Vietnam was a catalyst in the generalized political crisis that overtook the U.S. Empire starting in 1967. U.S. imperialism had wilfully picked Southeast Asia as the battleground for a decisive test of strength, an arrogant showdown with world socialism and national liberation. But their unsuccessful invasion brought to light all of U.S. imperialism's weaknesses and contradictions. The war awakened tens of millions of people to political life. It was a turning point, proving that a small and underdeveloped nation could defeat a large Empire, that an oppressed people guided by socialism could throw out the strongest imperialist power. Peoples War in Vietnam was a model to revolutionary-minded people throughout the world. That was even true for some Euro-Amerikan youth, who were part of a generation of dissent. For the first time in settler history revolutionary tendencies were created that looked to the leadership of the oppressed in the Third World.

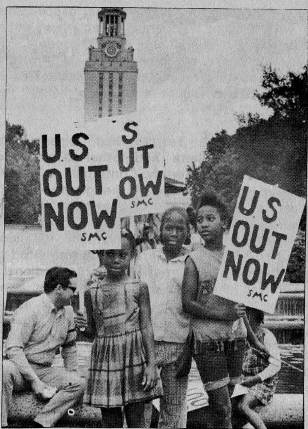

The issue of the war had an important impact on mass politics. As the Government was morally discredited and its criminal violence against the Vietnamese people understood, political violence against the Empire was legitimized. The draft suddenly connected Main Street USA to land mines, ambushed patrols, and the Tet offensive. Everyone was pushed to choose sides, to be for or against the Government, as protesters burned draft cards and U.S. flags, fought police in the streets, and bombed R.O.T.C. buildings. And for the oppressed, the experience of the war accelerated their understanding of colony and Empire.

From 1965 on U.S. imperialism jolted the Empire with the rapid escalation of its War. College students, feeling threatened by the draft, began holding mass Teach-Ins to debate Government policy. SDS (Students for a Democratic Society), which had been a small, social-democratic college group that was very anti-Marxist, began to take on a mass character and become more militant. One social scientist notes how dramatic the U.S. military build-up was: "In 1965, at the time of the first national Teach-In, the U.S. had approximately 30,000 troops stationed in that forlorn nation and a total casualty rate of 2,283 killed and injured. In 1967, by the time of the May anti-war rallies, we had approximately 375,000 troops under arms in Vietnam, a considerable number of additional troops in Thailand, and a total casualty rate of 60,000. And by 1969, two years later, the United States had approximately 500,000 troops under arms..."(1)

The Vietnam War posed a new crisis for the Black petty-bourgeoisie, many of whom were anticipating the fruits of Federal Civil Rights patronage. Traditionally the Black petty-bourgeoisie had welcomed the U.S. Empire's foreign wars. Wartime was viewed as an exceptional opportunity to "advance the race." During wartime the need for New Afrikan labour and men at arms gave the Black leadership a chance to demonstrate their useful loyalty to the Empire--and ask for concessions in return. W.E.B. DuBois and the NAACP supported the U.S. war effort during World War I (a position DuBois soon regretted). In World War II A. Philip Randolph, Paul Robeson, Adam Clayton Powell and the NAACP gave all-out support for the US conquests in Europe and Asia.

It was only in 1948, after waiting for integration and "equal opportunity" in the armed forces, that the Black petty-bourgeoisie began to balk at supporting the war machine. After a fruitless meeting with President Truman, A. Philip Randolph issued a call for New Afrikan college students to resist the draft. A League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation was formed: "I personally pledge myself to open counsel, aid, and abet youth, both white and colored, to quarantine any Jim Crow conscription system... I shall call upon all colored veterans to join this Civil Disobedience movement and to recruit their younger brothers in an organized refusal to register." Response was positive: polls in 1948 showed that 70% of New Afrikan college students favored the anti-draft campaign. Youth began refusing to register and refusing to serve in the Army.(2)

Randolph was hastily recalled to Washington, where a deal was struck to end the struggle before it could politically develop. President Truman signed the famous 1948 Executive Order No. 9981, ordering the military to practice "equality... without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin." The black petty-bourgeoisie had won their second major legal concession in this century from the Government. In return, Randolph had promised the imperialists that he would totally disband the League, suppress the talk that had already begun of forming a New Afrikan anti-imperialist movement, and isolate those New Afrikan anti-war resisters who had already gone to prison. The black petty-bourgeoisie protest leadership, having called their people into action as a bargaining chip for neo-colonial deals, once again abandoned their followers. From then through the Korean War in the 1950s and into the early Vietnam period, the Civil Rights leadership was a supporter of U.S. imperialism's far-flung military adventures.

At first the 1960s saw merely the continuation of this slavish practice. In July 1964 the mainstream Civil Rights leadership--SCLC's King, Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph, Whitney Young of the Urban League, and the NAACP's Roy Wilkins--issued a call for a halt on all New Afrikan demonstrations until the national elections were over in November.(3) President Johnson wanted to ensure settler votes by proving how his programs were controlling the New Afrikan movement. In December 1964, when Martin Luther King went to Sweden to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, he still refused to criticize U.S. foreign policy. When pressed by European reporters, King said he couldn't oppose U.S. military operations then going on in the Congo (Zaire) against the Patrice Lumumba government.(4) The position of the Black petty-bourgeoisie leadership in 1965-66 on the Vietnam War was clear. The Urban League, NAACP, the SCLC Board of Directors, National CORE, Rustin and Randolph, all went on record that New Afrikans should only concern themselves with Civil Rights issues. As King was to admit unhappily, his own class felt that a "Negro ought not speak out on such matters." Many of them, King remarked angrily, hoped to get ahead through the War.(5)

Anti-war sentiment was very strong, on the other hand, among New Afrikan youth, particularly on the streets. Nationalists had been denouncing the U.S. invasion since it began, and had been agitating for resistance to the imperialist draft. In 1964 Charles "Mao" Johnson, of the leaders of the UHURU nationalist formation in Detroit, sent a public statement of resistance to his draft board: "THERE AIN'T NO WAY IN HELL that I'm going out like a fool and fight my non-white Brothers in Asia, Africa and Latin America for 'White Devils'...I support everything you oppose and oppose everything you support."(6) Propaganda campaigns took place around the 1965 draft refusals of General Gordon Baker in Detroit and Ernie Allen in California. When boxing champion Muhammad Ali popularized resistance as well as the slogan "No Vietcong Ever Called Me Nigger," the New Afrikan opposition to the Vietnam War could not be hidden.

Anti-imperialist sentiment began breaking through the crust of the pro-government Civil Rights Movement in July 1965. Martin Luther King himself had been bothered about the moral inconsistency of urging pacifistic non-violence on New Afrikans while totally condoning napalming Vietnamese villages. He had been under heavy pressure from SCLC staff, his Euro-Amerikan socialist advisors, and even his father not to speak out. Finally at a rally in Petersburg, Virginia, King broke step with the rest of the mainstream leadership: "I'm going to sit by and see the war escalated without saying anything about it... The war in Vietnam must be stopped. There must be a negotiated settlement even with the Viet Cong." That act marked the beginning of King's divergence from the Government. At CORE's National Convention in Durham, N.C. the rank-and-file passed a resolution condemning the war. While CORE director James Farmer (and Marvin Rich, the Euro-Amerikan liberal who really ran National CORE) managed to get the motion rescinded, the sentiment of the membership was evident. And on July 28th, SNCC passed out an angry leaflet in McComb County, Mississippi over the death in Vietnam of McComb resident John D. Shaw - starting down the path already blazed by revolutionary nationalists.(7)

The U.S. Government tried to hold back the tide. All of a sudden Rev. King's telephone calls to the White House went unanswered. Word went out that Blacks who wanted Civil Rights reforms and patronage jobs should be loyal to the Johnson Administration. At the April 1965 SCLC Board of Directors meeting, the Board had voted that King could not criticize the war while speaking for SCLC.(8) In October of that year U.N. Undersecretary Ralph Bunche, the first Black to win a Nobel Peace Prize, said that if Martin Luther King refused to stop criticizing the War he "should positively and publicly give up" his leadership of the Civil Rights Movement. The Urban League's Whitney Young said at the White House that Blacks were "more concerned about the rat at night and the job in the morning" than about Vietnam. Even Bayard Rustin, Rev. King's long-time advisor and key strategist publicly argued that King was wrong. Anti-war politics were controversial in the middle-class New Afrikan community back then.(9)

When SNCC became the first Civil Rights organization to formally come out against the U.S. invasion, on January 6, 1966, it was greeted by "patriotic" hysteria from the Black Establishment. Political struggle intensified when Rev. King himself came out in support of Julian Bond, SNCC Communications Director, who had been barred from his seat in the Georgia State Legislature because of SNCC's stand. But the motion and sentiment of the New Afrikan masses was clear. SCLC's annual convention in April 1966 reversed the Board of Directors, endorsing Rev. King's anti-war position.

On April 15, 1967, Martin Luther King, together with Harry Belafonte, helped headline the massive 125,000-person Spring Mobilization anti-war march to the U.N. That march was coordinated by SCLC's James Bevel; 200 Euro-Amerikan draft resisters publicly burned their draft cards before Stokeley Carmichael took the microphone to accuse the U.S. of genocide in Vietnam.(10) Part of the Civil Rights Movement had broken with the Johnson Administration to re-join other liberal settler allies in the new anti-war movement. While the petty-bourgeois Civil Rights leaders who did break with the Government chose to express their anti-war position in one way, characteristic of their class, anti-war sentiment took a very different form among the New Afrikan masses.

.......

In the U.S. oppressor nation dissent over the Vietnam War finally grew to the point that it forces the Johnson Administration out of office in 1968, and certainly played a part in limiting imperialism's military options in Southeast Asia. Major contradictions came to light. Robert Williams had noted: "The American mind has been conditions to think of great calamities, wars and revolutionary upheavals as taking place on distant soil. Because of the vast upper and middle classes in the USA, that have grown accustomed to comfortable living, the nation is not prepared for massive violence... The soft society is highly susceptible to panic."(11)

Just at a time when Euro-Amerikan youth, with the security of the '60s boom years, were trying to reform settler society, the Government was ordering them to fight in a "dirty" war that was meaningless to them, in remote Asian jungles. To youth searching for justice, nothing seemed less just. The outrage sprang in part from their privileged lives, but was none the less socially explosive. 1965 saw 9,741 appeals of draft status to state appeals boards; 1966 saw 49,718 appeals; 1967 it jumped even higher to 119,167 appeals of draft status. Many thousands of youths were moving to Canada or becoming resisters, while millions were evading the draft on technicalities.(12)

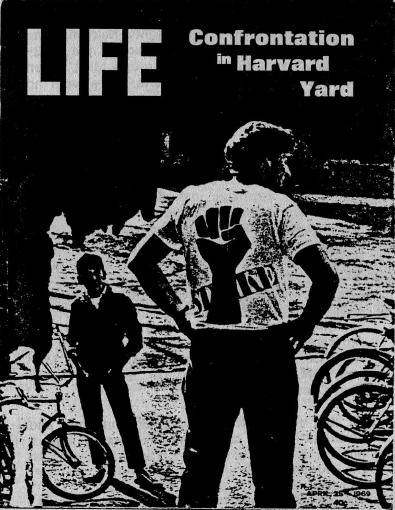

The anti-war movement was the "Civil Rights Movement" of settler college youth. It was their movement, using all that they'd learned from watching the Sit-Ins and the Civil Rights protests. White students gained the intoxicating feeling that what they did was world news, was making world history. Campuses became centers of feverish protest activity. The Vietnam War struggle was a framework that helped foster alternative culture, dissent in all ways from attitudes towards police to language to consumerism. Revelations over imperialism's immorality changed the way both Government and the major corporations were viewed. When the Harris Poll interviewed college students in June 1970, after Spring protests over Nixon's invasion of Cambodia, the social shock wave the '60s could be seen: 67% of the students advocated basic changes in "the system"; 11% said that they were "far left" (19% on the West Coast); 10% said that violence was the only way to change society.(13)

Imperialism's use of violence as an answer, particularly when settler college students themselves began getting beaten up and tear-gassed, gave legitimacy in their eyes to anti-Establishment violence. In particular, any form of disruption or illegal violence against property associated with the military or war industry was applauded. Anti-war ministers assured people that "human rights are more important than property rights." The role of political violence in the student movement was far greater than is now usually admitted. A history of the S.D.S. proves how true this was, and in particular outlines how the dimensions of anti-war violence reached a peak in May 1970, after Euro-Amerikan college students were shot gown at Kent State:

"In the spring of 1968, when bombs were first used by the white left, there were ten bombing instances on campuses; that fall, forty-one; the next spring, eighty-four on campus and ten more off campus; and in the 1969-1970 school year (September through May), by an extremely conservative estimate, there were no fewer than 174 major bombings and attempts on campus and at least seventy more off-campus incidents associated with the white left--a rate of roughly one a day. The targets, as always, were proprietary and symbolic: ROTC buildings (subjected to 197 acts of violence, from bombings to window breakings, including the destruction of at least nineteen buildings, all of which represented an eight-fold increase over 1968-69), government buildings (at least 232 bombings and attempts from January 1969 to June 1970, chiefly at Selective Service offices, induction centers, and federal office buildings), and corporate offices (now under fire for the first time, chiefly those clearly connected with American imperialism, such as the Bank of America, Chase Manhattan Bank, General Motors, IBM, Mobil, Standard Oil, and the United Fruit Company).

"But the violence wasn't all bombings and burnings. On the campuses this year there were more than 9,408 protest incidents, according to the American Council on Education, another increase over the year before, and they involved police and arrests of no fewer than 731 occasions, with damage to property at 410 demonstrations, and physical violence in 230 instances--sharp evidence that the ante of student protest was being upped. Major outbreaks of violence occurred in November in Washington, when 5,000 people charged the Justice Department and had to be dispelled by massive doses of CN gas (this was the demonstration which Attorney General Mitchell and Weather-leader Bill Ayers both agreed, in totally separate statements with totally different meanings, "looked like the Russian Revolution"); at Buffalo in March when police clashed with students and twelve students were shot and fifty-seven others injured; at Santa Barbara in February, when students kept up a four-day rampage against the university, the National Guard, local police, and the Bank of America, more than 150 people were arrested, two people were shot, and one student was killed; at Berkeley in April, when 4,000 people stormed the ROTC building, went up against the police, and kept up an hours-long assault with tear gas, bottles, rocks; at Harvard in April, when several thousand people took over Harvard Square, fought police, burned three police cars, trashed banks and local merchants; at Kansas in April, where students and street people caused $2 million wroth of damage during several nights of trashing and demonstrations, forcing the calling out of the National Guard; and finally the massive confrontation of May.

"...And for the first time in recent American history, actual guerrilla groups were established, operating in secrecy and for the most part underground, each dedicated to the revolution and each using violence means.

.......

"It is important to realize the full extent of the political violence of these years--especially so since the media tended to play up only the most spectacular instances, to treat them as isolated and essentially apolitical gestures, and to miss entirely the enormity of what was happening across the country. It is true that the bombings and burnings and violent demonstrations ultimately did not wreak serious damage upon the state, in spite of the various estimates which indicate that perhaps as much as $100 million was lost in the calendar years 1969 and 1970 in outright damages, time lost through building evacuations, and added expenses for police and National Guardsmen. It is also true that they did not create any significant terror or mass disaffiliation from the established system,... in part because Americans generally cannot conceive of violence as a political weapon and tend to dismiss actions outside the normal scope of present politics as so unnecessary and inexplicable as to seem almost lunatic. Nonetheless, the scope of this violence was quite extraordinary. It took place on a larger scale--in terms of the number of incidents, their geographical spread, and the damage caused--than anything seen before in this century. It was initiated by a sizable segment of the population--perhaps numbering close to a million, judging by those who counted themselves revolutionaries and those known to be known to be involved in such acts of public violence as rioting, trashing, assaults upon buildings, and confrontations with the police--and it was supported by maybe as much as a fifth of the population, or an additional 40 million people--judging by surveys of those who approve of violent means or justify it in certain circumstances. And, above all, violence was directed, in a consciously revolutionary process, against the state itself...

"The culmination of campus violence occurred in May, without doubt one of the most explosive periods in the nation's history and easily the most cataclysmic period in the history of higher education since the founding of the Republic.

"On April 30, Richard Nixon announced that American troops, in contravention of international law and the President's own stated policy, were in the process of invading Cambodia, and within the hour demonstrations began to be mounted on college campuses. Three days later a call for a national student strike was issued from a mas gathering at Yale, and in the next two days students at sixty institutions declared themselves on strike, with demonstrations, sometimes violent, on more than three dozen campuses. That was remarkable enough, especially for a weekend, but what happened the following day proved the real trigger.

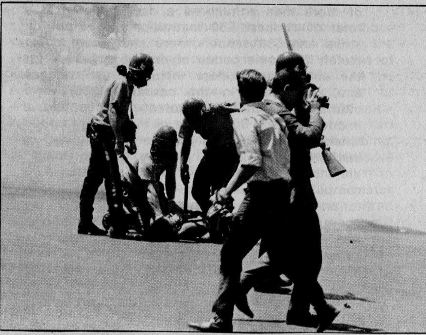

"On May 4, at twenty-five minutes after noon, twenty-eight members of a National Guard contingent at Kent State University, armed with rifles, pistols and a shotgun, without provocation or warning, fired sixty-one shots at random into a group of perhaps two hundred unarmed and defenseless students, part of a crowd protesting the war, ROTC, and the authoritarianism of the university, killing four instantly, the nearest of whom was a football field away, and wounding nine others, one of whom was paralyzed for life from the waist-down. It took only thirteen seconds, but that stark display of government repression sent shock waves reverberating through the country for days, and weeks, and months to come... The impact is only barely suggested by the statistics, but they are impressive enough. In the next four days, from May 5 to May 8, there were major campus demonstrations at the rate of more than a hundred a day, students at a total of at least 350 institutions went out on strike and 536 schools were shit down completely for some period of time, 51 of them for the entire year. More than half the colleges and universities in the country (1350) were ultimately touched by protest demonstrations, involving nearly 60 percent of the student population--some 4,350,000 people--in every kind of institution and in every state of the Union.* Violence demonstrations occurred on at least 73 campuses (that was only 4 percent of all institutions but included roughly a third of the country's largest and most prestigious schools), and at 26 schools the demonstrations were serious, prolonged, and marked by brutal clashes between students and police, with tear gas, broken windows, fires, clubbings, injuries and multiple arrests; altogether more than 1800 people were arrested between May 1 and May 15. The nation witnesses the spectacle of the government forces to occupy its own campuses with militia troops, bayonets at the ready and live ammunition in the breeches, to control the insurrection of its youth; the governors of Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and South Carolina declared all campuses in a state of emergency, and the National Guard was activated twenty-four times at 21 universities in sixteen states, the first time such a massive response had ever been used in a non-racial crisis. Capping all this, there were this month no fewer than 169 incidents of bombings and arson, 95 of them associated with college campuses and another 36 at government and corporate buildings, the most for any single month in all the time government records have been kept; in the first week of May, 30 ROTC buildings on college campuses were burned or bombed, at the rate of more than four every single day. And at the end of that first week, 100,000 people went to Washington for a demonstration that was apparently so frustrating in its avowed non-violence that many participants took to the streets after nightfall breaking windows, blocking traffic, overturning trash cans, and challenging the police.

"* Protests took place at institutions of every type, secular and religious, large and small, state and private, coeducational and single-sexed, old and new. Eight-nine percent of the very selective institutions were involved, 91 percent of the state universities, 96 percent of the top fifty most prestigious and renowned universities, and 97 percent of the private universities; but there were also demonstrations with a "significant impact" reported at 55 percent of the Catholic institutions, 52 percent of the Protestant-run schools, and 44 percent of the two-year colleges, all generally strict and conservative schools which had never before figured in student protest in any noticeable way. Full details can be found in a study by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, 'May 1970: the Campus Aftermath of Cambodia and Kent State.'"

.......

"...Despite Hoover's claim on November 19, 1970, that 'we have no special agents assigned to college campuses and have had none', documents liberated from the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, four months later indicate that every single college in the country was assigned an agent and most of them had elaborate informer systems as well. Even as tiny a bureau as the Media one engaged in full-time surveillance and information gathering on every campus its area, sixty-eight in all, ranging from Penn State with its thirty-three thousand students to places like the Moravian Theological Seminary with thirty-five students and the Evangelical Congregational School with forty-one, and it used as its regular campus informers such people as the vice-president, secretary to the registrar, and chief switchboard operator at Swarthmore, a monk at Villanova Monastery, campus police at Rutgers, the recorder at Bryn Mawr, and the chancellor at Maryland State College. As if that was not enough, the FBI added twelve hundred new agents in 1970, mostly for campus work, established a "New Left desk" (plus an internal information bulletin called, without irony, "New Left Notes"), and its agents were directed to step up campus operations..."

It is hard for those who didn't experience those years to grasp how the moral imperative of ending the War sanctioned anti-imperialist violence to millions of Euro-Amerikans. On the night of August 24, 1970 the Army Math Research Center at the University of Wisconsin at Madison was totally blown up by the anti-war student New Years Gang. Four years later Karl Armstrong was arrested in Canada for the bombing. At his Toronto extradition hearing, not only professors and businessmen and Vietnam vets turned out to testify for Armstrong, even former U.S. senator Ernest Gruening of Alaska. Gruening, who committed many colonial crimes in his own career, told the court: "We should have supported the Viet Cong and the NLF,...Resistance to this war is not only obligation but a solemn duty of the citizens of this country...All acts of resistance are fully justified, whatever form they may take."(15)

Karl Armstrong worked in the 1964 election campaign of Lyndon Johnson. But as he said, the War forced his personal evolution: "In the space of 2-3 years after 1966, I would get flashes of what was happening in Vietnam. At a certain point I really grasped what was going on there, and I wondered what had really happened to me, why I didn't feel that before. I began to really question my own values, my own humanity, what I had become to that point. The revelations in Indochina made me question everything in this country... I knew it was going to be a very destructive act. I thought that if the bombing of the AMRC would save the life of one Indochinese...to me that would be wroth it. Property doesn't mean anything next to life."(16)

The Vietnam War struggle awakened millions of settler youth to political activism and commitment, whether to electoral reform politics or to women's liberation or to socialism. The New Left was born out of this movement. Both armed revolutionary organizations and solidarity with national liberation movements, although numerically small trends, appeared for the first time in the U.S. oppressor nation history in the 1960s. The tragedy is that while there have always been individual Euro-Amerikan revolutionaries-and even small groups--that supported national liberation, the settler Left parties and trade unions had kept them ineffectually isolated and under control. Until the 1960s.

The New Left that grew out of the anti-war movement only laughed at such old-fashioned backwardness. They had been awed by the power of guerrilla war in Vietnam; impressed by the humanism and personal integrity of Che Guevara in a way that they never were by their own Government leaders. Heroic Vietnamese women were an example of women's liberation. By 1967 it was quite common for student activists to talk about armed revolution as the only way to "change the system," as the popularly vague expression went. This generation of settler radicals related to Third World revolutions as novices and students. This was a healthy corrective, necessary for the development of genuinely revolutionary Euro-Amerikan politics.

Revolutionary sentiments became so popular, although undeveloped, that even student leaders who were completely liberal in their outlook began to speak about armed struggle. In July 1967 Tom Hayden of the SDS declared : "Urban guerrillas are the only realistic alternative at this time to electoral politics or mass armed resistance." At the June 1967 SDS Convention at Ann Arbor, National Secretary Greg Calvert said: "We are working to build a guerilla force in an urban environment...Che sure lives in our hearts." Assistant National Secretary Dee Jacobson agreed: "We are getting ready for the revolution."(17)

SDS had grown to over 6,000 members (it was to grow much larger in the next year) and linked up anti-war activists on hundreds of campuses. While there was no political leadership, experience, party or strategy, there certainly was an unprecedented current of pro-revolutionary sentiment among Euro-Amerikan youth.

Within the broader Anti-War movement the idea of revolutionary solidarity, of internationalism, began to grow. When Walter Teague and the U.S. Committee to Aid the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam first began showing up at East Coast peace demonstrations with a large Vietnamese flag, they were called "crazies" by the liberal and pacifist leaders. At first, anti-war marches were supposed to be "American" and "patriotic," politely respectable dissent. The sight of fifteen or twenty youth with an "enemy" flag was shocking.

By early 1967, Teague had joined with John Gerassi, Frank Gillette and other New Yorkers to organize the Revolutionary Contingent. The RC tried to jack up the militancy of the giant April 15, 1967 anti-war march to the U.N. (the rally that both King and Carmichael spoke at). Their "contingent" raised the slogan "Support the Vietnamese Revolution" as opposed to the official march slogan of "Stop the War Now." Carrying Vietnamese and other national liberation banners, the small contingent broke away from the official march route to physically assault the Army recruiting booth in Times Square. The U.S. flag was burned. What was thought extreme in early 1967, a militancy few would take part in, was just foreshadowing what many thousands would be doing within a year.

Revolutionary Contingent's political program, which was heavily influenced by Guevarism, explicitly urged U.S. protesters to join guerrilla movements in the oppressed world:

"The revolutionary contingent is calling for two things from the dissenters all over the USA. One is the use of creative energy in designing and carrying-out dramatic, radical, peace demonstrations, which will be 'escalated'... Guerrilla action means fast, destructive actions, from which the perpetrators escape... This leads to the second call: for persons to join the struggle against U.S. imperialism in other countries. The Revolutionary Contingent has been in contact with representatives of the national liberation movements active on the American continent, and they have consented to call for citizens of the USA to join them (see Che Guevara's 'Message to the Tricontinental'); of course, only those with skills of use to guerrillas--medical and/or technical--and who are willing to fight are wanted... We can not longer talk--we must fight!"(18)

Obvious problems existed with the RC, from police agent provocateurs using "militant" actions to start fights with other anti-war activists to the RC's inability to work within the broader anti-war movement. And on a larger scale, a program that had no revolutionary answers for here ("The purpose of the Revolutionary Contingent is to enable those American radicals who have found the struggle in the United States itself useless at this time, to go abroad and fight in liberation movements in other countries.") could not play a role in all the new political forces being born in the U.S. oppressor nation. But like other young collectives and revolutionary groupings at that moment, the short-lived RC manifested the new trend of anti-imperialist internationalism.

.......

For New Afrikans opposition to the War was not a separate struggle; it enriched their own liberation movement. Some organizations, such as SNCC and SCLC, united with the activities of the Euro-Amerikan anti-war movement. Others such as National Black Draft Counselors worked to build resistance in their own communities. On the mass level, the simmering rebellion among New Afrikan GIs did much more than just protest the war, it played a large part in ending it.

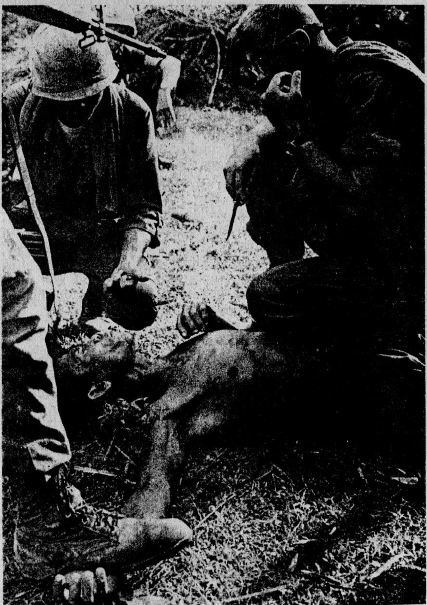

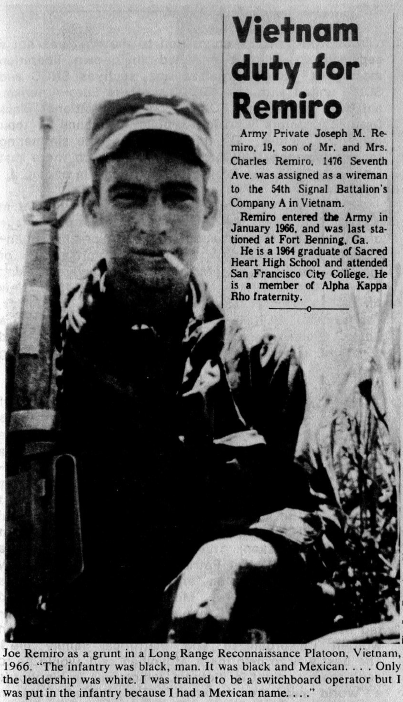

As everyone knows, New Afrikans were present in the U.S. forces in Vietnam far above their percentage of the U.S. Empire population. Colonial cannon-fodder, New Afrikans would often comprise 50% or more of the actual infantry platoons that were seeking out the Vietnamese liberation forces. In 1970, New Afrikans accounted for 22% of the U.S. casualties. This was no accident. One soldier, Ron Brown, told a Boston Globe reporter: "In my mind Vietnam has killed a lot of young blacks in this country, eliminating them, as if the war was a plan to do so."

While New Afrikan youth had far less chance of escaping the draft than Euro-Amerikans, there was also a conscious imperialist program to pacify the ghetto by draining off street youth to 'Nam. The idea was to take unemployed young men--who were identified as the main force in ghetto "riots"--into the Army regardless of supposed literacy, medical or arrest standards. This program, started in 1966, was called "Project 100,000" (although in the end many times that number were taken). It was the brainchild of White House advisor Daniel Patrick Moynihan. he cleverly put it forward not as an "anti-riot" program, but as a social welfare measure. Moynihan had hypothesized that these unemployed men were allegedly maladjusted because they had been dominated by New Afrikan women ("disorganized and matri-focal family life"). The Best way to help them, Moynihan said, would be to send them to fight in Vietnam, which was in his words "a world away from women." Col. William Cole, in command of the Army's 6th Recruiting District in San Francisco, was more to the point when he said: "President Johnson wanted those guys off the street."(20) The Vietnam free-fire zone was to be a pacification program for New Afrikans as well as Asians--or as many said, "using the nigger against the gook."

President Johnson's plan backfired on U.S. imperialism, spreading the Black Revolution to Army bases and Navy carriers around the world. And in Vietnam, to be sure. That there was heavy white supremacy in the imperialist military needs no explaining. New Afrikan resistance took many forms. In August 1968, elements of the 1st and 2nd Armored Divisions at Fort Hood, Texas went on alert for possible "riot control duty" (counter-insurgency) in Chicago. The White House was worried that anti-war protests at the Democratic Party Convention might also trigger mass rebellion in the ghetto. After several hundred New Afrikan G.I.s gathered at a spontaneous base protest rally that night, saying that they would not bear arms against their own people, fourth-three were arrested and court martialed (the "Ft. Hood 43").

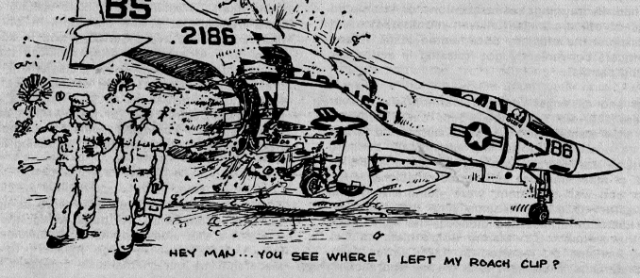

These protests and embryonic organization took place throughout the imperialist military. 139 New Afrikans, half of who were women, were arrested after demonstrations at Ft. McClellan, Alabama in November 1971. In West Germany, Gen. Michael Davidson of the U.S. 7th Army admitted that "Black dissident organizations could turn out 1500 soldiers for a demonstration." He admitted it because they were in fact doing it. In the Navy, shipboard rebellions, in which New Afrikans were joined by small numbers of anti-racist Euro-Amerikan sailors, became common. Self-defense actions against oppressive officers and seamen led to outbreaks of mass fighting. On the aircraft carrier U.S. Kitty Hawk the mass fighting on October 11, 1972 lasted for 15 hours, ending up with the hospitalization of forty settler officers and men. On the carrier U.S. Constellation, New Afrikan self-defense struggles forced the captain to cancel a 1972 training cruise and race for port to get police reinforcements.(21)

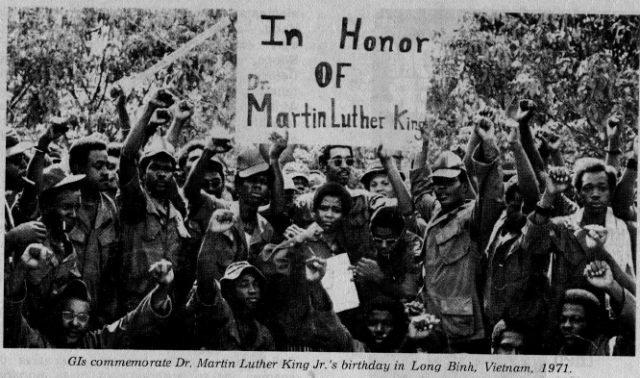

The spearhead of the struggles--which were not "anti-war" struggles in the narrow sense, but anti-oppressor nation struggles--took place in 'Nam, where the war brought everything to a head. Under intense danger and oppression, New Afrikan GIs began to focus their energy on their common identity and resisting the settler military. Afro hairstyles, Afrikan jewelry, music, political study, and setting up their own territory were universal. Sabotage by noncompliance was widespread.

A report on the Vietnam base situation by the 1970s from the Lawyers Military Defense Committee stated: "Thus, the power gained by Blacks was subtle. They simply did not go along with the program, go to the field, or, in many units, work. The cost of this was that about 10 percent of their number would be in jail, under charges or pending administrative discharge, at any one time. As one Black said: 'If I don't go to the field, what are they going to do? Put me in jail?' Laughter followed." One out of every ten New Afrikan G.I.s in 'Nam was in jail or on charges on any given day. Sixty percent of the prisoners at the main stockade at Long Binh (known everywhere as "the LBJ"--Long Binh Jail) were New Afrikans. Almost all the maximum security prisoners were there for being "militants," New Afrikan or other Third World. Small wonder that when New Afrikan GIs at the Long Binh base commemorated Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s birthday in 1971 with a march, the column was headed by the liberation flag and the GIs chanted: "Free the brothers in LBJ!" and "Free Angela Davis!"(22) The New Afrikan Revolution was starting to take place in 'Nam.

The level of armed resistance with settlers was high and reaching the take-off point. Fistfights, shootings and armed stand-offs between New Afrikan GIs and white supremacists were common, at times immobilizing major Army bases (such as Danang in early 1971). Individual incidents fall into familiar patterns. One night in January 1971 two settler majors, returning from drinking at the officers club, passed a hootch where loud soul music was being played. The two majors went in and ordered the brothers to turn it off, yanking the electric cord out when the men refused. In the ensuing argument both settler officers were shot to death. One soldier, Alfred "Brother Slim" Flint, was sentenced to 30 years at hard labor.

The same month conditions reached an intolerable level at a small fire base outside Khe Sanh, due to a white supremacist lieutenant and sergeant leading their settler GIs in an upfront manner: the Confederate flag flew over the fire base, and New Afrikans were openly called "nigras." When a New Afrikan GI tried to explain why New Afrikans were refusing to go out on patrol under those circumstances, the John Wayne-ish officer grabbed for his .45 pistol. Pvt. James "Brother Smiley" Moyler was then forced to blow him away with his M-16.

Assassinations of officers was a rapidly growing phenomenon, particularly since many settler GIs also found it necessary to eliminate or intimidate piggish officers. Fraggings--the anonymous grenade rolled into an officer's tent or room as he slept--became a permanent part of 'Nam folklore. The Lawyers Committee said: "Fraggings became so common that the 'lifers' (career military men, usually officers and noncoms--ed.) were in perpetual fear of their men. (Fragging was not an all-Black phenomenon, though.) One company commander told an LMDC lawyer that he jumped every time he heard a clap of thunder. Officers and NCO's played what was called 'musical beds'--they moved every night. Some commanders would take an enlisted 'hostage' to sleep in their hootches at night."(23) In 1969 there were 96 officially documented fraggings in units in Vietnam. That number jumped to 209 in 1970, and then jumped again to 154 for just the first six months of 1971. One Army brigade had 45 fraggings, assassinations or attempted shootings of officers in just eleven months.(24) And these were just the officially documented cases. Many settler officers conveniently got "missing in action" or died during patrols.

Nixon and Kissinger, die hard warmongers if ever there were any, didn't pull the troops out of Vietnam because they wanted to. U.S. imperialism was forced to pull its occupation force out of Vietnam because the military was literally starting to come apart, at the bring of mass mutinies and armed rebellions. Drug use and anti-war sentiment were demoralizing and eroding settler G.I.s at the same time that the Vietnamese liberation armies had blocked "the light at the end of the tunnel." U.S. Marine Corps historian Col. Robert D. Heinl, Dr. reported in 1971: "...our Army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers...dispirited where not near mutinous."(25)

Imperialism was losing control of its own military, which was potentially a much bigger crisis than Indochina itself. Washington officials visiting Army bases were freaked out at the development of "Black militant" culture--in West Germany and in some units in 'Nam, New Afrikans had often replaced regulation salute with the "Power" sign (raised fist). Astonished brass would watch as local settler officers would be forced to return salutes to the New Afrikans giving them the "Power" sign. Fear of New Afrikan mutinies was ever-present in command levels. Nixon had to get the troops out of Vietnam quick or risk losing his army.

.......

The anti-war struggles also serve us as a textbook on internationalism. To begin with, internationalism was not a one-sided, spontaneous development in the U.S., but was due in large measure to the correct leadership of our Vietnamese comrades. For many years they had studied U.S. political affairs, and had carefully planned and organized ties with progressive-minded Amerikans. Conferences abroad to deepen personal ties with anti-war activists, special literature, coordination between the U.S. anti-war leadership and their own political offensives, all characterized the detailed work Vietnamese comrades put into the development of close relations.

Secondly, U.S. solidarity was never seen by the Vietnamese as a substitute for for educating and mobilizing their own people to military victory. Even at the height of the U.S. anti-war storm, the Vietnamese comrades never even suggested that liberation would come any other way than through Peoples War. It was their own strategic understanding of self-reliance as primary that became the foundation for successful internationalism. International solidarity not only requires correct leadership, but cannot be a substitute for self-reliance on both sides. This is in distinct contrast to the prevailing attitude within the U.S. Empire now.

International solidarity was built by the Vietnamese on a principled basis. They never intervened within U.S. movements, despite their considerable prestige, to boost some factions or leaders as opposed to others. Neither did they ever countenance the slightest suggestion that their foreign friends could determine the policies of the Vietnamese liberation struggle.

During the complex course of the war, at several points organizations influenced by Trotskyism attempted to put themselves forward as more advanced than the Vietnamese Communist Party on how Vietnam's liberation struggle should be conducted. Around the Paris Peace Accords, for example, groups such as the Socialist Workers Party and the Progressive Labor party accused the Vietnamese comrades of "selling out" to U.S. imperialism. The Vietnamese sharply reproved such positions (which in any case were soon to be proved to be confused at best) while stressing as still primary their Revolution and progressive-minded peoples within the Empire.

The Vietnamese consciously developed alliances with a broad spectrum of Euro-Amerikans--from religious peace leaders like Rev. A.J. Muste to the Weatherman-SDS to liberal opportunists such as Ramsay Clark and Tom Hayden. These relationships were built on two levels: on a primary level they tried to make common cause with everyone who recognized their national sovereignty and the justice of their liberation struggle. This included the large and respectable National Mobilization Committee as well as the small, widely-disliked Workers World Party. On a broader level the Vietnamese tried to encourage every constructive contradiction around the War within U.S. society. Every proponent of either negotiations or U.S. troop withdrawal was encouraged. Even though the Vietnamese knew that U.S. Senator George McGovern was no more their friend than Lyndon Johnson or Richard Nixon, they publicly encouraged his 1968 Presidential campaign in order to further the disunity within the imperialist camp. In no case did the Vietnamese narrow or limit their international alliances to suit the desires of one or another ally. No one was the "chosen" ally or owned the Vietnamese solidarity "franchise."

Within the U.S. Anti-War movement the rapid progress of internationalism was, of course, also uneven and with its own contradictions. Euro-Amerikan anti-war activists tended to view the anti-war struggle as theirs, as wholly Euro-Amerikan. And today, in the 1980s, the imperialists and their media tend to portray the settler anti-war movement as the decisive factor in the U.S. defeat. While the opposition to the war within White Amerika was massive, its point of unity was opposition to the "senseless" of U.S. troops. Most settlers who opposed the War on that basis were politically pro-imperialist overall.

So after the Nixon Administration was forced to withdraw U.S. troops in 1971-1972, organized settler opposition to the War totally collapsed seemingly overnight. Some of the anti-war radical bombing was done out of a disbelief that the movement could end the War. Which was in fact true. The New Afrikan Revolution, as we have seen, continued to play a much more important role in destroying the U.S. war effort than the Euro-Amerikan peace activists have ever understood.

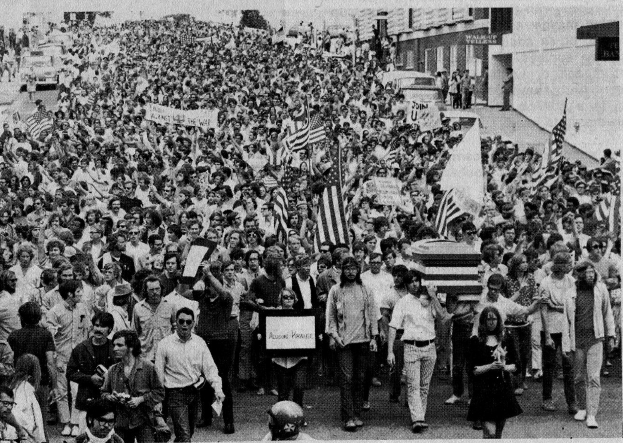

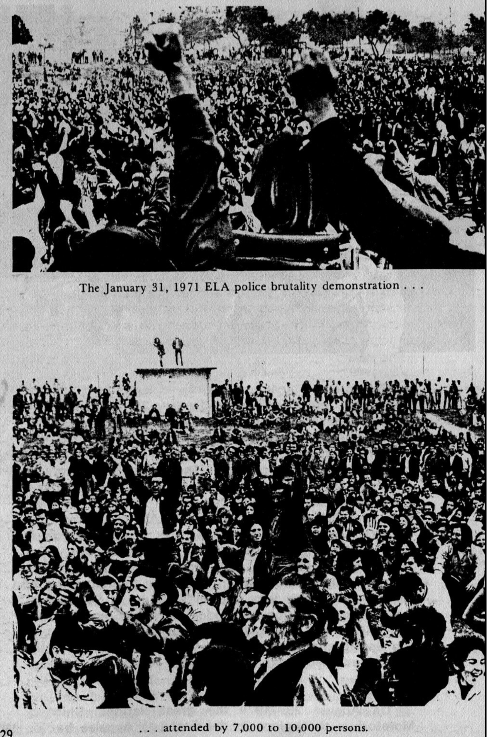

The mass Chicano Moratorium Movement in the Southwest, which led to the January 31, 1971 East Los Angeles Massacre in which sheriff's deputies shot down 35 unarmed Chicano demonstrators, showed how the solidarity between two national liberation movements had a special significance. The Chicano Moratorium began in 1970, grew just as the white Anti-War movement was declining, and became a rallying point to unite the Chicano Movement. The chairperson of the Chicano Moratorium Committee was Rosalio Munoz, a draft resister and former UCLA student leader. On February 28, 1970, the new Moratorium group in Los Angeles held a 6,000 person march in pouring rain. A film of the march was shown around the Southwest, leading to a decision to hold a National Chicano anti-war rally in Los Angeles at the end of the Summer. In the Spring and Summer there were local Chicano anti-war demonstrations all over Colorado, Texas, California.

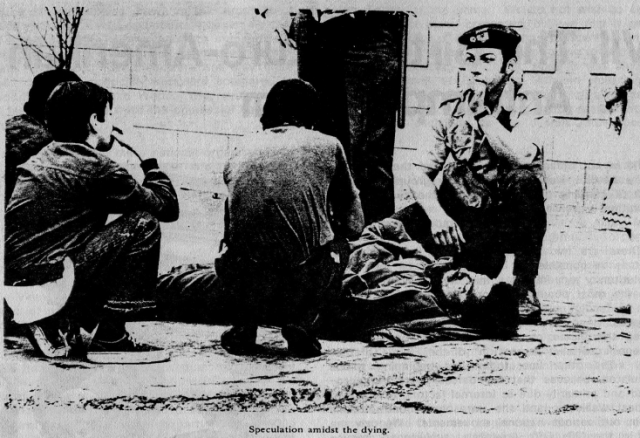

On August 29, 1970 the great National Chicano Moratorium took place in the East Los Angeles barrio. 20,000 Chicanos, together with Asian, Indian, New Afrikan, Puerto Rican and Euro-Amerikan allies, marched down Whittler Boulevard to Laguna Park. Many thousands lined the streets, cheering and joining in. Families with children came to the Laguna Park rally. Wedding parties joined the march, with bridal gowns and tuxedos and all. it was a festive day. The Moratorium was far more than an anti-war action. It was a mass statement against oppression, in which anti-imperialist slogans and consciousness were very evident. Using the pretext of a disturbance at a nearby liquor store, sheriff's deputies and riot police began moving against the rally, driving the thousands out of the park with tear gas, clubs and bullets. The crowds resisted the police and there were fistfights, barrages of bottles, and police cars torched. Afterwards Laguna Park was littered with lost shoes and lost children. Three people were killed. One, KMEX News director Ruben Salazar, was shot by the police in the Silver Dollar Cafe, where he had stopped after the melee. Salazar was the most vocal critic in the Los Angeles media of police brutality. That night there were "riots" and burning of stores in the barrios in the area. Four policemen were shot.

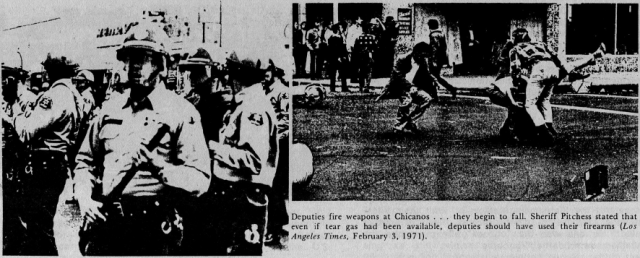

After that anti-police violence spontaneously erupted at barrio marches and demonstrations. The customary community parade on Mexican Independence Day, September 16th, ended in mass fighting between rock-throwing youths and the police. Chants of "Chicano Power" and "Raza si, guerra no" against the Vietnam War, grew during the parade. At the parade's end, fighting began. 64 deputies and police were injured, one deputy and two Chicanos wounded by gunfire. On January 9, 1971, the Moratorium brought 1000 demonstrators to a rally against police brutality in front of the L.A. police headquarters. Again fighting broke out. Finally, on January 31, 1971, the Moratorium held a rally of 10,000 Chicanos. Afterwards a thousand Chicano youth attacked the sheriff's police station, setting it afire. As the militant crowd attempted to move up Whittier Boulevard, the deputies opened fire. Suddenly people were falling. At least 35 Chicanos were shot (some with lighter wounds stayed away from hospitals and police), one of whom died. 22 more than were shot at Kent State.(26)

Footnotes

(1). IRVING LOUIS HOROWITZ, The Struggle Is The Message: Organization and Ideology of the Anti-War Movement, Berkeley, 1970, p. 105.

(2). DANIEL S. DAVIS, Mr. Black Labor, N.Y., 1972, p. 126-130.

(3). LEWIS, p. 249-250.

(4). Ibid., p. 260.

(5). Ibid., p. 304-305.

(6). COMMITTEE ON UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES, U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, Guerrilla Warfare Advocates in the United States, Washington, 1968, p. 17-18.

(7). LEWIS, p. 303; ROBERT W. MULLEN, Blacks in America’s Wars, N.Y., 1973, p. 68.

(8). LEWIS, p. 296.

(9). Ibid., p. 312 and 357.

(10). Ibid., p. 311 and 304.

(11). HOUSE COMMITTEE, op. cit., p. 21.

(12). HOROWITZ, p. 15.

(13). NEIL MILLER, “Coming of Age in the ‘80s”, In These Times, Oct. 17-23, 1984.

(14). KIRKPATRICK SALE, SDS, N.Y., 1973, p. 632-643.

(15). DAVID SIFF, “Judgement At Madison”, University Review, March, 1974.

(16). Ibid.

(17). HOUSE COMMITTEE, op. cit., p. 40-46.

(18). Ibid.

(19). MULLEN. p. 77-79.

(20). MYRA MACPHERSON, Long Time Passing: Vietnam and the Haunted Generation, Garden City, 1984, p. 552-571.

(21). MULLEN, p. 81-84.

(22). DAVID F. ADDLESTONE & SUSAN SHERER, “Race in Viet Nam”, Civil Liberties, February, 1973.

(23). Ibid.

(24). MACPHERSON, op. cit.

(25). FRED HALSTEAD, Out Now!, N.Y., 1978, p. 637.

(26). DR. ARMANDO MORALES, ANDO SAGRANDO, I Am Bleeding, La Puente, 1972, p. 570-575.