“Well, if the Blacks, and the Puerto Ricans, and the Chicanos and the Indians all get what they want, then there won’t be any United States...”

-- Oregon high school student questioning a Cherokee speaker from the American Indian Movement

So the reawakening of anti-colonial struggles here within the continental Empire in the 1960s was still ideologically unaware. It was a situation in which oppressed peoples went through rapid changes, trying and growing beyond different approaches and organizations, as cities burned and U.S. imperialism was thrown on the defensive. The oppressed started rediscovering their true situation, their own heritage, and the reality of their Nationhood. There were four main characteristics to those ‘60s movements:

1. They rapidly evolved toward armed struggle, with self-defense leading to armed organizations. Anti-government violence had mass approval and participation.

2. Awareness of separate nationhood grew--of not being part of the U.S. oppressor nation. This was seen in the re-examination of culture, in language, religion, dress, and the arts. Sovereignty over the land became a key concept.

3. National liberation struggles here were not seen as isolated to themselves, but as parts of a world revolution of the oppressed. People were influenced by India, Ghana, Algeria, Cuba, Vietnam, and many other peoples struggles. Crazy Horse and Ho were both seen as heroic teachers. Socialism was introduced as an alternative to the “American Way.”

4. The urban movements were in most cases under the class leadership of the petter bourgeoisie and the lumpen. Which meant that their political programs embodied an ambivalent, “love-hate” relationship towards imperialism. Even the most militant organizations were amalgamations of those who were fighting for liberation and those who, whatever thought they were doing, were fighting for a share of Babylon.

The national movements did not reach a proletarian viewpoint. This limitation undermined the great advances of the ‘60s movements. Even among those who picked up the gun, driven by anger and need for change, even within revolutionary organizations, this covered-over ambivalence helped create setback after setback. Recently, for example, arrests after an abortive N.Y. expropriation were followed by the defection to the Government a number of fighters and supporters of the RATF (Revolutionary Armed Task Force), most notably supposed “BLA” members Peter Middleton and Tyrone Rison. Both have been publicly denounced as traitors. But to see them just as unexplained betrayals of no known origin is less than useful. They have roots within the movements unresolved character. Folks should see that a Tyrone Rison and a Peter Middleton are legitimate descendants of Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS STAGE OF ANTI-COLONIAL STRUGGLE

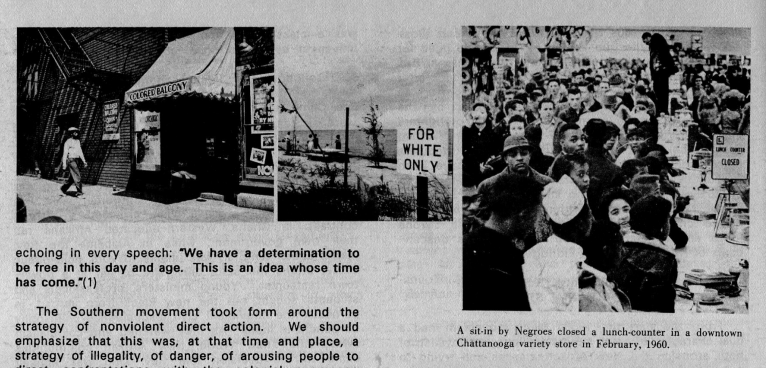

From the start the 1960s Black movement had a dual character, of being both rebellious and loyalist, of both arousing the New Afrikan masses and trying to restrain them, of being an anti-colonial movement with neo-colonial views. The Southern Civil Rights Movement that opened up in the 1960s was a clear example of this dual character. It was a movement largely led by ministers and other New Afrikan community leaders, committed to non-violence and with a moderate program of desegregation. It was explicitly Christian and pro-Amerikan in its outlook. Liberal whites were not seen merely as allies but as “brothers” and “sisters”. Yet the student sit-ins that began on February 1, 1960, in Greensboro, N.C., rocked the U.S. Empire.

The Southern Civil Rights struggle was a movement that defied and exposed colonial power The women and men of that young movement were consciously part of the world anti-colonial rising. To see this fully we have to deal with the class nature of the movement. While the Southern Civil Rights movement drew support from all classes of the Nation, its young leaders and activists were primarily from the petty-bourgeoisie. most were college students. Theirs was a class and a generation that was profoundly influenced by the world anti-colonial transformation.

Throughout the 1950s, national liberation movements had risen against the European colonial powers. Red China and the Democratic Republic of vietnam were successful. India in 1950, Ghana in 1957, and Algeria in 1962 had won self-government. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King were guests of Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah at Ghana’s independence ceremony on March 6, 1957. Rev. King was a world figure because of the Montgomery, Ala. Bus Boycott of 1956. Their visit provided a striking contrasts: in Ghanam Western-educated Afrikans ran their own government, while in Alabama the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was unable to vote, hold public office, attend the state university, or eat at a downtown restaurant. Young ministers, professionals and students sought out the new ideas from abroad, in particular the non-violent civil disobedience philosophy of Gandhi in India. As they watched anti-colonialism sweep the Third World, New Afrikan communities came to the decision that Rev. King was himself echoing in every speech: “We have a determination to be free in this day and age. This is an idea whose time has come.”(1)

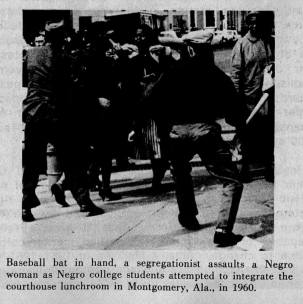

The Southern movement took form around the strategy of non-violent direct action. We should emphasize that this was, at that time and place, a strategy of illegality, of danger, of arousing people to direct confrontations with the colonial oppressor. Whether it was sitting-in at a segregated lunch counter or bus station, or defying court orders to march on a county courthouse, the movement deliberately broke the colonial law. If the institutionalized fear of settler violence had kept many from protesting their oppression before, now the Sit-In movement promised to fill the jails. Young and old pushed toward police lines, no longer willing to be stopped by settler terrorism. The illegal sin-ins spread from Greensboro to cities throughout the South, with some 3,600 arrests within the year.

Inevitably the anti-colonial struggle moved toward a higher level, growing beyond this initial stage of non-violent civil rights protests. Non-violent civil rights strategy was tried and then discarded by the New Afrikan masses, who found that it was a failure, incapable of forcing an entrenched settler-colonial regime to change. Albany, Georgia in 1961-1962 was the decisive test, Despite nine months of illegal sit-ins and marches with over 1500 arrests locally, national publicity, statements of support by a bipartisan collection of U.S. Senators and Governors, together with the presence of settler ministers, rabbis, and students from all over the North, the Civil Rights movement was unable to win anything, even token desegregation of public facilities. Lerone Bennet has written that “Albany, by any standard, was a staggering defeat for King and the freedom movement.” King was finally forced to leave the city by the angry local movement leadership.

The Southern movement strategy of non-violent mass pressure, of filling the courts and jails, disrupting the normal business of public places, completely failed. The liberal New Republic commented: “Once the goal was to fill the jails. But the Albany City Jail, which had working agreements with fortresses in neighboring counties, proved a bottomless pit. Not since Albany has anyone taken Rev. King literally when he has talked of filling the jails of the South.”(2) Over thirty Southern police departments sent officers to Albany to be trained in smothering Black protests. A suddenly famous Albany Police Chief Pritchett was flown North by the Ford Foundation to address a top-level seminar for police chiefs. And in Harlem, Minister Malcolm X was pointing out the true meaning of the Albany defeat.

Albany represented the surfacing of a political crisis. The Freedom Movement had started millions of New Afrikans towards liberation, and yet its widely proclaimed strategy of non-violent protest was unworkable. The creative result of this contradiction was already being born among the people themselves, as in the Albany struggle. When Rev. King led 250 signing marchers toward the Albany City Hall on December 17, 1961, the arrests were watched by a curious crowd on the sidelines. hidden within that crowd were the members of two youth gangs, who had secretly come on their own initiative to defend the marchers if the arresting police got violent.(3) By the next July, militant youth had left the sidelines and taken the center stage. After a woman was badly beaten by a sheriff’s deputy while attempting to deliver food to activists in a rural prison camp, two thousand New Afrikan youth took over streets and whole blocks in a night-long uprising on July 25, 1962. Police cars were stoned, and eventually pulled out of the ghetto. The stage of protests was leading to the stage of rebellion.

THE BULLET AND THE BALLOT

The impending failure of the non-violent Civil Rights movement was primarily a crisis for two classes--for the U.S. bourgeoisie and the Black petty-bourgeoisie. In response to the threat of liberation war, the U.S. Empire drew the colonial petty-bourgeoisie closer to itself as a shield while enacting a revamped neo-colonial program to pacify the masses. Civil Rights became the U.S. Government’s official pacification program, while the hollow shell of the dying Civil Rights movement was itself taken over by U.S. imperialism to be used against the deeper anti-colonial rebellion.

By the time of President Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, the imperialist State had mobilized behind its new counter-insurgency program-the Ballot and the Bullet. That strategy was a watered down replica of the original Black Reconstruction of the 1860s and 1870s. It reminds us of Marx’s’ comment that all great events in history happen not once but twice--”the first as tragedy and the second as farce.” Under its new strategy imperialism stepped up its search to destroy missions in the New Afrikan communities. Not only to violently neutralize militant leaders and organizations as a danger per se, but to clear the way for the Empire’s hand-picked Civil Rights leadership to command the struggle.

This loyalist leadership directed the protest movement back around towards neo-colonialism as a goal towards begging to be accepted into Babylon as citizens. Instead of mass struggle--which shoots off in rebellious directions--the Empire wanted its loyalist Civil Rights leaders to convince New Afrikans that voting in U.S. elections should be their main weapon. And that their basic philosophy should be to look up to the Federal Government as New Afrikan peoples’ special protector and economic provider. To the extent that such a loyalist Civil Rights movement influenced them, New Afrikans would be disarmed in all senses of the word. So in the U.S. Empire’s 1960s strategy, persuading New Afrikans to get tied up in U.S. bourgeois politics and shooting down those who still dissented were joint parts of the same counter-insurgency plan--the ballot and the bullet.

At Albany, for example, where the non-violent movement had taken on a mass character that might lead to rebellion, and were the embattled local organizers had thrown off the restraining national Civil Rights leadership, the Kennedy Administration struck at the grassroots. President John F. Kennedy told the press that he thought that the city government should work out a negotiated agreement. His brother, U.S. Attorney-General Robert Kennedy, held a late-night meeting on Albany with NAACP President Roy Wilkins, Mel Wulf of the ACLU (American Civil Rights Union), Walter Faunteroy of SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference), and other Civil Rights leaders. They were told that for the first time in the South, teams of FBI agents had been sent into Albany to set up Federal criminal indictments. Frontpage newspaper articles in early August 1962 portrayed the Government as sympathetic to the Albany Freedom Movement. This was just a deception.(4)

Meanwhile in Albany itself, thirty-five FBI agents had interviewed naively cooperative Civil Rights activists. Fifty-eight New Afrikans were then subpoenaed to appear before a Federal grand jury in Macon, the first Southwestern Georgia grand jury called over Civil Rights activity. But to their surprise they found that they and not the racists were the target. The imperialist strategy called for little visible police violence on the main streets of Albany itself, where the international media might publicize it. everywhere outside the city limits, however, in the surrounding towns and rural areas, police suppression of the movement intensified.

In nearby Americus, Georgia, on August 8, 1961, three SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) field workers watching a demonstration were attacked by Americus police. After being tortured, the three were charged with intent to murder and insurrection (death penalty offenses) and held without bail for three months. A protest demonstration the next day was violently smashed by a posse made up of Americus police, deputized Klansmen, county police, and state troopers. New Afrikan elderly and teenagers alike were severely clubbed and burned with electric cattle prods. On that same day, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy was personally holding a Washington press conference to announce that his Macon, Georgia grand jury had indicted nine Albany Civil Rights workers for organizing a boycott of a settler grocery store. A U.S. Justice Department spokesman, in answer to questions from the surprised newsmen, said: “There is no evidence of police brutality in Americus.”

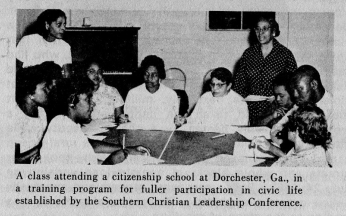

Young people come in busloads to line up at the registrar’s office in Macon, Ga. In one year, with the help of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Bibb County Citizens’ Negotiation Committee doubled Negro voter-registration.

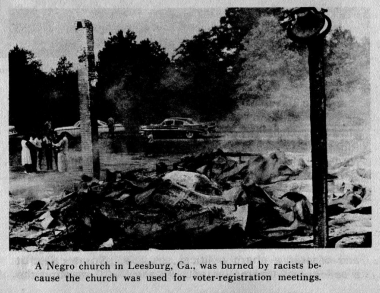

Eight of the nine Civil Rights workers were convicted after a token trial in which the U.S. Attorney struck off every potential New Afrikan juror, resulting in an all-settler jury. Sentences ranged from five years suspended up to two years in prison.(5) In coordination with the FBI operation, the local Klan blew up four Albany New Afrikan churches. The U.S. counterinsurgency strategy on the one hand allied with the “moderate” national Civil Rights leadership and portrayed the Government as supporting democratic change, while on the other using unofficial terrorism to intimidate the New Afrikan community, and repressing the Movement Infrastructure with direct police violence and FBI frame-ups. While everyone thought of the national Civil Rights leadership and the Klan as total opposites, both were coordinated arms of the sophisticated, U.S. counter-insurgency campaign. In his speech to the 1963 March on Washington, SNCC Chairman John Lewis was going to charge: “It seems to me that the Albany indictment is part of a conspiracy on the part of the Federal Government...” That line was censored out of his speech at the united insistence of the rest of the Civil Rights leadership.(6)

Even before Albany, at the beginning of the Sit-in movement, the development of Civil Rights politics was being influenced by counter-insurgency strategy. At the June 1961 SNCC Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, Tim Jenkins made a proposal that the movement turn away from militant confrontations and illegal protests--and instead focus its energies on voter registration. This proposal actually originated with the Government. Burke Marshall, Assistant Attorney-General for Civil Rights, and Presidential “minorities” advisor Harris Wofford, together with Stephen Currier of the Taconic Foundation and the representatives of the Field Foundation, had worked out the proposal in secret meetings with Jenkins. The latter was then the Black Vice-President of the liberal National Student Association (NSA), the college student governments. While Jenkins has always denied working for the CIA within the Civil Rights Movement, at that time the CIA was using the NSA as its main front for international student work. Some NSA officers have admitted covertly cooperating with the CIA, which was supplying a good part of the National Student Association budget.

The Jenkins proposal shocked many young activists, and created a sharp political struggle. Some called it a sell-out of the movement. At the SNCC meeting the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. intervened as a moderator, listening sympathetically to the militants for hours, finally getting a compromise proposal passed in which SNCC would approve both government-sponsored voter registration and militant direct action. King sincerely spoke for the importance of working with the U.S. Government. What the students (and the New Afrikan community) didn’t know was that the first secret deal was already being made to pull away from mass struggle.

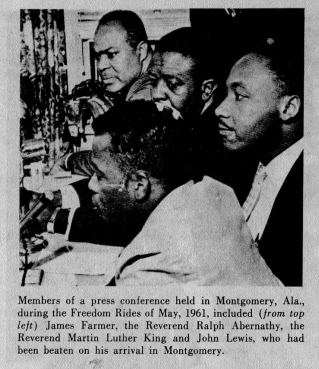

In May 1961 the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) had launched the Freedom Rides, a national attack on segregated interstate transportation. Integrated teams took on Greyhound and Trailways buses through the Deep South, refusing to sit in the back of the bus or limit themselves to “colored” waiting rooms. A frenzy of hatred gripped the settler South as an amazed world watched. The first Greyhound bus was stopped and burned by a settler mob outside Anniston, Alabama. The second reached Birmingham, where a KKK assault organized by the FBI sent two Freedom Riders to the hospital.

Throughout the South mobs of settlers, coordinated by police and the FBI, violently attacked Freedom Riders. In Montgomery, after a mob of one thousand settlers injured Euro-Amerikan reporters and John Siegenthaler, a White House aide, seven hundred U.S. Marshals were flown into town to maintain order. The Kennedy White House was concerned that this orgy of settler violence, front-page news around the world, would undercut their plans to pacify the ghetto. SCLC and Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. also called the high-risk Freedom Rides “unfortunate.” King surprised his public by refusing to go himself. Robert F. Williams telegrammed Rev. King in anger: “You’re a phony. Gandhi was always in the forefront, suffering with his people. If you are the leader of this non-violent movement, lead the way by example.”

So after U.S. Attorney-General Robert F. Kennedy was turned away when he appealed for a “cooling-off period,” the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. proposed a “temporary lull” in the Freedom Rides instead. Which was the same thing. Robert F. Kennedy had convened a secret meeting with the Civil Rights leadership. there the President’s brother had explained why the Administration needed an end to the violent confrontations. He said that the Government and the Civil Rights leaders really wanted the same things. Both their interests would be satisfied not by militant struggles but by registering millions of New Afrikan voters in the South. New Afrikan voting would integrate local Southern government, prevent “riots”, and give the liberal Democrats extra votes to help the White House.

If the Civil Rights leadership would quietly phase out the freedom rides in favor of Government-sponsored voter registration campaigns, Kennedy promised, he would give their organizations an initial $250,000, and get the Interstate Commerce Commission to rule in the Fall that segregation of bus, train and airline travel was forbidden. Of course, Kennedy couldn’t give them the money directly. He arranged for the Taconic Foundation, whose settler President Stephen Currier became a part of the Civil Rights leadership, and the Field Foundation to divide the money up between the NAACP, SCLC, SCNN and CORE. Kennedy promised them as much money as they needed to fight Robert Williams, Malcolm X and other nationalists.(7) The Civil Rights leadership accepted the imperialist program. At the same time, Andrew Young was to be added to King’s SCLC staff. Young was working directly for Field Foundation, in charge of spending $100,000 in the south persuading the movement to concentrate on voter registration projects.

THE YEAR OF COUNTER-INSURGENCY

The decisive year for imperialism’s new policy was 1963, when the Empire moved into a stepped-up neo-colonial campaign. New Afrikans were reluctantly, over the bitter protests of the settler masses, conceded some bourgeois democratic rights in the South. These rights were in the form of second-class (“minority”) Empire citizenship. Even so the change was considerable. Within the space of a few years New Afrikans could both shop and work at downtown department stores, be policemen and sheriffs, shift from Black colleges to major universities, elect Black officials to local government, and for awhile play at being real citizens of Great Babylon. This was the final step in a process: the change that had earlier forced paper U.S. citizenship on the Indian nations in 1925, and Hawaiians and Puerto Ricans as well.

In the 1960s the Black petty-bourgeoisie emerged in a key role, as an intermediary class between the U.S. bourgeoisie and the New Afrikan masses. The petty-bourgeoisie as a world class has a vacillating and intermediary character, neither owning the means of production as does the bourgeoisie nor supporting society through its labor as as does the proletariat. But in an oppressed nation the petty bourgeoisie is, as a whole, an intermediary class between people of its own nation and the occupying imperialist bourgeoisie. This is a relationship involving both conflict and accommodation.

One reason that imperialism’s counter-insurgency offensive was so effective was that it used a vulnerability in the ideological armor of the New Afrikan movement. Because of their role as an intermediary class, oriented to imperialism, the petty-bourgeois leadership of the struggle were fixed on the idea that the Federal Government was the answer to New Afrikan peoples’ problems. Not the enemy, but the reluctant saviour. Despite all the publicly professed faith in the “decent majority” of settlers finally waking up to justice, no one in the Civil Rights leadership (or on the streets) actually believed this nonsense. Rev. King himself, after the 1962 KKK-FBI bombings of Albany churches, wrote white Southerners off: “The Negro stands little chance, if any, of securing the approval, consent, or tolerance of the segregationist white South.” It was the Federal government that was seen as the big power which, when finally cajoled or pressured into action, would give equality to New Afrikan people--if necessary over the objections of white people. In Albany the students marched towards jail invoking President Kennedy in song:

“Oh, Mr. Kennedy, take me out of misery.

Freedom’s coming and it won’t be long.

Look at segregation, look at what it’s done to me

Freedom’s coming and it won’t be long.”

Martin Luther King himself exemplified this contradiction. King rejected political violence not only on philosophical grounds, but because he felt it impractical for his struggle. like many others of his class, King was so convinced of the superiority of White Amerika that he didn’t believe that armed struggle against it could ever win: “... internal revolution has never succeeded in overthrowing a government by violence unless the government had already lost the allegiance and effective control of its armed forces. Anyone in his right mind knows that this will not happen in the United States.” Again and again he emphasized his view that Black revolt could not win against settlers: “We have neither the techniques, the numbers, nor the weapons to win a violent campaign.” This has been the fundamental viewpoint of the Black movement on their relationship to the oppressor nation.

King struggled to build close ties to the White House, and to persuade the government to support the freedom movement. In return he felt himself bound to support the U.S. Government in many ways. While Rev. King regularly disregarded the state court injunctions and rulings against demonstrations, he thought it wrong to disobey a Federal court order even if it was unjust. Not once in his political career would he ever break a Federal law or court order, a position that he admitted to his associates but tried to conceal from the public.(8)

King could honestly not comprehend the thinking of Malcolm X and other militant nationalists. On several occasions Malcolm had tried to bridge the gap; in both 1957 and 1960 he had invited King to speak at Muslim events. On the latter occasions King had been invited to address the 1960 Muslim Education Rally in a large armory in New York City. King always declined. He told a friend: “They have some kind of a strange dream of a Black nation within the larger nation. At times the public expressions of the this group have bordered on a new kind of race hatred and an unconscious advocacy of violence.” King at that time could not understand not wanting to be part of the “American Dream.”

At the same time Rev. King was launching new Civil Rights campaigns and criticizing the Kennedy Administration, which was clearly hoping to stall off the Civil Rights reforms indefinitely. He wrote: “If tokenism were our goal, this administration has adroitly moved us toward this accomplishment. But tokenism can now be seen not only as a useless goal, but as a genuine menace.” In the spring of 1963 SCLC began its major Birmingham, Alabama campaign, designed to prove that King’s non-violent direct action strategy could still win.

It was there that the alliance between the U.S. bourgeoisie and the Black petty-bourgeoisie protest leadership was firmly cemented. For Birmingham--a steel and coal industrial center that was a terroristic fortress of segregation--was the Albany struggle all over again. The local settler-colonial regime stood fast, while police clubs, dogs, and high-pressure water hoses battered the crowds of marchers. Birmingham held the world’s attention, and its rabid Police Commissioner “Bull” Connor became a world symbol of Americanism. On “Project C Day,” May 2, 1963, six thousand new Afrikan children from age six up marched, singing in wave after wave, on City Hall. 960 of them were arrested as the settler police ran out of paddy wagons, and crowds of seven and eight year old girls chanted “Freedom!,” “Freedom!” Still there was no softening, no concessions by the local settler government. By May 7, 1963 over two thousand demonstrators were in jail, with no resolution in sight.

It was on that afternoon that the situation started turning. New Afrikan demonstrators, attacked by police, began fighting back. Three thousand New Afrikans fought police with barrages of rocks and bottles up and down Birmingham’s business district, while the settler Chamber of Commerce watched from their windows high above in shock. What non-violent marches couldn’t accomplish, the first spectre of rebellion did. The White House was galvanized into action. President Kennedy had has Cabinet members call their Birmingham corporate friends and push for a negotiated settlement. Ford Motor Company, Royal Crown Cola, Birmingham Trust National Bank, U.S. Steel, Tennessee Coal & Iron and other big corporations started demanding an immediate settlement.

Within two days the city and the protest movement had reached a milestone agreement, desegregating department stores in downtown Birmingham. Hoping that the breakout of the masses could be smothered in publicity over the desegregation pact, President Kennedy praised the settlement in a speech and offered Federal guarantees on its implementation. The U.S. bourgeoisie had finally intervened to give the non-violent Civil Rights movement a boost, to save it from another Albany-type failure, and to short-circuit mass confrontations which were leading to rebellion.

But on the night of May 10, 1963 new fighting broke out in Birmingham, on a far larger scale. Late that evening the home of Martin’s brother, A.D. King, was bombed. An hour later the New Afrikan-owned Gaston Motel was also dynamited. As news spread a rebellion broke out, with thousands of New Afrikans seizing a nine block area until 5 a.m. Police cars were trashed, an officer stabbed and others injured by stoning. Birmingham newspapers the next morning ran a front-page photo of Police Chief Inspector Haley, his face bloody and dazed. Settler-owned stores were burned while angry crowds drove off firemen. SCLC leaders were onlookers, powerless to stop the rebellion.

The Birmingham rebellion absolutely convinced the government that even larger reforms were needed to dampen the fires of revolt. As King said: “The sound of the explosion in Birmingham reached all the way to Washington.” On June 11, 1963 President Kennedy, addressing the Empire, called for Congress to pass the now-historic Civil Rights Act. The failure of the non-violent Civil Rights movement and the spreading breakout of anti-colonial struggle by the New Afrikan masses, forced the imperialism government and the Black petty-bourgeois protest leaders to wake up and admit how much they needed each other, to back each other up. This was the true meaning of the March on Washington, which on August 28, 1963 brought 250,000 persons to Washington as a pacified backdrop for King’s “I Have A Dream” speech.

The March on Washington was a pro-Government propaganda exercise, marking imperialism’s takeover of the Civil Rights movement. While the New Afrikan masses were angry and moving into violent rebellion, their organized leaders were trying to pacify them into inactivity. It was Malcolm X who first exposed the March on Washington, echoing the questioning that was also growing at the grassroots of the freedom movement.

“When Martin Luther King failed to desegregate Albany, Georgia, the civil-rights struggle in America reached its low point. King became bankrupt, almost, as a leader. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was in financial trouble; and it was in trouble, period, with the people when they failed to desegregate Albany, Georgia. Other Negro civil-rights leaders of so-called national status became fallen idols. As they became fallen idols, began to lose their prestige and influence, local Negro leaders began to stir up the masses. In Cambridge, Maryland, Gloria Richardson; in Danville, Virginia, and other parts of the country, local leaders began to stir up our people at the grass-roots level. This was never done by these Negroes of national stature. They control you, but they have never incited or excited you. They control you, they contain you, they have you kept on the plantation.

.......

“...This is what they did with the March on Washington. They joined it. They didn’t integrate it, they infiltrated it... And as soon as they took it over it ceased to be hot, it ceased to be uncompromising. Why, it even ceased to be a march. It became a picnic, a circus... They controlled it so tight, they told those Negroes what time to hit town, how to come, where to step, what signs to carry, what song to sing, what speech they could make, and what speech they couldn’t make; and told them to get out of town by sundown. And every one of those Toms was out of town by sundown.”(9)

The No. 1 purpose of the March was to tie up militant activity in the communities, to defuse youth by misdirection, getting local organizers all wrapped up during the “hot summer” in organizing busloads for the super-event in Washington. The other main purpose of the March was to publicly applaud the Kennedy Administration, and to picture settler liberalism as the ideology of justice for New Afrikans. On June 22, 1963, Stephen Currier of the Taconic foundation, who was now the man who controlled black protest funds, led the ”Big Six” Black leaders in to meet with President Kennedy and his associates at the White House. When Kennedy worried about the March because of the risk of some real struggle breaking out, Pullman Union leader A. Philip Randolph answered: “The Negroes are already in the streets. It is very likely impossible to get them off. If they are bound to be in the streets in any case, is it not better that they be led by organizations dedicated to civil rights and disciplined... rather than to leave them to other leaders who care neither about civil rights nor non-violence?” Currier, Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy agreed, and President Kennedy said that the Government would support the March.

Less than a month afterwards, Stephen Currier promised the Black petty-bourgeois leaders $1.5 million, with $800,000 handed out at the meeting. Militant SNCC got the smallest share by far--only $150,000--with the agreement that their money would be “sharply upgraded” later if they became more obedient.

The March itself had no struggle or even protest about it. Confused marchers were handed out pre-printed picket signs (mostly made by the United Auto Workers Union) with only Government-approved slogans. No militancy, attacks on the Government, or spontaneous activity was tolerated. The speech by SNCC Chairman John Lewis was ordered censored and rewritten from initially saying “we cannot support the Administration’s civil rights bill” to the reverse: “True, we support the Administration’s civil rights bill.” Stricken out were the SNCC’s threats of armed struggle: “The next time we march, we won’t march on Washington, but we will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did.” After being reduced to polite spectators just listening for hours to pro-imperialist speeches, the crowds were ordered to leave town as soon as possible. The contempt that the March leaders had for the New Afrikan people--and how much they wanted to break them of all spirit and self-respect--can be seen in the confession of Bayard Rustin, the March’s chief organizer.

"You start to organize a mass march by making an ugly assumption. You assume that everyone who is coming has the mentality of a three-year-old. You have to tell them every little detail of what they should do... even how to leave when the March ended."(10)

Before the March the Black protest leaders were scared, and had to tell President Kennedy that the masses were out of control, in the streets. After the March the leaders thought they could safely laugh at their own people as having “the mentality of a three-year-old.” But while they new counter-insurgency campaign took over the movement, the anti-colonial rebellion continued to deepen and spread. The bourgeoisie, understanding this, continued to support harmless protest activity, publicizing the chosen leaders and lavishly funding their activities. Martin Luther King tried to get the settler public to understand how civil rights protests were actually helping to restrain the Black Revolution, and were thus in settler interests:

“It is not a threat but a fact of history itself that if an oppressed people’s pent-up emotions are not non-violently released, they will be violently released. So let the Negro march. Let him make pilgrimages to city hall. Let him go on Freedom Rides. And above all, make an effort to understand why he must do this. For if his frustrations and despair are allowed to continue piling up, millions of Negroes will seek solace and security in Black nationalist ideologies.”

The U.S. bourgeoisie had learned that New Afrikan Revolution was much closer than they thought, and that drastic neo-colonial reforms were needed to undercut the mass rising until it had run its course. Further, that the Empire needed to take over and sponsor the unsuccessful non-violent protest movement, needed to make it look more successful for the New Afrikan people. The Civil Rights leadership and their organizations were put on imperialism’s payroll; pushed every day by the imperialist media just like breakfast cereal or deodorants.

The dual role of the New Afrikan petty-bourgeoisie as a vacillating and intermediary class was also being played out, as they ran back and forth allying with both sides. They called for mass protests against oppression, but only so that they could negotiate with the Government to end the protests. Many perceptive people had seen after Birmingham that non-violent protests politics could not even pressure the Empire. Only the threat of rebellion had the power to force concessions from imperialism. This was to become important as the movement developed.

MALCOLM AND REBELLION

The years 1964-1966 were ones of rapid transition, as the New Afrikan Nation moved towards the stage of revolution. Ghetto rebellions spread, becoming common for the first time. The anti-colonial struggle was taken up by the masses and ignited across the continent. In the rising ideological debate over what path New Afrikans should taken, Malcolm X became the central figure leading the Nation towards liberation. His political lessons were a guide for starting the New Afrikan revolution.

These developments were due to an internal dynamic, which was itself part of the larger dialectic of oppressed and oppressor nations within the framework of the settler Empire. Major differences exist within the settler Empire over imperialism’s neo-colonial program. Most settlers have always believed that neo-colonialism is too good for New Afrikans. While the U.S. Big Bourgeoisie and the liberal intelligentsia backed President Kennedy’s Civil Rights Act, reactionary elements of the local bourgeoisie wanted to simply repress the anti-colonial rising without reforms or concessions. In this the reactionaries had overwhelming support from the settler masses. This was true not just in the Deep South, but in all regions--as true in Chicago as it was in Jackson.

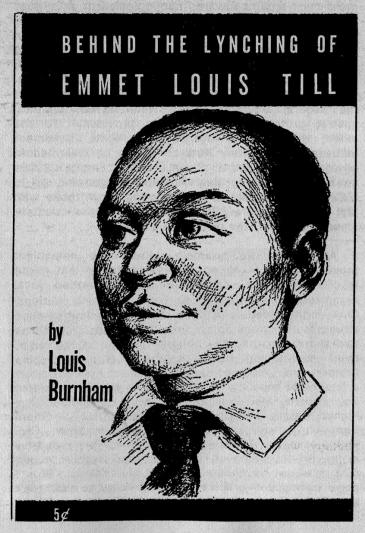

Much of the state apparatus, including the FBI, was openly allied to the reactionary elements. So in Birmingham and elsewhere, the FBI worked with the KKK to answer the March on Washington with continued terroristic bombings and assassinations. The timing of these attacks only further angered the New Afrikan masses and exposed the futility of Civil Rights politics. Even before his neo-colonial legislation enacted by Congress, on November 22, 1963 President Kennedy himself was removed by his imperialist opponents. Malcolm X penetrated the neo-colonial crisis:

“Now that the show is over, the Black masses are still without land, without jobs, and without homes... their Christian churches are being bombed, their innocent little girls murdered. So what did the March on Washington accomplish? Nothing!”(11)

Unable to get over with the awakening New Afrikan masses, caught in the fire between settler reaction and the liberation struggle, the existing Civil Rights leadership broke down. While non-violent demonstrations were still the predominant form of organized activity, non-violence was finally admitted to be a only a tactic of weakness. Armed self-defense became an integral part of Southern Civil Rights work. In 1965 the Deacons for Defense, an armed defense guard for Civil Rights activity, was formed in Louisiana and soon spread to other Southern states. The historic Meredith March through rural Mississippi during June 1966 showed the contradictions: during the day the March stressed the standard non-violent protests, complete with prayer rallies, while at night the March defense guard had to drive Klan snipers off in exchanges of gunfire.

That Mississippi March was also notable for its display of the Civil Rights leadership’s fragmentation and flailing about. James Meredith, the first New Afrikan student at the University of Mississippi, was conducting a one-person March to Jackson, the state capital, to symbolically establish the right to free movement without gear. That was a direct challenge to the settler power. On June 6,1966 as Meredith was crossing the Tennessee border into MIssissippi, he was wounded by a shotgun attack in broad daylight. There was national outrage over the casual brazenness of the attack.

The next day Civil Rights leaders and activists flew in from all over the U.S., as the movement publicly vowed to continue Meredith’s March through Mississippi to its conclusion. Martin Luther King, SNCC’s Stokeley Carmichael, CORE National Director Floyd McKissick and Mississippi NAACP Director Charles Evers, led the hundreds of defiant marchers into Mississippi. But at the starting rally in Memphis, Stokeley Carmichael roused the crowd with his militant version of Civil Rights politics: “I’m not going to beg the white man for anything I deserve. I’m going to take it.” Not to be outdone in rhetoric, CORE’s McKissick said that since America’s symbol was the Statue of Liberty, “They ought to break that young lady’s legs and throw her into the Mississippi.”

As the marchers slowly crossed Mississippi the physical harassment, police pressure and danger grew. SNCC’s Willie Ricks and Carmichael began popularizing the slogan Black Power. SCLC people were still shouting “Freedom Now” as a chant, while SNCC people started chanting “Black Power” instead. More and more marchers refused to sing the line “Black and White Together” in the movement song “We Shall Overcome.” The militant mood was so strong that even King’s associate Rev. Hosea Williams, at the Greenwood rally, got carried away and shouted to the crowd: “Whip that policeman across the head!” Trying to rescue SCLC from Williams’ rhetoric, King rose to say diplomatically, “He means with the vote.” Carmichael yellowed: “They know what he means.” In Yazoo, King was booed as he tried to lecture the marchers on non-violence.

In Philadelphia and Canton, Mississippi the March was met with violence. Rev. King tried to hold a memorial service in Philadelphia for three slain 1964 Mississippi Summer workers - Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner - but it was broken up by a Klan mob. The settlers threw fireworks into the assembled marchers, and then started physically assaulting people. New Afrikan youth fought back, which temporarily cooled the violence. But that night the camped marchers were again attacked, this time by KKK snipers. There were four Klan attacks with gunfire that night. The Deacons for Defense, the Louisiana armed self-defense organization that had come along but had so far abided by the agreement on non-violence, began firing back. In Mississippi even pro-U.S. Civil Rights needed a military component.

Maneuvering to avoid the confrontation, King wired President Johnson pleading for Federal marshals to be sent in to protect them. The President didn’t answer. The White House was displeased at King associating with the militant Civil Rights forces. Washington agreed with the local power structure that the trouble-makers should be discouraged. At Canton, Mississippi, Stokeley Carmichael demanded that the March show how militant it was by pitching their tents against police orders. Firing their tear gas ahead of them, State troopers and Canton police routed the two thousand marchers as they were making camp. Police ran through clouds of tear gas into the panicked marchers, clubbing and whipping at will. The militant leaders could only tell people to make for the nearest church. The next day the U.S. Attorney-General said that he deplored police overreaction, but that the marchers had provoked the police.

Neither SNCC, CORE, nor SCLC could tell people what to do about these problems. By 1966 all factions of the Civil Rights leadership, from Whitney Young to Stokeley Carmichael, were desperate over their growing irrelevance as far as the masses were concerned. Andy Young of SCLC warned: “We have got to deliver results--non-violent results in a Northern city--to protect the non-violent movement.” Their problem was that the New Afrikan masses by the hundreds of thousands were voting against the Empire with Molotov cocktails, in festive uprisings that the Civil Rights leaders could not head off, control or even pretend to influence.

From 1963 to 1966 the mass ghetto rebellions, which at first so shocked White Amerika, gathered momentum. In Chicago, high school student leaders aided by local civil rights leaders led 225,000 New Afrikan students out of school on October 1963. Their total mass boycott, which showed the depth of anti-colonial unity in the larger community, demanded the ouster of segregationist School Superintendent Ben Willis. The school boycotts jumped to New York, where over 400,000 New Afrikan students joined. In Jacksonville, Florida fighting resulted in the Spring of 1964 after Klansmen shot down a New Afrikan woman in random terrorism. Jacksonville High School students evacuating from a KKK bomb threat attacked settler police and reporters. According to Federal authorities it marked the first use by New Afrikans of Molotov cocktails.(12)

Rebellions in Harlem, Brooklyn, Rochester, Elizabeth, Paterson, Jersey City, Chicago and Philadelphia in 1964, set the stage for the great Watts uprising of 1965 in Los Angeles. The Molotov cocktail was not common. In Watts the struggle lasted for days, only ending after National Guardsmen with heavy automatic weapons occupied the community. The death toll was 34, with hundreds wounded and 4,000 arrested.(13) As King, Young and Bayard Rustin toured the burnt-out area, a group of youths shouted at them, “We won!” One rebellion participant joyfully told a minister: “Every day of the riots was worth a year of Civil Rights demonstrations.” The next Summer, in 1966, there were 43 urban rebellions. Police and Guardsmen in both Chicago and Cleveland encountered sniper fire. Throughout this period there were both spontaneous mass outbreaks and also mass actions led or initiated by small cadre groups against the police. Revolutionary nationalists and fighters of various political views, many of whom had never been in the CIvil Rights movement, were making their presence known.

When the New Afrikan ghettos rose in rebellion, Malcolm X was the only major figure whose leadership was actually acknowledged by the people in the streets. A 1964 N.Y. Times report on U.S. Government concern over Malcolm said: “Malcolm is regarded as an implacable leader with deep roots in the Negro submerged classes. At one point in the Harlem riots, the same people who booed Bayard Rustin and James Farmer of CORE shouted, ‘We want Malcolm.’”

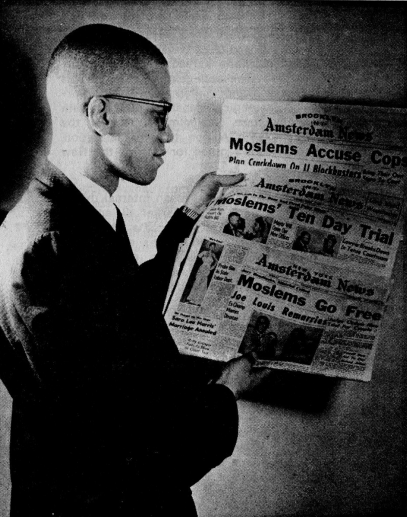

Unlike most of the various Civil Rights leaders, whether militant or puppet, Malcolm X was not a creation of foundation grants, liberal churches, the imperialist media or the Black establishment. Nor was Malcolm X someone who had soared meteor-like into prominence because of his oratory, although he himself was unsurpassed as a public speaker. Malcolm X was a true leader of the New Afrikan people because he had put his life in their service, teaching and organizing the masses. What so many have overlooked is that Malcolm was a leader in fact not just in name; a builder, recruiter, strategist who actually started masses of people moving on the path of national liberation. When Malcolm came out of prison to the Nation of Islam in 1952, there were only four temples and less than 2,000 members. Malcolm spent years recruiting and building the N.O.I. until it has over 50 mosques and approximately 200,000 members. It was Malcolm X’s leadership that was the political rock upon which the revolutionary period was begun.

Malcolm X was the first new Afrikan leader in this century to speak primarily to the oppressed masses, and to tell the masses the complete truth as he knew it. That’s why he was a great teacher; because he believed in his people and knew that they could change the world. The electricity he created was based on that--unlike Roy Wilkins or Stokeley Carmichael or Martin Luther King, Malcolm was going to tell you what was really going on, was going to “pull the cover off” the oppressor and his flunkies. As part of this, Malcolm told the masses the truth about their own movements, about the false leaders who were created by and served the colonizer. When he learned about the corruption of his own teacher, Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm unflinchingly told New Afrika about the new situation: “Muhammad is the man, with his house in Phoenix, his $200 suits, and his harem. He didn’t believe in the Black state or in getting anything for the people. That’s why I got out.” That was unpopular, but he did it.

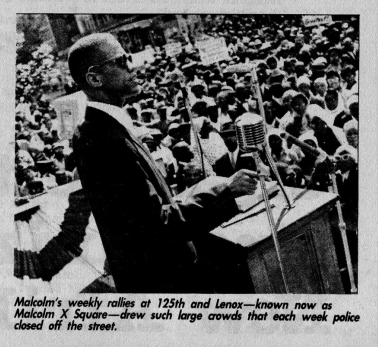

Whether it was reminding New Afrikans that they were not “Americans,” or organizing trained security units, Malcolm X was the bearer of advanced ideas. Again, not just as talk but in deeds. By the ‘60s, Malcolm’s weekly rallies at 125th St. and Lenox Ave. in Harlem were drawing so many people--many thousands--that the police had to close the streets to automobile traffic. One day Malcolm calmly told the crowd: “If you look to at the rooftops you’ll find that the white boys have the CIA and all those people with their guns on the rooftops, but next to every white man there’s a Black Muslim, so we have the situation well in hand.”(15) And near every imperialist security man there was an armed Muslim. That’s the kind of advanced leadership that Malcolm gave people. This was at a time, we should recall, when the Civil Rights leaders were always asking the police or the FBI or the U.S. Justice Department for “protection.”

Malcolm fought to get New Afrikans out of the trap of thinking that they were “minority” citizens in Amerika. Malcolm never wanted to become part of the U.S. oppressor nation, with or without Civil Rights. He thought and did his political work as an Afrikan, and as part of the oppressed world majority. His international stature was so great that Civil Rights leaders began to get the picture that they had to start talking more like him or get left out in the cold. In December 1964 two SNCC representatives visited Afrika to build international support. A written report to SNCC by them shows the surprise that Malcolm’s influence had on them:

“Among the first days we were in Accra, someone said ‘Look you guys might really be doing something--I don’t know, but if you are to the Right of Malcolm, you might as well start packing right now ‘cause no one’ll listen to you!’ Among the first questions we were continually asked was ‘What’s your organization’s relationship to Malcolm?’ We ultimately found that this situation was not peculiar to Ghana; the pattern repeated itself in every country... Malcolm’s impact on Africa is fantastic. In every country he was known and served as the main criteria for categorizing other Afro-Americans and their political views.”(16)

Malcolm’s political thought was not, as we know, a finished product. Standing head and shoulders above his contemporaries, his work was still a journey cut down in midstream. He had yet to come to grips with communism, with proletarian class ideology, although he was consciously anti-capitalistic. Malcolm’s break with Elijah Muhammad’s doctrine was a new beginning. He was not above his Nation, but was part of the fertile questioning and re-examining that characterized his times and his movement. Shortly before his death he told an interviewer: “But I would still be hard pressed to give a specific definition of the overall philosophy which I think is necessary for the liberation of the Black people in this country.”(17) Still left unanswered at his death were the practical questions of program: How New Afrikans will overcome oppression, what specific society they need to build, and who should lead them?

Footnotes

(1). DAVID L. LEWIS, King: A Critical Biography, Baltimore, 1971, p. 90. Unless otherwise indicated, this book is the general source for all quotations and background information in this section.

(2). REESE CLEGHORN, “Epilogue in Albany: Were the Mass Marches Worthwhile?”, The New Republic, July 20, 1963.

(3). Ibid.

(4). “Secret Talk in Capital On Georgia”, New York Post, August 4, 1962.

(5). HOWARD ZINN, SNCC: The New Abolitionists, Boston, 1964, p. 211-212. “The Albany Cases”, The Nation, April 20, 1964.

(6). ZINN, op. cit.

(7). Interview with member of National CORE staff.

(8). While this is made clear in LEWIS, Aldon D. Morris’ The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Change quotes Dr. King directly on this point.

(9). EL HAJJ MALIK EL SHABAZZ, “Message to the Grass Roots”, in GEORGE BREITMAN, Ed., Malcolm X Speaks, N.Y., 1966, p. 3-17.

(10). DANIEL S. DAVIS, Mr. Black Labor, N.Y., 1972, p. 148.

(11). EL HAJJ MALIK EL SHABAZZ, “God’s Judgement of White Amerika (The Chickens Are Coming Home to Roost), in BENJAMIN GOODMAN, Ed., The End of White World Supremacy, Four Speeches by Malcolm X, N.Y., 1971, p. 146.

(12). Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, N.Y., 1968, p. 35-38.

(13). Ibid.

(14). BREITMAN, Ed., p. 194.

(15). JOHN O. KILLENS in “Talking Book: Oral History of a Movement”, Village Voice, February 26, 1985.

(16). BREITMAN, Ed., p. 85.

(17). BREITMAN, Ed., p. 212.