“It is not defeatist to acknowledge that we have lost a battle. How else can we ‘regroup’ and even think of carrying on the fight? At the center of the revolution is realism.”

-- Comrade George Jackson

There are two opposing political lines today on what is responsible for the setback of the 1960s revolutionary movements within the U.S. Empire. One line, the most popular and prevailing opinion, doesn’t wish to recognize that the ‘60s movements were truly defeated. And to the extent that it admits this fact places the blame on external factors, primarily the “savage imperialist repression” of the FBI’s COINTELPRO. The other line, today just beginning to be articulated, believes that the defeats were very profound and primarily due to internal factors, to our own political weakness and the unresolved contradictions within our various national movements. We can see this in the ‘60s Euro-Amerikan revolutionary movement, a movement which suffered defeat despite the fact that it wasn’t even scratched by imperialist repression.

The U.S. oppressor nation revolutionary movement that began forming in the late 1960s in and around SDS (the college Students for a Democratic Society) had a definite class character and a definite political program. Its ranks were composed of petty-bourgeois youth, with a leadership that tended to come from elite universities and from the most privileged classes and strata. Its program was and still is centered on solidarity work with the national liberation movements. With no proletarian class in its own society, that young movement was drawn to the struggles of oppressed nations. It was an important beginning that for the first time white people were not automatically seen as the center of everything, that young Euro-Amerikans understood that they were not only more privileged, but were politically backward compared to the revolutions of the Third World. The revolutionary idea of taking leadership from the oppressed began to take root.

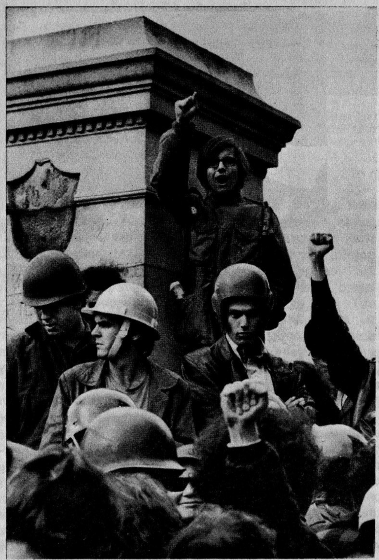

In late 1969 SDS, the mass national organization of student radicalism and protest, split into two political tendencies. The first was the Anti-Imperialist tendency, most visibly led by the Weather Underground Organization. Many of their leading personalities had been among the most-publicized student radicals. They viewed the struggle as primarily an anti-imperialist one, and advocated armed propaganda actions to spark off the spontaneous cultural/political uprising of settler youth. Comradely ties were established with both the Vietnamese and Cubans. The second, opposing school of thought was the “Marxist-Leninist party-building” tendency, initially led by the Progressive Labor Party’s “Worker-Student Alliance” and the Revolutionary Youth Movement 2 student bloc (whose elements became the October League, Revolutionary Communist Party, etc.). This tendency viewed the struggle as a classic, European-style worker vs. capitalist workplace conflict and advocated using trade union reform campaigns to build a party like the 1930s Old Left. China was seen as the only world vanguard by them. And so some thousands of radical settler youth began the search for revolutionary answers to the future of the U.S. Empire.

Fifteen years of practice have brought both tendencies to defeat. Their common situation is that neither tendency was able to put its program into successful practice, although initially each was leading thousands of activists and supporters. The “M-L party-building” tendency was never able to build a party and has no following among white workers. The Anti-Imperialist tendency does not lead any mass struggle against U.S. imperialism, and has never been able to build either an army or revolutionary organization worthy of the name. We do not wish to belittle the efforts of many comrades, but we find it necessary—a question of life and death—to now be painstaking about what is real. We are not going to discuss the “M-L Party-Building” tendency, since it was always a rightward trend of Bourgeois Marxism imitating the old CPUSA. To us the development of revolutionary forces within the U.S. oppressor nation rested with the efforts and decisions of the overall Anti-Imperialist tendency.

The new Anti-Imperialist tendency that had come together in 1968-70 out of the student anti-war movement was on an organizational level both large and decentralized, without any overall coordination of organization. Its people were active on many fronts, in university anti-war groups, community organizing projects, local defense committees for the Black Panthers or other Third World militants, prison support groups, small clandestine collectives or other embryonic revolutionary groupings (actually, many were in two, three or all of the above simultaneously or in quick serial order). While the Weather Underground (WUO) was doubtlessly the most publicized organization of this tendency, it actually had organized and directly led only a small percentage of the whole political current.

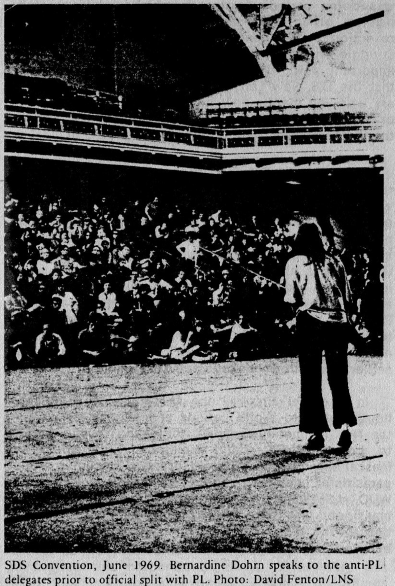

On the political level, the Anti-Imperialist tendency struggled from the beginning with a major contradiction around its settlerism. That it even had this struggle was important progress. And uneven political development was inevitable for a brand-new revolutionary movement—the first ever in its nation. It was also true that this was a student leadership, created in a few short years on college campuses. When they had to confront the larger society—the “real world”—the Anti-Imperialist leadership had little idea of what to do. The principal problem was that even those Euro-Amerikans who looked to the national liberation wars as the vanguard, who viewed themselves as following the Vietnamese, Mao and Che, and the New Afrikan Liberation Movement, did so in a settleristic way. That is, the new settler revolutionaries were relying on the oppressed nations—New Afrikans in particular—to solve their problems for them. Privilege and parasitism, the hallmarks of White Amerika, extended even to revolution, which the revolutionary settler elite would supposedly get simply by sticking close to the Third World struggles. “Hitching a ride on the BLM.” Or as Bernardine Dohrn exclaimed: “There’s going to be a revolution, and Blacks are going to lead it.” That was a very popular concept then among U.S. revolutionaries as a whole (encouraged by the Black Panthers, SNCC, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and others).

The movement’s inability to overcome its settlerism was decisive in the end. This can be seen, for example, in the development of two different organizations, in opposing wings of the Anti-Imperialist tendency and with different history, program and tactics. Despite the real political contributions of both, they were at first crippled and then led into defeat by their settleristic thinking.

LSM AND WUO

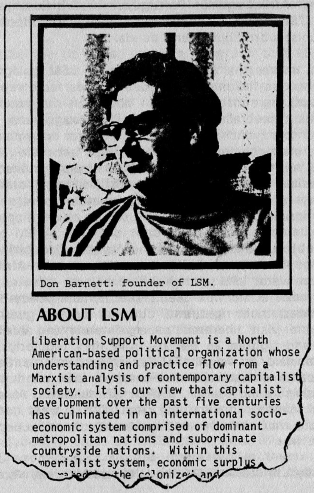

The Canadian-based LSM (Liberation Support Movement) was best-known for its pioneering role in Afrikan liberation support work. It was a relatively small staff organization, with educational centers in British Columbia, the Bay Area, Seattle, and New York City, rather than a mass membership organization. Its founder and chairperson was Don Barnett. A radical anthropologist, Barnett had spent years working in Afrika and had developed relationships with many revolutionaries there. His books Mau Mau From Within and The Revolution in Angola: MPLA became basic reference works on Afrikan liberation. LSM actually started as the “African Support Committee” in the late 1960s, at a time when few here knew who Amilcar Cabral or Agostinho Neto were—or even where Mozambique was on the map!

LSM’s political line was a radical departure from the customary perspectives of the settler left. It correctly opposed Euro-centrism, of seeing Europe and the U.S. as the center of political events. And LSM faced the fact that the level of imperialist social bribery was so high here that the Euro-Amerikan masses were pro-imperialist. Their conclusion was to make proletarian internationalism a reality by merging with the vanguards in the Third World: “...we in LSM view the revolutions of the countryside as the vanguard forces of a single revolutionary process... The central component of our strategy has been the development of proletarian internationalist links with national liberation movements.”(1)

Don Barnett, in laying out LSM’s program, saw himself and his comrades as full participants in the revolutions of the Third World. While he recognized the important difference between oppressor (“city”) and oppressed (“countryside”) nations economically, Barnett’s version of internationalism wiped out these distinctions in politics. LSM’s undeveloped internationalism didn’t really grasp the right of self-determination of oppressed nations or the reality of nations and national differences at this stage of history:

“...l would suggest that what we need is a dual ‘urban-rural’ strategy. On the ‘rural’ or neo-colonial front this will involve United States revolutionaries, together with militants of other metropolitan centers, in both direct and indirect participation in revolutionary anti-imperialist struggles... there are literally thousands of young militants in the capitalist centers who would be willing to serve in the anti-imperialist struggles in the imperial ‘countryside’... In fact, as the revolution spreads to increasing numbers of colonies and neo-colonies within the United States-dominated international capitalist system, the whole notion and reality of exclusive ‘national’ boundaries may begin to fade into relative insignificance. It is surely time for the United States Left to realize—and act accordingly—that there will not be an isolated ‘American’ revolution.”(2)

Although LSM in 1968 pictured a future in which many thousands of Euro-Amerikan, French, German, Japanese and other oppressor nation youth would play a significant role in the revolutions of Afrika, the reality was quite different. LSM did accomplish a number of positive things. While some cadre like Carroll Ishee (who recently died in combat with rebel forces in El Salvador) patiently sought technical education so that they could usefully participate in a liberation army, LSM’s real work was as a basic U.S.- Canadian support group. Funds were raised, medical supplies sent, literature printed, speaking tours sponsored. The first North Amerikan lecture tour by an MPLA representative was arranged by LSM in 1970. In 1975 LSM bought and set up a print shop for MPLA in Angola. LSM literature and slideshows were the main sources of information here for some time on the movements in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and Zimbabwe. At a time when attention was focused on Southeast Asia or Latin Amerika, LSM’s educational work about Afrika was an important contribution.

The central error lay in these Euro-Amerikans and Europeans falsely assigning their work a revolutionary status, and falsely locating their work as within the movements of other nations. In LSM’s subjective thinking the Afrikan guerrillas fighting in the forests and the Euro-Amerikans operating a printing press in Oakland, California were both parts of the same revolutionary movement. Showing a slideshow about Afrikan revolution was made equal to actually doing the Afrikan revolution. In reality, LSM was strictly an organization of those who sympathized with and supported the revolutions of others—and by this we mean other nations. Not content with this modest contribution to internationalism, LSM tried to blow its significance up into a whole different thing. There is an old saying that “the road to Hell is paved with good intentions.” In this case solidarity and good intentions became a cover for advancing the parasitism so deeply rooted in settler culture.

What is key here is not whether one is showing a slide show or shooting a rifle (although that too is an issue), but whether people take up their true political responsibilities as revolutionaries. LSM refused to deal with the complex problems and duties of making revolution in the U.S. oppressor nation by pretending to themselves that they were too busy making long- distance revolution for Angola and Mozambique. While this is an example of petty-bourgeois subjectivism in political strategy, LSM was only more open and above-board than others in how they viewed matters. It is common in the U.S. Left for “revolutionaries” to think that supporting the revolutions of others is all that is required. Revolution is reduced to a spectator sport.

LSM’s unwillingness to confront their own reality as European settlers, as privileged citizens of the settler Empire, inevitably left them open first to subjectivism and then to negating their original anti- imperialist intentions. LSM shied away from directly supporting in deeds those who were fighting “their” Empire, such as the B.L.A. or A.I.M. or the F.A.L.N. This is the first duty of any oppressor nation communist as we know, Conveniently, it was thought more important to directly support those who were fighting in far-off Afrika against Portuguese or British imperialism. “Solidarity” became a cover for its opposite. Communist words but liberal deeds.

Even more, the Euro-Amerikans in LSM assigned themselves as the main comrades (and de facto representatives) here of the Afrikan liberation movements. This meant several things. First LSM exaggerated its potential role (which was very limited) and downplayed the historic relationship between New Afrikans and the continental Afrikan struggle. Insofar as possible, LSM tried to keep Afrikan liberation solidarity a “white” issue under settler control (a familiar story to be sure).

Then too, LSM’s aid was not of the “no strings” variety. As supposed equal participants in Afrikan liberation wars, LSM demanded that it be allowed to inspect how its aid was used. That is, LSM policy held that it was their right and duty to inspect guerrilla bases and visit liberated zones, interviewing Afrikan cadres and fighters in depth. And they regularly did so, particularly in Angola. This arrogant interventionism became characteristic. For years LSM conducted a running feud with ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union), maintaining that ZANU was not a legitimate liberation party and wasn’t conducting a guerrilla war.

Finally, in 1974 LSM had to admit that “today ZANU is carrying the major burden of armed struggle in Zimbabwe,” and tried to establish friendly relations with ZANU; LSM continued criticizing ZANU for not letting LSM observers into their guerrilla camps and into their rural underground. LSM News not only still said in print about ZANU that “we have to remain somewhat sceptical regarding their claims to ‘liberated’ areas and population,” but said that “ZANU claims” could be “substantiated” by LSM observers. Why should a liberation army of 20,000 fighters, with popular bases of support, need validation by visitors from an oppressor nation? This is the kind of “equality” that colonial missionaries or intelligence agents aspire to. It should be no surprise that by 1975 many people, including some Afrikan revolutionaries, questioned if LSM had been infiltrated or taken over by the CIA as an intelligence-gathering project.(3)

Like the tip of an iceberg, to grasp that LSM was practicing false internationalism only leads us deeper. After all, it takes two sides to make a relationship. Why did some national liberation parties go along with and encourage LSM? There is no doubt that LSM consciously or unconsciously targeted its efforts on less politically developed and more internally divided liberation movements. LSM would never have been able to practice its arrogant interventionism on the Vietnamese communists, for example. LSM’s strongest connection was to the Angolan struggle and specifically to MPLA, but at a time not so coincidentally when the Angolan liberation movement was divided into three warring parties and MPLA itself was split into three openly hostile factions (complete with assassination attempts and coups). There was a strong neo-colonial current there. Confused and opportunistic alliances are rarely one-way streets.

LSM’s false internationalism led it into a blind alley. As the Afrikan liberation movements—once almost unknown here—got close to seizing state power, they became very attractive to liberal imperialism. Church groups, liberal foundations, international bodies such as UNESCO, Oxfam, World Council of Churches, etc. all got interested in them. Other (and larger) settler left groups suddenly discovered where Guinea-Bissau, Angola, Mozambique and Zimbabwe were on the map, and got involved in solidarity activity. LSM rapidly became a smaller and smaller factor in the overall aid situation. In May 1974, MPLA President Neto led a delegation on a Canadian solidarity tour. But the tour was sponsored indirectly by the Canadian Government, and LSM was cut out. What really said it to LSM was that MPLA didn’t even bother to tell them about the tour.(4) LSM’s opportunistic program met its end when its former allies found bigger opportunities elsewhere. The chickens always do come home to roost. Increasingly unimportant and cut off from Afrika, with a program that plainly didn’t work, LSM went out of existence.

While LSM bears responsibility for its own politics, it is important to see their problems as general within the Euro-Amerikan New Left and not completely unique. Intervening in the affairs of oppressed nations is an old liberal settler habit. Trying to get over on revolution by fastening yourself parasitically to one or another national liberation movement became popular in the ‘60s. LSM was just more politically explicit, a clearer example. Again, the LSM cadre began with revolutionary intent and concern for meeting internationalist obligations. And their effort led to real contributions. But when petty-bourgeois settlerism prevailed and finally became primary, LSM’s positive aspects were negated and could not be used toward building a new revolutionary movement.

.......

The Weather Underground (WUO) was at the other end of the Anti-Imperialist tendency from LSM. While LSM’s program called for joining the revolution taking place in the Afrikan “countryside,” WUO called on settler youth to make revolution in the “city” of the U.S. metropolis. Instead of just supporting revolutionary guerrillas in other countries, WUO called on settler youth to be guerrillas in their nation. While other organizations of the Anti-Imperialist tendency, such as Venceremos or the George Jackson Brigade, were making the same breakthrough, the WUO became famous as the example of Euro-Amerlkan armed activity.

Like LSM, “Weather” correctly understood that imperialist social bribery had corrupted the society as a whole. And in their first statement—”You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows”—of June 1969, they began with that point:

“We are within the heartland of a world-wide monster, a country so rich from its world-wide plunder that even the crumbs doled out to the enslaved masses within its borders provide for material existence very much above the conditions of the masses of people of the world... All of the United Airlines Astrojets, all of the Holiday Inns, all of Hertz’s automobiles, your television set, car and wardrobe already belong, to a large degree to the people of the rest of the world.”(5)

This was a political understanding that developed apace with the Sixties youth culture, out of people first made aware by the biting criticism of the New Afrikan Liberation Movement, It was a significant break with the revisionist settler Left which always tried to win mass support by promising to out-bribe imperialism, to provide even more for the Euro-Amerikan masses.

“Weather” went further, taking this analysis into practice. In one of the key WUO speeches made at the SDS Cleveland Conference in August 1969, Billy Ayers took up the accusation often hurled at WUO that “You guys aren’t into serving the people, you’re into fighting the people.” He pointed out:

“We thought that you don’t serve people by opening a restaurant or by fighting for a dollar more; you serve the people, that means all the people—the Vietnamese, everybody, by making a revolution, by bringing the war home, by opening up a front. But the more I thought about that thing ‘Fight the people,’ it’s not that it’s a great mass slogan or anything, but there’s something to it... There’s a lot in white Americans that we do have to fight and beat out of them, and beat out of ourselves.”(6)

The identification of Babylon and the initial refusal to gloss over the corruption that Euro-Amerikans have internalized, was one of the political contributions of the WUO. In these and other political strengths the WUO was representing a new consciousness by the Anti-Imperialist tendency as a whole. WUO had a large current of sympathy, although the organization itself began small and stayed that way. Their communiques were widely reprinted. Supporters existed in local defense committees, food co-ops, drug abuse programs, “counter-culture” newspapers, rural communes, and throughout the university sub-culture. Other small clandestine collectives, usually involved in bombings against government and corporate buildings, were encouraged to form by WUO’s example and call to action. In particular many were moved by WUO’s argument that Euro-Amerikan revolutionaries could not just lay back and let the Third World do the fighting and dying. As Bernardine Dohrn said in “Communique No. 1”: “Black people have been fighting almost alone for years. We’ve known that our job is to lead white kids into armed revolution.”(7)

To understand what happened to the WUO, which chose the terrain of armed struggle, we must analyze them from a political-military standpoint. The first obstacle to understanding “Weather” is its fame, which cast misleading images around it. WUO leaders were headline celebrities, while their organization was discussed and denounced from every political corner of White Amerika. From the beginning the FBI publicly labeled WUO as a terrorist menace. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called WUO “The most violent persistent and pernicious of revolutionary groups.” In his testimony before Congress In March 1971, Hoover said: “investigation has identified over 1,544 individuals who adhere to the extremist strategy of the Weatherman.” Two months later Irvin Recer, Supervisor of FBI Domestic Intelligence, said in a lecture at the Army War College that the WUO were “fanatical revolutionaries.” And Hoover himself raised the WUO to the threat level of the Black Panther Party in his March 2, 1972 testimony before Congress:

“Urban guerrilla warfare by black extremist organizations such as the Black Panther Party, by white radical groups, such as the Weathermen, and by other organized terrorists, is a serious threat to law enforcement and the entire nation.”(8)

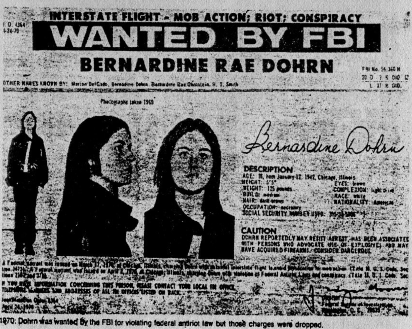

The FBI had put WUO in the “big time” category. In May 1970 it announced “one of the most intensive manhunts in FBI history” had begun for nine WUO leaders. Bernardine Dohrn made the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. A number of WUO cadre went underground on indictments for explosives or conspiracy to start “riots.” By 1972, over 20 WUO cadre were officially listed by the FBI as fugitives.(9)

On their part, most of the revisionist opponents of armed struggle also attacked the WUO as terrorists. As late as November 1981, after the Nyack Brinks arrests, we find the newspaper of Amiri Baraka’s League of Revolutionary Struggle (ML), Unity, still trying to explain WUO as terrorist: “...their terrorist line and isolation from the masses... Groups like the Weather Underground have existed throughout modern history. In Lenin’s time, small groups of educated intellectuals threw bombs and engaged in terrorist activities to ‘excite’ the masses.”(10) This is fairly typical for the Bourgeois Marxist organizations. Similar things were said about the George Jackson Brigade, SLA, Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Brigade, and so on.

The very first thing to understand about “Weather” is that they never were a terrorist organization. This is merely a clinical fact, neither praise nor condemnation. The original Russian terrorists, for example, were called that because they erroneously believed that the fear of assassination could cause the Czarist regime of the 1870s to literally fall apart, to stop governing. They were terrorists because they planned to create real terror—and did, by killing high officials from the Czar himself to the Minister of Justice, police and cabinet officers. This was usually done by throwing powerful, home-made bombs by hand from point-blank range. The courage and revolutionary idealism of these terrorists—among whom was Lenin’s older brother—was legendary, and most of them gave their lives. Or to take an example on the Right, the imperialist death squads in El Salvador are considered terrorist for obvious reasons. Terrorism is a specific type of political-military activity. Nor is it always incorrect. Lenin in his day noted the importance of terrorism and select terrorist units in specific circumstances (although not as the general strategic line of the struggle).

The Weather Underground never tried to kill anyone, never tried to create terror, and never did. Bourgeois Marxists and the FBI misuse such political-military terms for their own reasons. We need to be precise. In the imperialist media the WUO was portrayed as “drug-crazed hippie bombers.” it was an error that the WUO, like the SLA after them, was seduced by its bourgeois media image, playing into and along with it. Its actual military program was the opposite of terrorism. WUO had definite military tactics: carefully selected minor property bombings of government and corporate buildings. Great care was taken that no imperialist police, soldiers or officers were killed. No extensive damage or disruption of overall settler life was done. The WUO bombings were symbolic military actions, deliberately having neither military nor economic effect. They were media propaganda actions, each one selected to both hopefully radicalize the mass movement and to show the WUO’s leading role.

Certainly its most famous single action was the bombing of a washroom in the U.S. Capitol Building on March 1, 1971, in protest of President Nixon’s escalation of the war in Laos. Again, on January 29, 1975, WUO placed a bomb in the third floor washroom, next to the Agency for International Development offices, in the U.S. State Department building, to protest President Ford’s request for increased military aid for the Cambodian and Saigon puppet regimes. These were well-planned media actions, intended (in the WUO’s words about the bombing of the Capitol washroom) “to bring a smile and a wink to the kids and people here who hate this Government, to spread joy.”(11)

So while the FBI and the revisionists have always pictured the WUO as very “extreme,” exceptionally militaristic, it is much more accurate to say that WUO was a typical part of the militant protest movement. Small bombing and sabotage conspiracies, martial arts classes, firearms training, and assorted illegal activities were common in the Movement by that point. The military actions of the WUO, far from being either terrorism or bloody armed adventures, were militant protest activities in step with the sharpening mood of the student New Left.

The contradiction lies in the fact that protest actions, even illegal and violent ones, do not in themselves necessarily constitute a war. What the WUO was doing was not war, despite what it may have thought. While there were continuing wars between the U.S. Empire and rebellious elements within its colonies and neo-colonies, there was not yet revolutionary war between the settler Left and “their” Empire. This is simply a matter of fact. We can see it in the de facto agreement by the WUO and the imperialist security forces not to shoot or harm each other.

We can see it in the levels of combat. In 1972 the FBI’s official summation for the year on urban guerrilla actions (everything from ambushing police to expropriations, bombings, and setting up weapons caches) places the total at 195 actions, with eleven police killed in action and forty-three wounded by guerrillas. Of the 195 actions only 14 were attributed to Euro-Amerikan revolutionaries (including the WUO). The B.L.A. alone accounted for 25 actions, with the PG-RNA and other similar nationalists credited with 20. More to the point, almost all the combat with security forces was by the New Afrikan Liberation Movement. While they were fighting a very uneven, almost one-sided, war, sustaining heavy casualties and losing ground to multi-leveled counter-insurgency, the WUO was doing periodic protest bombings while carefully neither giving nor taking casualties. This is a reflection of the general stage of consciousness and struggle in the U.S. oppressor nation.* It is just important now, long after those events, to be clear that the U.S. New Left was not engaged in revolutionary war—no matter how much they sympathized with or supported the national liberation wars that others, the Vietnamese or New Afrikans, were locked in.

* Those small collectives that did attempt military- political activities beyond the protest level—such as the George Jackson Brigade and Sam Melville-Jonathan Jackson Brigade—found themselves abandoned by the Movement. The WUO itself was none too enthusiastic about embracing Euro-Amerikans who were actually trying to do combat.

Like LSM, the Weather Underground took up proletarian internationalism but in a subjective way. These were new concepts to the settler nation, and the 1960s protest movement as a whole took up solidarity with national liberation struggles with great enthusiasm, but in fad-ish, one-sided and undeveloped ways. WUO’s uncertainties about revolutionary war had their roots in political confusion about internationalism as it actually applied to the here and now of the continental Empire. What does it mean to “follow Third World leadership”? Can anti-imperialism, which is international, have national form? How can European settlers overthrow privilege and parasitism?

In a settler Empire, one that is both a “prison-house” of Third World nations and peoples as well as the No. 1 imperialist power, for young revolutionaries to be uncertain about proletarian internationalism inescapably means being in practice uncertain about parasitism, uncertain about solidarity, and so on. WUO, LSM, and the whole rest of the New Left envisioned that there would be only one united revolution in the U.S. Even in separate movements, they believed that New Afrikans, Euro-Amerikans, other Third World peoples (in that order of importance) would achieve de facto unity in overthrowing the only enemy—the U.S. ruling class. This not only had a reasonable logic to it, this was what the “heaviest” Black revolutionaries they were allied to were saying. Huey Newton and the BPP explicitly said that everyone was united under BPP leadership in one revolution “against Fascism.” John Watson of the Detroit League of Revolutionary Black Workers also told them that they were united in one revolution, albeit unequally since the Black vanguard would “do the chopping” while the Euro-Amerikan supporters would meekly follow behind and “do the whittling.” Malcolm and nation-building had been left behind. And wasn’t this “following Third World leadership”?

The effects of this confusion on the WUO’s political-military development was drastic. WUO believed that it was fighting an inevitably victorious revolutionary war—although as an organization they themselves were not doing any such thing—because they looked to the Black Liberation Movement to do it for them. As the initial “You Don’t Need a Weatherman...” document makes plain, even the projected revolutionizing of White Amerika would be accomplished with or without settler effort by the Black Revolution overthrowing U.S. imperialism as a whole. In their view, the main task of settler radicals was only to try and keep up enough with the New Afrikan Liberation Movement so that Euro-Amerikans kept some role in the united revolution. So while LSM saw themselves being carried to revolution by Afrikans in Angola and Mozambique, WUO saw themselves being carried to revolution by Afrikans in the U.S. Empire. “Hitching a ride on the BLM.” WUO’s “You Don’t Need a Weatherman...” said:

“...if necessary, black people could win self-determination, abolishing the whole imperialist system and seizing state power to do it, without this white movement... Blacks could do it alone if necessary because of their centralness to the system, economically and geo-militarily, and because of the level of unity, commitment and initiative which will be developed in waging peoples’ war for survival and national liberation... Already, the black liberation movement has carried with it an upsurge of revolutionary consciousness among white youth... It is necessary to defeat both racist tendencies: 1) that blacks shouldn’t go ahead with making the revolution, and 2) that blacks should go ahead alone with it. The only third path is to build a white movement which will support the blacks in moving as fast as they have to and are able to, and still itself keep up with that black movement enough so that white revolutionaries share the cost and the blacks don’t have to do the whole thing alone.”(12)

Again like LSM, the WUO looked to external forces outside themselves and outside their nation to make their revolution. This view was an Achilles heel, which turned internationalist recognition of the leading world role of national liberation struggles into a revolutionary parasitism. From there further sliding, into opportunism and survivalism, could not be resisted. It became easy to let others do the fighting and dying, so long as the WUO’s media reputation was maintained. Neither solidarity against the U.S. Empire nor a Euro-Amerikan revolutionary movement could be built on that quicksand.

The issues are not tactical military ones, of more or less shooting. For example, the WUO’s central justification was that they were leading white youth to finally unite on the world battleground with the Vietnamese, Cubans, Afrikans and all the oppressed fighters combating imperialism. This was to be the first real solidarity. As Bernardine Dohrn said in “Communique No. 1”: “Hello. This is Bernardine Dohrn. I’m going to read A DECLARATION OF A STATE OF WAR... We celebrate the example of Eldridge Cleaver and H. Rap Brown and all Black revolutionaries who first inspired us by their fight behind enemy lines for the liberation of their people.

“Never again will they fight alone.”(13)

Now, in the first place, the New Afrikan Revolution wasn’t “alone,” since it represented 35 million people and was tied to other revolutionary struggles and nations on every continent. While the sentiment is perhaps progressive, it isn’t true that if Euro-Amerikans aren’t with you then you are “alone.” Perhaps the reverse would be closer to what the WUO really meant—without the Black Revolution then WUO felt “alone.” While the WUO maintained a public façade of armed solidarity, this was practically impossible since the national liberation struggles were at war and the WUO and the settler New Left were not. Symbolic bombing actions were done to protest killer cops in New York, to protest the assassination of George Jackson, and so on. Individually these actions might seem to have merit. But as a whole they were only used as cover for false internationalism, for lack of solidarity.

WUO consistently refused to aid the BLA or other guerrillas in practice, refused to help hide fugitives, and eventually refused to even aid imprisoned fighters. All of this was done secretly, while the public media show of “bold revolutionary action” and solidarity was kept up. In other words, the difference in practice between the revisionists and WUO was that the revisionists didn’t offer solidarity while the WUO pretended to. The WUO leadership was only carrying out the logic of its real situation, since if the organization—which was not at war—would have been dragged into the “free-fire zone” it would have been in a very different situation. In a classic case of survivalism, the WUO leadership placed their own personal safety as the highest priority, equating it with the survival of the Revolution.

Bernardine Dohrn herself, in her political self-criticism, details this:

“This is Bernardine Dohrn. I am making this tape to acknowledge, repudiate and denounce the counterrevolutionary politics and direction of the Weather Underground...

.......

‘We denied Black and Third World organizations aid and support they requested and rejected offers of meetings and joint work unless they were completely on our terms. That is, our security and our safety were placed above that of Third World and Black organizations. This was especially true of struggles under heavy attack by the state, under severe and murderous repression. I characterized these groups as left-sectarian, dangerous and threatening to us. By placing our protection and resources above the revolutionary principles of proletarian internationalism, we in fact operated to control Third World movements by making support and resources available only on our terms...

“Meanwhile, this organization refused to seek out or recruit revolutionary women fugitives. We characterized these women as anti-men, anti-communist, anti-Marxist-Leninist. Actually, the central committee feared their effect on women in the organization... We attacked and defeated a tentative proposal for a women’s underground to carry out anti-imperialist and revolutionary feminist armed struggle.

“While denying support of Third World liberation, to revolutionary armed struggle forces and to revolutionary women fugitives, we used resources and cadre’s efforts to support opportunist and bourgeois men fugitives. The most glaring example of this is our support in the form of time, money, cadres, of Abby Hoffman, a relationship which produced media attention for us, through the articles in New Times and his TV program.

.......

“By the summer of 1975, the attack on the women’s movement and feminist politics was naked and bitter... This attack on women and the women’s movement was carried out in a very personal way against women most identified with the women’s movement. The consequences were the collapse of several women’s organizations, and the withdrawal of anti-imperialist women from women’s political work. it resulted in taking women out of anti-rape work and the defense of Third World women like Joann Little, lnez Garcia, and Yvonne Wanrow.* It meant an end to women’s health care projects, abortion and anti-sterilization work, and work with women prisoners.” (14)

* These were women—Black, Chicano and Indian respectively—who had been imprisoned for armed self-defense.

WUO’s inability to go forward Into armed struggle was directly related to two problems:

1. There was no ready made proletarian base in the u.s. oppressor nation. There was, In fact, no social base at all for revolutionary war except for a small sector of radicalized petty-bourgeois youth. At the December 1969 Flint “War Council,” one WUO spokesperson said that Euro-Amerikan involvement in Revolution was so irrelevant that after the Revolution they would be under a Third-World dictatorship from abroad, “an agency of the people of the world.” But to go to war with no idea of where the mass social base was to root the struggle in, was daunting. Would-be Euro-Amerikan guerrillas could not base themselves in the Chicano community, for example. And WUO never really understood that no revolutionaries find conveniently ready-made, pre-packaged social bases but must develop and build the masses and themselves in the same process.

2. WUO took pleasure in speaking of itself as white shock troops, as “vandals” and “crazy motherfuckers.” But in reality they never accepted the position of’ being soldiers (communists). The small organization considered itself the only true leadership over the entire settler movement. Not soldiers at all, but a privileged elite of petty-bourgeois leaders and headquarters staff. As an organization WUO was unwilling to face death, unwilling to accept the possibility/probability of being physically wiped out. This had roots not only in WUO’s petty-bourgeois character (which was unavoidable) but in the yet unanswered problems of making revolution in a non-proletarian oppressor society. These difficulties were hardly unique to WUO or to any organization or faction in the New Left.

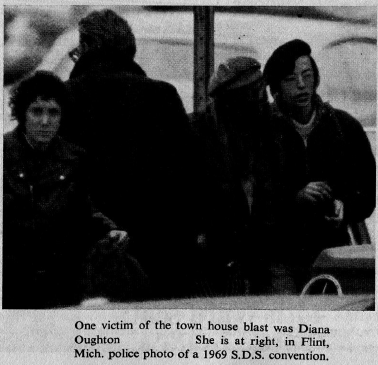

For those reasons WUO never seriously approached armed struggle. And indeed, soon began backing further away from it. This was particularly true after Townhouse, the March 1970 incident in which three Weather cadre were killed in a dynamite accident. A pattern emerged: periodic property bombings would be done. WUO communiques threatening major blows would be issued—everything from “attacks will be carried out on pigs” to promised raids on prisons to free H. Rap Brown and the Soledad Brothers. Which, of course, never happened. All this was to give the impression of a “heavy” revolutionary force. Meanwhile, the WUO Central Committee was trying various other strategies to get out of their dilemma and win a popular base of support among Euro-Amerikans. This dishonest and ambivalent situation finally led to the WUO abandoning clandestinity, which was useless to them except as a publicity gimmick, and taking up the program of legal reformism. WUO had exploited the prestige of armed struggle without ever entering it strategically. Its token bombings were used as a tactic to cover up for this.

At the beginning, in 1969, WUO saw revolution as a free gift from the New Afrikan Liberation Movement. As its contribution WUO hoped to command a small army of white drop-outs—”greasers,” motorcycle gangs, dopers, high school rebels—irresistibly drawn into the chaos created as New Afrikans overthrew the U.S. Government. They initially saw armed struggle just as violent disruption, creating havoc. Anything that disrupted society was revolutionary. The slogan was “The bigger the mess the better.” Weatherleaders still considered themselves as imperialism’s bad children, thumbing their noses at society by shocking behavior. The mood of that period can be recaptured in Bernardine Dohrn’s speech to the last public SOS- Weather gathering, the December 1969 “War Council”:

“Since October 11 we’ve been wimpy on armed struggle... We’re about being a fighting force alongside the Blacks, but a lot of us are still honkies and we’re scared of fighting. We have to get into armed struggle... We were in an airplane, and we went up and down the aisle ‘borrowing’ food from people’s plates. They didn’t know we were Weathermen; they just knew we were crazy. That’s what we’re about, being crazy motherfuckers and scaring the shit out of honky Amerika.”(15)

Within six months of going underground in 1970 there was a clearer grasp of their difficult situation. A definite strategy emerged: to find a base of popularity in the petty-bourgeois drug subculture. While WUO opposed truly rebellious cultural forces being born—most notably Women’s Liberation—it glorified drug use (and implicitly the petty-bourgeois drug traffic and subculture) as revolutionary. Hard words like socialism and communism faded out of political statements, replaced by vague hymns to drug use. This also began their practice of opportunistic deals with various drug celebrities.

On September 13, 1970, the WUO assisted LSD “guru” Dr. Timothy Leary’s escape from a minimum security prison in California. Their ties to Leary were put forward as revolutionary armed struggle.* In Communique No. 4, WUO glorified Leary as a supposed “political prisoner, captured for the work he did in helping all of us begin the task of creating a new culture...” The communique went on to say: “LSD and grass, like the herbs and cactus and mushrooms of the American Indians and countless civilizations that have existed on this planet will help us make a future world where it will be possible to live in peace.” There was no mention of socialism or communism.

* Leary went into exile in Algeria with the Cleaver wing of the BPP. He and Eldridge Cleaver held many “revolutionary” press conferences together. That was the period of the WUO-Cleaver media alliance.

Not only was the model of a drugged society laid off on Indians, but the communique dragged in the names of the NLF, Al Fatah, PFLP, etc. as groups the WUO was “with.” That was a cover-up, to fend off questions as to why an organization supposedly started to give armed solidarity to the oppressed should free a petty-bourgeois drug “guru” as Its first major action. The communique dishonestly ends:

“With Rap Brown, Angela Davis, with all Black and brown revolutionaries, the Soledad Brothers... Our organization commits itself to the task of freeing these prisoners of war.

“We are outlaws, we are free!

“Bernardine Dohrn”

Already the “solidarity” with oppressed nation revolutionaries was a conscious lie, part of the cover-up. WUO had no plans to or intentions of sacrificing itself freeing P.O.W.s. A revolutionary underground supposedly set up to do armed struggle in solidarity with national liberation, had within months turned into its opposite. Not solidarity, but rip-off. Settlerism not overcome, but still dominant even in an armed underground group.

The trend of the Leary action was solidified in the pivotal New Morning—Changing Weather document of December 1970. New Morning conspicuously downplayed armed struggle and support for national liberation. Instead, the petty-bourgeois drug subculture was appealed to as the supposed base of a “revolutionary culture,” a youth nation:

“This communique does not accompany a bombing or a specific action. We want to express ourselves to the mass movement not as military leaders (our emphasis—ed.) but as tribes at council. It has been 9 months since the townhouse explosion. In that time, the future of our revolution has been changed decisively.”

New Morning said: “But the townhouse forever destroyed our belief that armed struggle is the only real revolutionary struggle... The deaths of three friends ended our military conception of what we are doing.” instead, WUO praised the vanguard role of the alternative culture: “They’ve moved to the country and found ways to bring up free wild children. People have purified themselves with organic food, fought for sexual liberation, grown long hair. People have reached out to each other and learned that grass and organic consciousness expanding drugs are weapons of the revolution.”(17)

The Panther 21, leading cadres of the N.Y. BPP who were imprisoned in a major COINTELPRO operation, answered New Morning in an open letter. “We, of the Panther 21, take this opportunity to greet you with a spirit of revolutionary love and solidarity... This letter is to acknowledge your actions—and like how we have watched your growth—and to relate to you how we have felt revolutionary joy on both accounts. This letter Is also a response to your latest communiqué—“New Morning—Changing Weather.” In it we can sense and feel your frustration and sense of isolation. We know the feeling well, having felt it ourselves for the last 21 months. We also very keenly feel the loss of direction, the confusion and chaos that is running rampant out there... So from our experiences, we are responding to your communique because although we can fully understand where you are coming from—we sensed a certain mood and saw certain statements in your communique that sent chills up our spine... We can also see that you feel—and rightfully so—the need for more support from the mother country youth. But we feel that most of the mother country youth culture communes smack heavily with escapism—a danger you must be aware of and guard yourselves against.”(18)

The Panther 21 urged WUO not to give up, to continue armed struggle. WUO refused to answer or discuss the criticism, since their whole strategy was to back away from armed struggle while still claiming its prestige.

The New Morning—Changing Weather line helped cover for the retreat to the sidelines, but it was not a guide to base-building. Between 1970 and 1973 the mass movement collapsed still further, while the alternative youth culture developed in a patriarchal, hip-capitalist manner, cynical to struggle and withdrawn into their own individualized concerns. The obvious irrelevance of New Morning led the WUO to jump to another strategy in 1973-74, centered on the publication of the book Prairie Fire. The book was met with great interest in the Movement. Thousands of people eagerly read it. And not only because a political book from the most celebrated radical bombers in Amerika had curiosity value. While Prairie Fire was ideologically outdated for the time, it nevertheless had important strengths. We must remember that in 1974 the settler protest Movement had essentially evaporated. The New Left itself was self-destructing in the sterile, shrinking “party-building” debates of would-be Maoists. Everything good from the ‘60s seemed to be dying. For some, Prairie Fire seemed to be a reaffirmation of the vital links between armed struggle and popular mass movements, settler counter-culture and the rebellious Third World.

Prairie Fire was subtitled The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism, and covered everything from a capsule history of settler reform movements to sections on the Palestinians, PAIGC, BLM, Native Amerikans, Women’s Liberation, and so on. An entire chapter was devoted to the Vietnamese, as the most important struggle for Euro-Amerikans (“All for Vietnam”). The book sharply broke with the New Morning line. Armed struggle was verbally affirmed:

“We are a guerrilla organization. We are communist women and men, underground in the United States for over four years... Our intention is to engage the enemy... to wear away at him, to harass him, to isolate him, to expose every weakness, to pounce, to reveal his vulnerability.”(19)

The petty-bourgeois drug subculture was no longer uncritically praised. in a sharp turn-about Prairie Fire criticized people with “a flippant attitude toward consciousness-expanding drugs” (although WUO carefully stopped short of opposing drug use by settler youth). The book evaluates WUO’s chosen social base in sober terms. Noting that a once-positive development of “nomads, communal semi-hustlers, sharing a certain sense of being alien to and in opposition to the U.S. imperial way of life,” had by 1973 “withdrawn to rest on its privileges, dissociating itself from active opposition to racism...”(20)

Early in Prairie Fire the WUO explicitly repudiated its New Morning line, admitting that they had retreated from struggle:

“We have to learn from our mistakes...

“Reaffirming the importance of mass movement and political as well as military struggle, we wrote New Morning in December 1970. But New Morning gave uncritical support to youth culture and came to represent a repudiation of revolutionary violence. The Panther 21 wrote a generous and fighting criticism of New Morning from prison, which warned us against putting down our weapons. They correctly pointed to the necessity to continue to fight and our need to teach our people to fight. By failing to answer, we lost an opportunity to engage in dialogue with these brave and dedicated comrades.”(21)

Often on target in its anti-imperialism, the book summed up many of the weaknesses but also the political gains of the young settler Movement:

“Our movement must discard the baggage of the oppressor society and become new women and new men, as Che taught. All forms of racism, class prejudice, and male chauvinism must be torn out by the roots. For us, proletarianization means recognizing the urgency of revolution as the only solution to our problems and the survival of all oppressed people. It means commitment, casting our lot with the collective interest and discarding the privileges of empire. It means recognizing that revolution is a lifetime of fighting and transformation, a risky business and ultimately a decisive struggle against the forces of death.”(22)

Prairie Fire’s impact temporarily strengthened the WUO, rallying supporters and winning new friends. WUO tried to be a real presence at the first national Socialist Feminist Conference in 1975. A public organization, the Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, was formed to gather supporters and be the legal, aboveground arm of WUO. Prairie Fire had sent out a call: “At this time, the unity and consolidation of anti- imperialist forces around a revolutionary program is an urgent and pressing necessity.”

Yet, three years after the publication of Prairie Fire the WUO broke up, discredited as a leadership organization. Their crisis was precipitated by the new “revolutionary program.” On the surface it appeared as a more developed synthesis of Anti-Imperialist themes—solidarity with national liberation, armed struggle, revolutionary culture. Underneath that deliberate surface impression, the Prairie Fire line totally reversed the original direction of the Weather Underground. Where at first the WUO leadership played with being “guerrillas,” and then played at being “outlaws,” by 1974 they had decided to rejoin the reformist left and play at being “Marxist-Leninists.”

Part of Prairie Fire’s popularity was that it subtly catered to the settler nationalism that U.S. Bourgeois Marxism had always been infected with. The FBI commented in a report for other security agencies:

“The Weather Underground has adopted, to a degree, more of an ‘old-left’ Marxist line in recent months and has gained considerable support in the process.” We can easily trace the surfacing of these reformist politics from Prairie Fire’s class analysis, to its solidarity program, to its strategy for the Movement.

1. In Prairie Fire, the WUO leadership put forward the new strategy of representing the whole settler population (except for a small imperialist class), as their base of support. They sharply criticized their own earlier periods in which they did not identify with the white majority:

“We were wrong in failing to realize the possibility and strategic necessity of involving masses of people in anti-imperialist action and organization. We fixed our vision only on white people’s complicity with empire, with the silence in the face of escalating terror and blatant murder of Black revolutionaries. We let go of our identification with the people—the promise, the yearnings, the defeats.”(23)

In its discussion of “The Changing Nature of the Working Class,” Prairie Fire identified itself with WUO’s supposed working class base for revolution: “The great mass of the white collar workers, clericals, service people, teachers and professionals are underpaid, exploited... They comprise the majority of the U.S. workforce not at home.” It is specifically noted that these settlers were not middle class, but working class.(24)

Once “Weather” saw the settler white-collar, suburban masses as corrupted and highly privileged, oppressors themselves comprising a loyal base for imperialism. That view was too radical, and was unpopular with settlers. Now WUO had reversed itself. This same settler white-collar majority were supposedly “underpaid, exploited” workers. That view was much more popular with settlers. And that was the usual Bourgeois Marxist narcotic to help “identification” with those who were indifferent to genocide and lived lives of “complicity with empire.”

2. Prairie Fire revealed a problem for WUO. It had two conflicting sets of friends to identify with. On the one hand, it had been called into being by the New Afrikan Liberation struggle, and its members had always pointed to the leading and heroic role of Black fighters. On the other hand, its would-be social base included the settler majority that supported “escalating terror and blatant murder of Black revolutionaries.” WUO found itself identifying with both sides of the liberation war. They found their solution in the deepest traditions of their people. If President Johnson had tried “using the nigger against the gook,” then WUO could also do the same (only in reverse). Or “All for Vietnam.” Just as today the white Left declares that internationalism means solidarity with Central Amerikan struggles, while paying only lip- service to liberation struggles within the “u.s.a.”

This was a very heavy matter. Bernardine Dohrn said in her 1976 self-criticism: “We pitted other national liberation struggles against the Black movement. For a long time it was Vietnam.” “Weather” members and supporters had always been proud to stand beside the Vietnamese people. Theirs was genuine pride that their organization had never abandoned Vietnam as so many had. The new ‘70s fad of pseudo-Maoism was eating away at solidarity with heroic Vietnam, and the Movement needed the WUO to help strengthen Anti-Imperialism. Weather Underground leadership cynically exploited that love and respect that its people had for Vietnam. Not just to promote themselves. But to slyly oppose the most dangerous and unpopular path of solidarity with Black Liberation—“Using the gook against the nigger.”

WUO pointed out: “The Vietnamese struggle is the most significant political event of our generation. Understanding the history of the Vietnam War is a key to understand the present world situation, the present u.s. governmental crisis, the present possibilities for the revolutionary movement here, and a correct anti- imperialist perspective. This is the era of national liberation, and for most of the past fifteen years, Vietnam has been the leading force in this struggle.”

But this general analysis was twisted in being applied to the particular situation here, in being brought home: “The seriousness of our threat was growing. The killings of students at Jackson State and Kent State had a significant effect on the youth movement. The war was brought home... During that time, the anti-war movement reached its greatest strength and the largest and most militant demonstrations took place. Inspired by the Black Panthers and other Black fighters, many whites such as Sam Melville, Cameron Bishop, the New Year’s Gang in Madison, and ourselves began building armed struggle...

"ALL FOR VIETNAM”

“The vanguard nature of Vietnamese liberation in the past decade means that we can approach the difficult question of class analysis, consciousness and potential, by looking at how various groups within society were affected by anti-war struggle. This way we avoid an idealist or opportunist class analysis, and begin with our understanding, based on practice, of the leading anti-imperialist forces in society. Black and Third World people, and young people—especially students and members of the armed forces—responded to the Vietnam War in the most consistently principled way... Support for the leading force in the fight against the enemy is the essential and necessary content of proletarian internationalism here and now.

“Many organizations pay lip-service to the anti- imperialist struggle. But those movement organizations who, in practice, did not come to give full support to the Vietnamese as the main priority of class struggle made a serious error (our emphasis—ed.). This was especially true during the 1972 Final Offensive, when—between the launching of the offensive on March 31, 1972 and the signing of the Cease-Fire Agreement on January 27, 1973—the slogan of the movement should have been: ‘All for Vietnam!’ By this measure we criticize our own practice during the final offensive, when we organized under the slogan, but were not successful in carrying out our full program.”(25)

We quote this passage because it helps us to understand what oppressor nation anti-imperialism is and is not. Prairie Fire deliberately blurred and tried to erase the distinction between anti-war and anti- imperialist. Between the broad Anti-War Movement and the small Anti-Imperialist tendency. This trick made it sound as though there were a mass, anti-imperialist struggle of millions of settlers, which was not true. The U.S. Anti-War Movement brought together many widely diverse political points of view, united only by the common demand that U.S. combat troops be withdrawn from Indochina. Which is why the larger Movement came to an end once U.S. troops were finally withdrawn. Most settler critics of the War were still overall pro-imperialist, opposed to national liberation and socialism particularly inside “their” Empire.

The WUO slogan “All for Vietnam” as “the main priority of class struggle” falsely defined internationalism solely in terms of the Anti-War Movement. That slogan for the period 1971-73 ignored a concrete analysis of the actual struggle going on here within the continental Empire. It actually opposed national liberation.

As we know, the main aspect of that period here was the attempt by the oppressed nations within the continental Empire to break through to a higher level of struggle, to move from spontaneous rebellion and resistance to national liberation. The particular feature of that period was the attempt, by movements being decimated in the Amerikkkan free-fire zone, to move from Civil Rights and self-defense to armed guerrilla action and self-government, even initial liberation of some National Territory. These attempted breakthroughs were turned back by U.S. Imperialism with qualitative losses for the anti-colonial insurgents. Anti-Imperialism within the continental Empire was defeated. This period was pivotal, then, the deciding round in the anti-colonial rising of the 1960s.

By 1972 the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika, representing the revolutionary nationalism of the Black Nation, had been crushed in its attempt to set up a temporary capital on New Afrikan-owned land in Mississippi, symbolizing their intention to Free the Land. On August 18, 1971, Jackson Police and FBI captured two RNA residences in Jackson, taking three casualties in the process. The defense case of the RNA-11 began. Almost thirty of the most dedicated RNA cadre were in the state prisons of Louisiana and Mississippi. In response to the RNA-11 arrests, the largest New Afrikan demonstration in the history of Jackson took place. The settler Anti-War Movement and New Left did not defend or support the PG-RNA in any way. Many felt that since the PG-RNA were separatists they “deserved” no support. WUO refused to recognize the Provisional Government; refused to oppose the counterinsurgency campaign against it; refused to give political or material support to the defense case.

By 1973 the attempt to launch the New Afrikan guerrilla struggle, using the “autonomous and decentralized” ex-BPP units known as the Black Liberation Army, had received serious set-backs. The struggle did not end, however. In 1973 BLA units had twelve engagements with police, inflicting nineteen casualties. Looking back, the BLA-CC wrote:

“...The spark we hoped would start the fire that would burn Babylon down was extinguished by State propaganda organs and special anti-guerrilla squads. Many comrades moved to the South hoping to establish a southern base; this too failed because we lacked knowledge of terrain and people, so again we moved back to the cities, this time as fugitives with little popular support among the masses. Our primary activity at that period was hiding out and carrying out expropriations. With the deaths of Woody and Kimu we launched assaults against the police that set them on edge; their counter-attack saw us at the end of 1973 with four dead, over twenty comrades imprisoned in New York alone. In New Orleans, Los Angeles, and Georgia, B.L.A. members were taken prisoner by Federal agents working with local police to crush the B.L.A.”

In private communication the B.L.A. had asked WUO for political-military support: assistance for fugitives such as Assata Shakur, other forms of practical cooperation, political campaigns to help impede the FBI counter-insurgency campaign. WUO refused totally. WUO leadership adopted their position that New Afrikan guerrillas were “dangerous and threatening to us.” This position was kept secret so as not to discredit WUO.

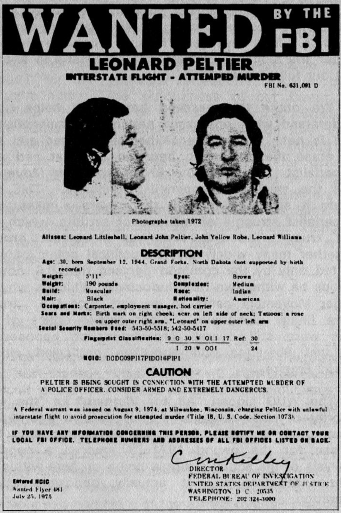

The U.S. reconquest of liberated Wounded Knee on May 9, 1973 was another nodal point. A.I.M. fighters from many Indian nations had helped Oglala Sioux patriots assert armed self-government under U.S. military siege. Despite much public sympathy, imperialism not only crushed nation-building, but launched a Phoenix program to assassinate or otherwise “neutralize” grass-roots A.I.M. cadre and supporters. Hundreds fell. A wave of terrorism swept the Plains, as Indian patriots kept being found dead in “accidents,” “suicides” or unexplained shootings. A news white-out by imperialism, in which the New Left cooperated, shielded their Phoenix program in silence.

When Anti-Imperialism was defeated, thrown back, within the oppressed nations it signified a general reversal for all revolutionary forces within the continental Empire. The settler Anti-Imperialist tendency suffered a profound defeat as well. It was not Vietnam that was ultimately decisive here. As we can see from the fact that the Vietnamese victory coincided with the collapse of the New Left. The settler New Left tended to picture anti-imperialism as a “Solidarity Supermarket” where each season well- meaning Euro-Amerikans could stroll the aisles picking and choosing from among the many liberation movements of the world which ones they wanted to “support,” depending on the latest fads. So-called internationalism was trivialized to resemble a recreation or a hobby. Rather than being guerrillas, being revolutionaries in deeds as WUO had once set out to do.

There were concrete reasons for the failure of the Anti-Imperialist tendency to join the struggle in the decisive period. First and foremost, the national liberation movements were themselves still ill-organized, and politically unable to give correct leadership to their alliances. U.S. oppressor nation anti-imperialists were stunned at the disappearance of the mass Anti-War Movement, unorganized to carry out revolutionary tasks in the face of the imperialist counter-offensive.

So as decisive Anti-Imperialist battles were being fought here, settler Anti-imperialism found itself standing safely on the sidelines as spectators. And there with everyone else was the WUO, covering up by shouting “All for Vietnam.” Could there be a more profound defeat? While the mass Anti-War Movement was the sheltering “sea,” the rich political current in which Anti-Imperialism grew, settler Anti-Imperialism was born out of the challenge and example of the New Afrikan Liberation Movement. Vietnam was indeed the pivotal world confrontation between socialism and imperialism, but it was not a substitute for the specific revolutionary tasks of every nation and people.

Babylon was the battleground for Euro-Amerikans as well, on one side or the other. Settler anti- imperialists had rightfully aspired to fight side-by-side with the oppressed. To have, at the decisive moment, politically abandoned anti-colonial risings was to lose their own heart and soul. What function did settler Anti-Imperialism have if it could not raise a hand against the raging imperialist counter-insurgency? What was left was a stillborn movement, a hollow shell of verbal anti-imperialism.

3. WUO’s final strategy for the Movement was to give up the last remaining vestiges of Anti- Imperialism, and to regain settler popularity by leading a mass, legal reform movement. WUO planned to co-opt all the dissident causes within the continental Empire into one gigantic public movement, whose unifying focus would be broad economic demands. Prairie Fire urged its readers to unite everyone “Against The Common Enemy”:

“We can foresee a time of food riots, unemployment councils, tenants anti-eviction associations, neighborhood groups, anti-war organizations. The left must organize itself to understand the continuing crisis of our times and mobilize the discontent into a force for freedom.

“Organize poor and working class people. Go to the neighborhoods, the schools, the social institutions, the work places. Agitate. Create Struggle...”(26)

Settler trade-unionists, welfare mothers, disabled persons, Asians, New Afrikans, Chicano-Mexicanos, Puerto Ricans, Native Amerikans, lesbian and gay activists, drug dealers, university professors, prisoners, doctors and nurses, settler community organizers, civil libertarians, PTA leaders, the BLA, lawyers, antiwar activists, would all hopefully combine into one public reform movement under the supreme leadership of the WUO. Since it would serve no purpose any longer, clandestinity and even token military actions would be abandoned. That was the final strategy of the WUO, that guided their activity from 1974-1977.

To promote this reformist strategy, Prairie Fire was written to falsely picture the Euro-Amerikan people as not only “underpaid” and “exploited,” but as being anti-imperialist. Confusing the difference between the mass Anti-War Movement and the small Anti-Imperialist tendency did that. It was also necessary to disguise how much settlers hated Black Liberation (“dangerous and threatening to us”) and were indifferent to genocide. To do this Prairie Fire, while paying lip-service to the Black Nation, downplayed and even whited-out the New Afrikan Liberation struggle. For example, in the passage about bringing the war home WUO lists the two major campus repressions of 1970 as important events in the development of the settler Anti-War Movement:

“The seriousness of our threat was growing. The killings of students at Jackson State and Kent State had a significant effect on the youth movement The war was brought home...”(27)

That was an amazing lie, even for the WUO. It was also a revealing lie. We can compare the Euro-Amerikan response to the two separate repressions, at the very peak of student Anti-War militancy:

KENT STATE (OHIO):

* May 4, 1970: National Guard fires on anti-war demonstration, shooting down thirteen settler youth (killing four).

* Major political issue, front-page news. New York Times gave it a 4-column wide headline and 51 inches of copy.

* Settler youth outraged. Storm of protest both spontaneous and organized by Movement. Demonstrations held at 1350 schools. 536 schools closed by student strikes. Violent demonstrations at 73 schools. 169 bombings and arson attacks on government and war-related buildings.

JACKSON STATE (MISSISSIPPI):

* May 14, 1970: State and local police machine-gun a dormitory at Black college, shooting down fourteen Black students (killing two).

* Treated as minor event. New York Times had short, 6-inch story.

* Settler youth indifferent. Movement opposed, but unable to organize protests. Only 53 school demonstrations, most of them at Black colleges.

WUO bombs National Guard office in Washington, D.C. to protest both Kent and Jackson State repressions.(28)

The Vietnam wasn’t “brought home,” as Prairie Fire said, to Jackson State. The fourteen New Afrikan students were shot down because of their own war, their own liberation struggle. That is why revolutionary nationalism popularized the slogan: “Amerikkka Is the Blackman’s Battleground.” WUO was trying to slide around the uncomfortable truth that there was also a battleground right here, on which everybody had to choose their role. They arrogantly sought to erase the difficult lessons of the Black Revolution. And their own founding (“We’re about being a fighting force alongside the Blacks...”)

Publication of Prairie Fire was followed by more military actions. In 1975 there were four WUO property bombings: January 29th at the State Department in Washington (and a bomb that didn’t go off in Oakland); June 16th at the New York City branch of Banco de Ponce, in support of Puerto Rican cement workers strike; September 5th in Salt Lake City at Kennecott Copper Corp., in protest of the overthrow of the Allende regime in Chile. At the same time a new WUO political-military document supposedly giving guidelines for protracted war was put out.

Not only was this renewed military activity put on after the WUO’s 1973-1974 decision to adopt building a legal reform movement as the main revolutionary strategy, but while it was going on the WUO Central Committee decided to give up and surface as soon as possible. In other words, irregardless of what the WUO military cadre thought they were doing, their bombings were only used to oppose armed struggle.

When we think about it, this is not so hard to comprehend. The Weatherleaders had few credentials, other than personal fame, now that the ‘60s campus revolt had ended. They had no record of organizing new settlers, of providing communist leadership, of any accomplishments other than their fame as “white guerrillas.” So they needed a military show to give themselves a renewed media fix, to get enough leverage within the Movement to pull off their new schemes.

WUO’S strategy was named “inversion.” Under “inversion” lawyers were found to prepare for possible trials after surfacing. Led by Leonard Boudin, radical lawyers issued a public call for amnesty for the Weather fugitives. An anti-leadership critique by the “Revolutionary Committee WUO” charged “Overtures were made to the Democratic Party in connection with break-ins against family and associates of the WUO. This provided the possibility of deals in return for the trials being a lever for purging Nixon people in the Justice Department and the FBI.”

A full-length documentary film, “Underground,” was done of the Central Committee to promote their new image as peaceful-minded middle-class settlers loyal to their people. Yippie celebrity Abbie Hoffman, arrested while selling cocaine, was given aid as a fugitive in return for his giving the WUO a media endorsement on a network television interview. Soon the “Weather” leaders hoped to end their underground and resume fully legal settler political life.(29)

In the Spring of 1975 WUO published Politics in Command, their new political-military doctrine. Its outer appearance of armed struggle was just a thin coating, designed to get people to swallow its poisonous ideas. On the one hand it smoothly quoted or paraphrased lessons of revolutionary war plucked from Chile, Uruguay, Vietnam, and Cuba. It said: “We are at an early stage of protracted revolutionary war. We need a strategy to last, to grow and to organize for many years to come...” Yet it never said what that strategy was.

Instead, WUO planted poisonous little barbs like: “...a comparatively small sector of the population actively supports armed struggle... the test of actions is primarily the ability to win people.” The implications led in an obvious direction. The best armed strategy was no armed strategy. If armed actions should be judged “primarily” on the basis of their popularity, and if they are unpopular... in the same vein, Politics in Command finished by stressing the need for an “open,” “legal” and “peaceful” revolutionary—working hand-in-hand with the armed struggle! It isn’t hard to catch the drift. Politics in Command tried to use WUO’s prestige as supposed fighters to undermine political confidence in armed struggle, to soften up people into surrendering along with the WUO leadership.(30)

The next-to-final step in “Inversion” was the attempted launching of the WUO’S grand reform coalition, representing the settler Left, assorted Third World activists and groups, and people from the various protest movements (ecology, union reform, women’s rights, prison support, etc.) Led by the WUO’s Prairie Fire Organizing Committee, this coalition promised to help everybody fight “Hard Times” by winning new government reforms. Not so coincidentally, the Hard Times coalition would have also incorporated the Third World movements under WUO leadership and have given the Weatherleaders a mass defense organization if they were charged with heavy offenses after surrendering.

The political collapse of anti-imperialism can be seen in the fact that WUO saw the continental national liberation movements as just “minority” component parts of a single, U.S. Empire-wide reform movement under their settler command. Third World radical figures were involved to give cover to the WUO’s attempted co-optation of the Third World movements. An alliance was made between PFOC and Juan Mari Bras’ Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP). Left settler critics of the Hard Times line were rebuked for “racism,” and reminded that they were implicitly criticizing Third World leaders who were involved. WUO said that they were “following Third World leadership.”

The WUO Central Committee issued a political attack on its settler critics in September 1975. Titled “Our Class Stand,” it strongly pushed for co-optive relationships with Third-World people: “White revolutionaries have largely cut themselves off from these relationships. Great opportunities exist at this time, waiting to be seized. But too often white revolutionaries shrink from these openings. sometimes using ‘support for self-determination’ as an excuse.”

In January 1976 almost 3,000 people from all over the continent met in Chicago to attend the founding Hard Times Conference. While it initially appeared impressive, the conference rapidly began self-destructing. Activists from autonomous movements began criticizing the lack of content or any visible purpose other than setting up WUO’s hegemony. Women’s movement criticism was particularly sharp. The main blow came when the Black caucus denounced the Hard Times leadership for racism. Irreconcilable differences appeared. even though most revolutionary New Afrikan organizations had been too opposed or indifferent to the conference to attend.