not only to protect the rights of Negroes but in the interests of all mankind.” Parades and glittering events had supplanted hard struggle at the grassroots.(25)

By September 1935 the CPUSA newspaper, Negro Liberator, was writing: “We call upon the already aroused Negro people in America to join hands with the Italian people and the white toilers... The Italian workers are fighting Mussolini right in his own backyard. FOLLOW THEIR LEAD, American workers! DOWN WITH THE ‘RACE RIOT’ INSTIGATORS!”(26) In other words, New Afrikans were being told to oppose uprisings at home and instead “follow” Italians. Supposed solidarity with Afrika was turned into its opposite.

There was no active struggle—armed or otherwise—by Italian workers against the brutal occupation of Afrika. Because of the success of Italian fascism’s repression there was no longer an active workers’ opposition inside Italy by 1936. The CPUSA’s newspapers, including the Negro Liberator, kept reporting various Italian anti-war strikes, demonstrations, etc. But these supposed underground reports were nothing but fiction. The Comintern and the leadership of the Italian Communist Party, isolated in exile in Paris, had put out these propaganda inventions to cover up for their shortcomings.

While the Italian Communist Party published statements expressing anti-imperialist solidarity with the Ethiopian people, these statements had no reality in deeds. If anything, the reverse politics were being practiced. The Italian Communist Party leaders had been reduced to trying to get in with the fascists. They were actually begging for a united front with fascism! Nothing of this was revealed here to the New Afrikan community, of course.

After months of discussion, the Comintern and the Central Committee of the Italian Communist Party in exile had issued a major call for Italian oppressor nation reconciliation in August 1936. Issued on the occasion of Italian dictator Mussolini’s official proclamation of victory over Ethiopia, the Italian communist call was titled “Reconciliation of the Italian People for the Salvation of Italy”. In it Mussolini and his colonial crimes in Afrika were tacitly accepted: the line was advanced that the Italian workers should unite behind the fascist state in order to rid it of the “fistful of big capitalist parasites”, “the sharks”, who alone had kept fascism from bringing prosperity to all Italy:

“To the Workers and Peasants

“To the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Militiamen

“To the ex-combatants and volunteers of the Abyssinian War...

“To the entire Italian People!

“Italians!

“The announcement of the end of the African war was greeted by you with joy because in your heart hope has been kindled that you will finally see an improvement in your difficult living conditions.

“It was repeated to us that the sacrifices of the war were necessary to insure the well-being of the Italian people, to guarantee bread and jobs for all our workers, to realize—as Mussolini said—‘that highest social justice which from time immemorial is the longing of the multitudes in their bitter daily struggle for the most basic necessities of life’, to give land to our peasants, to create the conditions of peace.

“Several months have gone by since the end of the African war, and none of the promises which were made to us have been kept... only the fraternal union of the Italian people, achieved by the reconciliation of fascists and non-fascists, will be able to smash the power of the sharks in our country, and force them to keep the unfulfilled promises made to the people for many years...

“Italian people!

“Fascists of the old guard!

“Young fascists!

“We communists take for our own the fascist program of 1919, which is a program of peace, freedom, and the defense of the workers. We say to you: Let us unite and struggle together to make this fascist program come true...

“Let us grasp hands, sons of the Italian nation! Let us grasp hands, fascists and communists, catholics and socialists, men of all opinions. Let us grasp hands and march side by side to win the right to be citizens of the civilized country which ours is. We suffer the same hurts. We have the same ambition: that of making Italy strong, free and happy...”(27)

Of course the fascists, already firmly in power, scorned this plea for a united front. While the Comintern had approved that opportunistic move, with its failure Moscow center washed its hands of the Italian Communist Party leaders. After six months the united front with fascism line was reversed. The Comintern started investigating the Italian communist leaders for Trotskyism and possible infiltration by fascist agents. In 1938 the entire Italian Central Committee was dissolved as unreliable.(28) The European leadership that New Afrikan people here in the U.S. Empire were supposed to “follow” were at best unconscious traitors, both to their own people and to genuine internationalism.

The CPUSA’s divide and conquer tactics had resulted in a large rise in its power within the Nation. For example, it became strong enough to stage a well-publicized slander campaign against Dr. Willis N. Huggins, the assistant principal of Harlem Evening High School. Huggins was the most prominent nationalist educator in the Ethiopian support movement. In the Summer of 1935 he had been sent by the Provisional Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia to Geneva, to use the League of Nations as a world forum for rallying Afrikan support for Ethiopia. With the aid of Amy Jacques Garvey and C.L.R. James, Huggins met with the Ethiopian Ambassador to London. Their meeting resulted in a public statement of recognition by the Ethiopian Government for New Afrikan support activities. Dr. Huggins was also the founder of Friends of Ethiopia, which with 106 local branches was the most wide-spread New Afrikan solidarity organization.

But when Huggins protested against the CPUSA’s takeover of the united front, they staged a campaign villifying him as a “fascist”, and as a supposed enemy of Ethiopia. The CPUSA publicly demanded that the Board of Education fire him, and even started a mass letter-writing campaign to Huggins’ employers.(29) Strange tactics for those who said that New Afrikans must unite or “perish”.

When the CPUSA split the Ethiopian support movement, they also dismantled its foundation in the masses and moved the campaign downtown. The struggle for Ethiopia in Harlem intersected mass life around the questions of who ran the community’s businesses and how could New Afrikans solve their economic problems? The nationalists had one program for these questions. For them the struggle of Ethiopia and the struggle of New Afrikans were sides of the same struggle.

In May 1935 the Afrikan Patriotic League began a boycott of Italian Icemen, while calling for the total ouster of Italian business from the community.*

* Before World War II there were no mechanical refrigerators. Wooden ice-boxes kept food cool, but required a new block of ice every few days. So every house was serviced by one or another ice-man (who had regular delivery routes like fuel-oil trucks or milk-men). As a low-capital, high-labor small business it was dominated by European immigrants. In Harlem, Italians owned most routes.

In particular they called on New Afrikans to stop patronizing the Italian bars. This was linked to a program of encouraging New Afrikan small business and retailing, while also doing mass struggle to enlarge employment in the community.

The nationalist call was very popular on the streets, since the contradiction of spending your meager dollars every day to financially support the conquest of Ethiopia was galling. Particularly since these same Italian-Amerikan businesses that contributed to Mussolini’s military also refused to give jobs to New Afrikans and then rubbed it in by proudly displaying pictures of their champion, the Italian Dictator. Small wonder that many people wanted to sweep them away. At the large Abyssinian Baptist Church rally on March 7, 1935, a woman had stood up at the end of the meeting to ask for a boycott of Italian business in Harlem. A nationalist speaker suggested that such a boycott would be premature: “We will have to wait and see how these people act and meet them halfway.” So the militancy of the masses had been doubly sharpened by the fact that these oppressor nation petty-bourgeois had been given a chance to change their ways.(30)

The CPUSA assembled a counter-attack to protect their integrationist schemes. Under their leadership the Provisional Committee denounced the nationalist campaign, proposing instead a mass boycott of goods imported from Italy. They publicized supposed blows against Italian aggression when they got many Euro-Amerikan businesses in Harlem to sign pledges not to sell imported Italian products. All such merchants were certified by the CPUSA as “anti-fascist”. So the ice vendors pledged to import no ice from Italy, the bars promised to import no whiskey, beer or gin from Italy, and so on. This campaign was totally phony, since New Afrikans bought little in the way of imported Italian food, clothes or other consumer products. It was also besides the point.

The CPUSA and the integrationist liberals kept insisting that any attacks on Italian-Amerikan business only divided the ranks of Ethiopia’s supporters. Not only was that a complete lie, but so was their claim that Italian workers were anti-fascist. James W. Ford pointed out that: “the Italian Workers Club of New York by telegram and through a delegate offered to come into the united front with the Provisional League for the Defense of Ethiopia.” That sounded nice, but the Italian-Amerikan anti-fascists could only muster a few hundred people, a small radical exile community, for their events, while the Italian-Amerikan pro-fascists held regular community rallies of thousands. Even in the giant 25,000 person Harlem march the Italian-Amerikan radicals could only bring a few hundred workers. Once again, the visible “friendship” of a few settler radicals was advanced as the reason for embracing a hostile nation of oppressors.

On the other hand, while Italian businesses in the ghetto were natural targets, political campaigns centering around control of small retail trade were not the center of anti-colonial struggle. The nationalists spoke from the desires of the masses, but they themselves were unable to unite, unable to effectively mobilize the sentiment they represented, and unable to give scientific leadership to the whole Nation. While the nationalists expressed the community’s anti-imperialist anger, it was the CPUSA and the Black liberal establishment that won the mainstream leadership.

In China during this same time patriotic students organized similar boycotts of Japanese products. There were similar violent reprisals against retail business that served the Japanese invaders. But that patriotic activity was just one strand in China’s larger tapestry, along with cultural struggles, women’s liberation, class awareness, and the great front of armed resistance, all guided by communism. The contrast is significant.

Both the CPUSA and its Black petty-bourgeois allies shared a common attraction towards Euro-Amerikan society. This was masked by lofty speeches, full of not only false internationalism but claims on nationalism as well. The Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. attacked the militant nationalists while hiding behind the name of Marcus Garvey: “The cause of Ethiopia is not a lost cause, but it is lost if we look at it from a nationalist viewpoint... The militancy of Garveyism must be retained, the solidification of Garveyism must be carried on, but we must move within a greater program... the union of all races against the common enemy of fascism.”(31) These oily words reveal how strong the nationalist sentiment persisted at the grassroots, how even opponents had to pretend to honor it.

PROMOTING DEFEATISM AND BETRAYAL

This was not a question of which leaders would march at the head of the mass movement. Deprived of its national united front, deprived of its roots in the daily struggles of the masses, robbed of its fighting character, confused by a process of embracing the oppressors, the nationalist mass movement broke up. Particularly after the Italian army took Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, in June 1936, the mood of defeatism in the community became dominant. The question of which line to follow proved to be an immediate question of life or death for the movement.

Interestingly enough, the same two-line struggle was going on in China. There, too, the defeatism around Ethiopia was not abstract but was rooted in defeatism around their own revolution. So much so that Mao had to confront this directly in his Yenan lectures “On Protracted War”. He noted: “Before the War of Resistance, there was a great deal of talk about national subjugation. Some said, ‘China is inferior in arms and is bound to lose in a war.’ Other said, ‘If China offers armed resistance, she is sure to become another Abyssinia.’ Since the beginning of the war, open talk of national subjugation has disappeared, but secret talk, and quite a lot of it too, still continues.”(32)

The CPUSA and the Black petty-bourgeoisie in general were pushing a policy of defeatism. Their view was that is was no use for New Afrikans to raise their arms to fight in Afrika, to fight anywhere. All hopeless, all doomed, according to that slavish line. Only by relying on Europeans and Euro-Amerikans could they receive a few crumbs. So CPUSA spokesman James W. Ford attacked the spontaneous upsurge of armed volunteers for Afrika as “thoroughly impractical”. Even in his attack, Ford had to concede that going to war against imperialism represented a personal decision of tens of thousands:

“The outfitting and transportation of 50,000 American Negro soldiers to Ethiopia, besides requiring a tremendous financial outlay, would mean 50,000 more mouths to be fed by the Ethiopian people. That is, provided they could ever reach Ethiopia. Ethiopia, it must never be forgotten, is surrounded by the colonies and war bases of other imperialist powers... The expedition would be costly, to say the least: would never reach its destination, and would divert energy and funds from assisting the Ethiopian people in a more real and powerful way.”(33)

Could anyone write a speech that was more dragged down with whining, with defeatism and contempt for their own people? We can see why James W. Ford and other such Black leaders were at best “unconscious traitors”. Such a problem — 50,000 volunteer New Afrikan fighters but with no war to fight in. How about their own war? If 50,000 New Afrikan fighters couldn’t reach Ethiopia, what could stop them from fighting on the South Side, in Harlem, Alabama and Mississippi? How can communists say that something is bad when 50,000 oppressed men and women reach for arms and ask for leadership against imperialism? And at that very moment the armed sharecroppers movement in Alabama, which involved thousands of New Afrikans, was fighting on in isolation. This is why we say that within the 1930s anti-imperialist movements there were two lines on how to unite with Afrika and what anti-imperialism meant—one line led to national liberation and armed struggle, the other line led to defeatism and submission to Empire.

After the fall of Addis Ababa the CPUSA did nothing to stop mass discouragement about Ethiopia’s prospects. Quickly they moved to phase out Ethiopia as an issue. Only J.A. Rodgers, John Robinson, and nationalists around the Ethiopian World Federation still kept pointing out that the war was not over, that the Ethiopian people were still fighting.

Mao himself emphasized at the time: “Why was Abyssinia vanquished?... Most important of all, there were mistakes in the direction of her war against Italy. Therefore Abyssinia was subjugated. But there is still quite extensive guerrilla warfare in Abyssinia, which, if persisted in, will enable the Abyssinians to recover their country when the world situation changes.”(34) Mao’s confidence in the Afrikan peoples’ struggle against imperialism was quite correct. It was the calm judgment, unshaken by momentary setbacks, of a Chinese revolution that had already found its own “center of gravity” in armed struggle.

In fact the imperialist media painted the Italian position as much more favorable than it was. Due to the dispersed nature of rural Ethiopian society, the mass war mobilization was just beginning when the Italian army struck. The Ethiopian mobilization reached its peak during the Italian occupation, just when the U.S. press was saying the war was over. Continued resistance and counter-insurgency were savage. When the Italian Viceroy Rodolfo Graziani was almost assassinated in February 1937, the Italians killed 30,000 Afrikans in random reprisals. One leading historian commented:

“Never was Ethiopia under firm control. A vast amount of propaganda about the glories of empire cannot conceal the fact that the Italian army remained encamped there amid a hostile population which was just biding its time to rebel.”(35)

In June 1936, U.S. Minister in Addis Ababa, Cornelius Van H. Engert, wrote Washington that the occupation was weak. Engert said that the imperialist forces didn’t even claim to occupy more than 40% of Ethiopia. The vast rural areas west of Addis Ababa were totally commanded by Afrikan guerrillas. The Italian army had been hit so hard in ambushes, according to the U.S. Minister, that they were afraid to move more than five miles beyond the capital without a force of at least one thousand troops.(36)

So the defeatism about Ethiopia (which was really based on defeatism about all national liberation) was incorrect. In fact, although the Italian occupation would have been swept out by the Ethiopian people alone, the changes in the world situation led to the defeat of Italian imperialism within five brief years.

While the duty of communists was to help the masses put down defeatism, under the leadership of the CPUSA they actually did the reverse. The CPUSA told people that is was useless to continue supporting Ethiopia. They did this by saying that the only solution to Ethiopia’s subjugation was to defeat fascism back in Europe. In other words, once again Europe was raised as the supposed salvation of the colonial peoples.

In the Spring of 1937 the Spanish Civil War began. The young democratic Spanish Republic was threatened by a fascist revolt within the Spanish Army, aided by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. All over the world communists raised material support for Spanish anti-fascists. The CPUSA began openly recruiting thousands of volunteers to fill out the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, which would be the all-U.S. Empire unit fighting in the Spanish Republican Army. New Afrikans were told to forget Ethiopia; that only by overcoming fascism in Spain would the Italian occupation be lifted. This lie carried contempt and defeatism about the liberation war of the Ethiopian people, a war that at that moment was still rising. The CPUSA’s Black cadres were ordered to spread the new slogan: “Ethiopia’s fate is at stake on the battlefields of Spain.”(37)

This slogan was wrong in many ways: First, it was factually untrue in its form—that is, while Ethiopia was never defeated and regained its independence in five years, Spain was easily conquered by fascism. Further, Spanish fascism remained in power for thirty years, Most importantly, the Ethiopian people had to depend primarily on themselves alone for victory: not on Spain, not on China, not on Russia, or any other nation. The fate of Ethiopia never rested on any events in Spain.

Thousands of Blacks were mobilized to work for the Spanish Republic—as opposed to supporting Afrikan liberation. Medical supplies and funds collected for Ethiopia by CPUSA-controlled committees were instead sent to Spain. (No one in Afrika or Alabama apparently needed liberation aid.) Just the year before the CPUSA was saying how “impractical” it was to send armed volunteers to Ethiopia. Now the CPUSA was telling New Afrikans that it was their internationalist duty to go fight in Spain. Incidentally, Republican Spain no less than Ethiopia was surrounded by imperialism. New Afrikan fighters in Spain had to be smuggled through France, covering the last leg to the border by a march through the mountains. One hundred New Afrikans served with the Republicans in Spain. Two died in combat, giving their lives to the world revolution. That they fell in battle was not tragic; what was tragic was that their courage and internationalist dedication were cynically manipulated and misused by the CPUSA. Their picking up the gun in Europe was used to divert New Afrikans from their own national liberation, away from genuine internationalism with Afrika.

So in 1935-1937 the settleristic Communist Party USA, together with petty-bourgeois Black elements, manipulated Black CPUSA members and supporters to destroy the nationalist mass movement. Discouraged, betrayed, distrustful of these leaders, the masses dropped away from organized revolutionary activity. In fact, most of the CPUSA’s Black members also quit, aware too late that they had been led into betrayal. This was a brilliant victory for pro-imperialist integrationism within the mainstream of New Afrikan politics. But at the grassroots the anger of the oppressed still held. The week that Italian troops began occupying Addis Ababa, angry crowds in Harlem drove many Italian vendors out of business. Italian bars were attacked. Inside the New York U.N.I.A. angry nationalists removed Captain A.L. King from the leadership because of his complicity in the betrayal of their movement. None of this represented any victories against imperialism. What they showed, however, is that the grass-roots, although unable to stop their leaders from frustrating their desires, were at least determined to take care of business on their own ground.

Footnotes

(1). MARK NAISON, “Marxism and Black Radicalism in America: The Communist Party Experience”, Radical America, May-June 1971.

(2). NELL PAINTER & HOSEA HUDSON, “Hosea Hudson: A Negro Communist in The Deep South”, Radical America, July-August 1977.

(3). JAMES W. FORD & HARRY GAINES, War in Africa, N.Y., 1935, p. 28-29.

(4). AGNES SMEDLEY, Battle Hymn of China, N.Y., 1943, p. 108-109.

(5). AGNES SMEDLEY, The Great Road, N.Y., 1972, p. 333.

(6). FORD & GAINES, p. 29.

(7). DENNIS MACK SMITH, Mussolini’s Roman Empire, N.Y., 1976, p. 78-81.

(8). Ibid.

(9). Ibid.

(10). BRICE HARRIS, JR., The United States and the Italo-Ethiopian Crisis, Stanford, 1964, p. 44.

(11). SMITH, p. 87.

(12). JOHN P. DIGGINS, Mussolini and Fascism: The View From America, Princeton, 1972, p. 287-312.

(13). Ibid.

(14). Ibid.

(15). Ibid.

(16). SMITH, p. 307.

(17). CLAUDE MCKAY, Harlem: Negro Metropolis, N.Y., 1940, p. 200-201.

(18). DIGGINS, op. cit.

(19). Congressional Record, 74th Congress, 2nd Session, Vol. 80, Pt. 1, p. 2219-2221.

(20). WILLIAM R. SCOTT, “Black Nationalism and the Italo-Ethiopian Conflict 1934-1936”, Journal of Negro History, 1977, p. 118-134.

(21). Negro Liberator, March 15, 1935.

(22). Ibid.

(23). Ibid.

(24). FORD & GAINES, p. 30-31.

(25). MARK NAISON, Communists in Harlem During the Depression, N.Y., 1983, p. 155, 175.

(26). Negro Liberator, Sept. 2, 1935.

(27). VITTORIO VIDOTTO, The Italian Communist Party From Origin to 1946, Bologna, 1975, p. 314-322.

(28). Ibid.

(29). MCKAY, p. 189.

(30). Negro Liberator, March 15, 1935.

(31). NAISON, p. 196.

(32). MAO TSETUNG, On Protracted War, Peking, 1967, p. 3.

(33). FORD & GAINES, p. 28-29.

(34). On Protracted War, p. 20-21.

(35). SMITH, p. 81.

(36). HARRIS, JR., p. 140-142.

(37). NAISON, p. 196.