"You and I were born at this turning point in history; we are witnessing the fulfillment of prophecy. Our present generation is witnessing the end of colonialism, Europeanism, or 'white-ism'... How can Amerika atone for her crimes?... A desegregated theater or lunch counter won't solve our problems. Better jobs won't solve our problems. An integrated cup of coffee isn't sufficient pay for four hundred years of slave labor, and a better job in the white man's factory or position in his business is, at best, only a temporary solution. The only lasting or permanent solution is complete separation on some land that we can call our own."

-- Malcolm X

What shook the Empire in the 1960s was that New Afrikans - and in particular the New Afrikan proletariat - began to assert themselves as a people. This new awareness was manifested in every sphere of life. Welfare mothers asserted that they had rights, and were going to invade welfare offices until the system got off their backs. Olympic athletes used their sports to dramatize the demand for Black Power. Jazz and popular music began to express rebellion. In auto plants New Afrikan workers created revolutionary nationalist alternatives to bourgeois unionism. Emerging national consciousness moved student boycotters in high schools as well as dissenting sailors on aircraft carriers. In the New Afrikan urban rebellions of 1963-1968, millions of people, primarily proletarians, took part in mass anti-colonial outbreaks. And on March 31, 1968, a convention of five hundred nationalists in Detroit, Michigan founded the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika (PG-RNA).

These political changes did not overcome neo-colonial contradictions within the oppressed nation because the petty-bourgeoisie was still in charge. While the New Afrikan proletariat, the grass-roots, had gained awareness of itself as the leading class, it had only begun developing revolutionary science. The masses could not control their own movement. Even the liberation movement remained in the class domination of a sector of the Black petty-bourgeoisie. Relations with the Euro-Amerikan Left were still characterized by false internationalism. This false internationalism, even amidst a national revolutionary advance, betrayed uncertainty not only about the means of liberation but uncertainty about the goal.

The Black radical petty-bourgeoisie was in general half-hearted about independence, and consistently tried to used alliances with the Euro-Amerikan petty-bourgeoisie to substitute for the New Afrikan proletariat. Many petty-bourgeoisie radicals and "cultural nationalists" turned to phony "Marxism-Leninism" in the early 1970s as a cover to merge themselves back into class unity with the petty-bourgeois Euro-Amerikan Left. And Euro-Amerikan radicals continued their intervention and meddling within the New Afrikan nation, although better cosmetized as "solidarity." With the Movement dominated by the Black petty-bourgeoisie, the point of unity of Black united fronts continued to be the demand for U.S. Government reforms.

So the political course of the 1960s New Afrikan liberation Movement became knotted in an apparent paradox: between the growth of anti-colonial consciousness among the masses, on the one hand, and the stalled development of the first New Afrikan guerrillas on the other hand. In 1969-1971, New Afrikan urban guerrillas took to the offensive, attacking the hated police. But despite the general mood of anti-colonialism within the Nation, the first wave of urban guerrillas soon found themselves abandoned by the movement and politically isolated.

This paradox goes to the heart of the two-line struggle, between socialism and neo-colonialism, with the Movement and indeed within the New Afrikan Nation. This two-line struggle is a form of the world-historic two-line struggle between the proletariat (and its ideology) and capitalism (and its ideology).

A PERIOD OF CRISIS

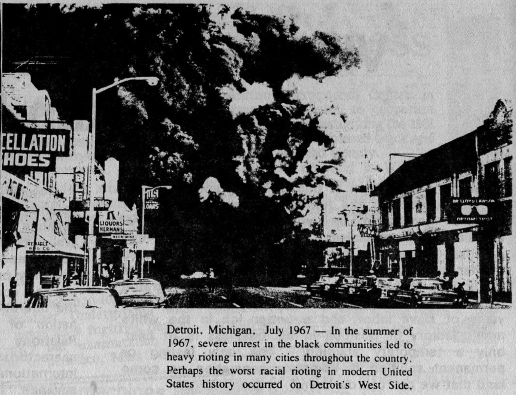

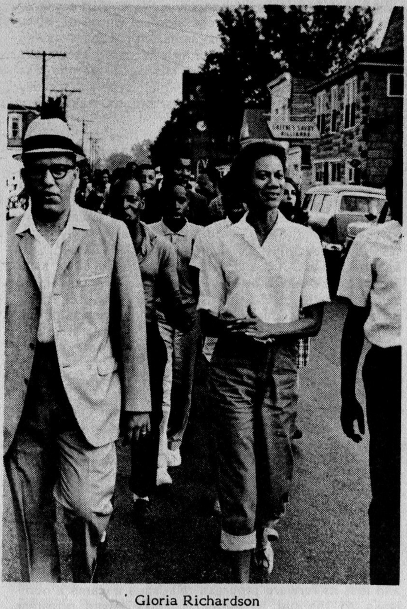

By 1968 the New Afrikan Nation was in the grip of a political transformation, which took the specific form of a generalized uprising against the U.S. colonial oppressor. Between 1963 and 1967-68 mass urban rebellions spread across the continent, growing in number and intensity. From the 1963 outbreaks in Birmingham, Chicago, Philadelphia, Savannah and Cambridge, Maryland to the one hundred and twenty-five rebellions that erupted after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968.

In the transformation within the New Afrikan colony in the late 1960s millions upon millions were awakened to political life and political issues. It was widely agreed that New Afrikan people were not free, and everything was intensely debated and judged on the basis of how it related to aiding liberation - history, sports, religion, criminality, philosophy, war and peace, economic systems, everything.

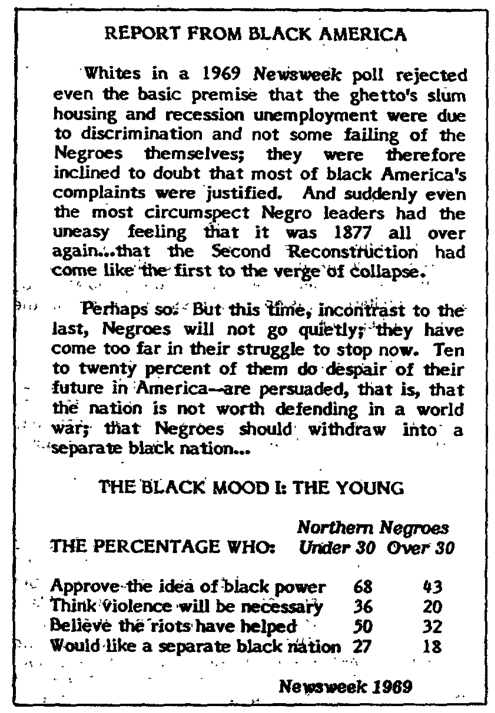

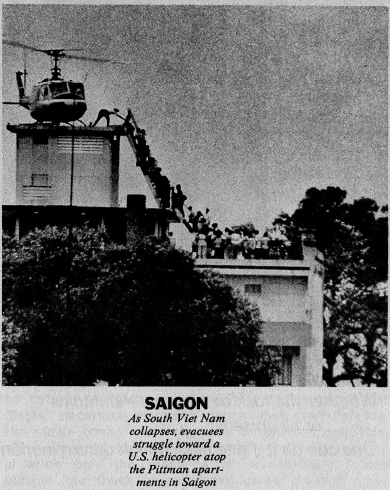

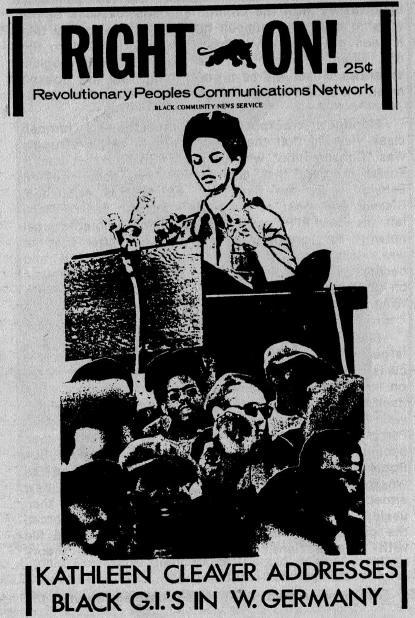

Masses of people rejected loyalty to the U.S. Empire. To talk revolution against the U.S. Government became common and accepted. In the wake of the 1967 rebellions, even U.S. Government interviewers found that 52.8% of Newark "rioters" told them that they opposed any support of the U.S. in foreign wars, irregardless of who the U.S. was fighting. People came to identify more with other Third World oppressed nations than with the U.S. Empire. Increasing political unrest and even outbreaks of rebellion by New Afrikan G.I.s told Washington that their own colonial military was becoming politically unreliable.

The urban rebellions marked both the popular acceptance of anti-colonial violence and the breakdown of the old colonial mechanism of control.

Imperialism had discovered that the old way no longer held. New Afrikan people were "out of control." Pigs could no longer intimidate folks. The "thin blue line" that had patrolled the ghetto had been smashed. To regain control in many areas, the U.S. Empire was forced to re-occupy the ghetto with U.S. Army and National Guard troops, with tanks and jeep-mounted heavy machine guns. Imperialist order could only be reestablished over the hostile population by outright military invasion. Just as in Saigon or the Dominican Republic.

The old system of puppet misleaders had broken down as well. Token government officials, conservative reverends and Civil Rights spokesmen had been thoroughly exposed and brushed aside. The masses had found new unity and self-respect by throwing aside Uncle Toms and by using violence against the oppressor. The old way no longer worked for imperialism.

The crisis was only put down by the Empire's emergency counter-insurgency campaign. Not only by destroying centers of revolutionary organization, but in restructuring their colony through co-opted Black Power politics, breaking up national communities on a physical level, gutting the Peoples' culture, and maneuvering the growing street force into mercenary warlordism. The last is an important indicator of irreversible change.

Imperialism would rather that its colonial subjects stay unarmed and passive. But this can no longer be. The New Afrikan Nation is armed and will never be disarmed. And, just as in old, pre-revolutionary China, the heightened imperialist social dislocation is forcing many into the streets, futureless and desperate. Rather than have New Afrikans turn to combining in revolutionary violence, the authorities have encouraged the growth of warlord gangs. These gangs spread drug pacification, disorganize the community, absorb angry and desperate youth in killing each other, and act as police informers and mercenary agents. Just as in the old China of the 1920s, New Afrika is increasingly a chaotic, armed camp of warlordism. We must see this as dialectical process. Imperialism is brutally creating the raw human material of revolution or reaction.

Back in 1964, Malcolm stood on the front lines and pointed ahead to where the struggle was going: "...A couple of weeks ago in Jacksonville, Florida, a young teen-age Negro was throwing Molotov cocktails. Well, Negroes didn't do this ten years ago. But what you should learn from this is that they are waking up. It was stones yesterday, Molotov cocktails today; it will be hand grenades tomorrow and whatever else is available the next day... There are 22 million African-Americans who are ready to fight for independence right here."(1)

THE REBELLIONS OF 1967-1968

The Empire has tried to cover up the political character and meaning of the New Afrikan urban rebellions by calling them "riots," and associating them with short tempers in hot summer weather. In no cases did the rebellions show random violence. They were "festivals of the oppressed." Everything of the colonial oppressor was attacked by spontaneous group action, from police cars to rip-off stores. Property of the exploiter was liberated, while property of New Afrikan households was untouched. Crowds armed with only rocks and bottles burned police cars and tried to force the occupying colonial army out of New Afrikan areas.

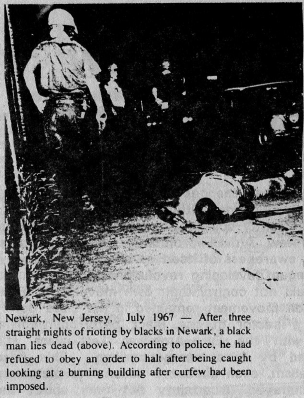

The political character of the confrontation was unintentionally confirmed by President Johnson's emergency National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. Their report, for example, related how the July 1967 Newark, N.J. rebellion began with spontaneous efforts to rescue a taxi cab driver who was being tortured by the police. After people in the Hayes Housing Project witnessed the man being dragged, unable to walk, into the 4th Precinct Station, the spark was lit. Within minutes telephone calls went out to community organizations from the Projects. Cab radios spread the word to New Afrikan workers around the city. Within 30 minutes a large and angry crowd gathered across the street from the station, while a caravan of New Afrikan taxis gathered at City Hall in protest. Civil Rights "leaders" tried to pacify the crowd as police moved the wounded cab driver to a hospital. When Molotov cocktails were thrown at the station, a police charge with nightsticks dispersed the crowd for that night.

The next day anger in the community mounted as word spread. That evening a protest rally was called at the police station. Nationalist leaflets and word of mouth had brought out folks. When the city Human Rights Commission Director tried to cool things by announcing that the Mayor would appoint a committee to "study" the incident and also promote a Black policeman to Captain, booing and shouting began. To shouts of "Black Power" the Uncle Tom was driven away with rocks. The police station was attacked while burning and expropriation of settler businesses began. Thousands of people, too many to be stopped or arrested by greatly-outnumbered police, started taking the groceries, TVs, furniture, medicines and clothing that the oppressed had already paid for a million times over.

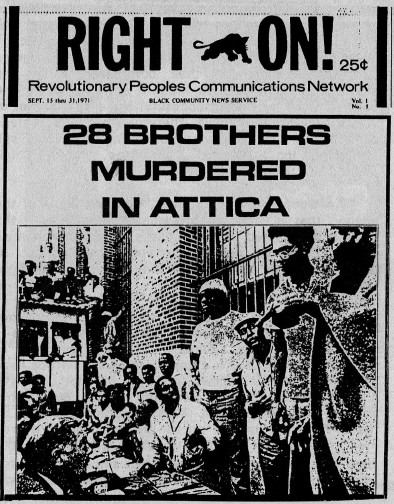

Newark was placed under martial law in the early hours, with nervous State troopers and National Guard reoccupying the New Afrikan areas. Snipers bedeviled the soldiers and police. Afterwards the Newark Police told the Presidential Commission that it had officially confirmed 79 sniping incidents, although only one settler police lieutenant and one fireman had been killed by gunfire. In response the invading forces shot up the New Afrikan areas at will. The housing projects were hosed with heavy machine-gun fire. Washington, D.C. Urban League Assistant Director Horace Morris, who was about to drive away from a visit with his family, saw both his younger brother and his 73-year-old stepfather shot down, the latter fatally. Police had opened fire on folks just standing in front of their apartment building. In total twenty-one New Afrikans were killed in Newark. At night, after curfew had been imposed, National Guard jeeps would cruise around shooting out the windows of stores that had been left alone because they had "Soul Brother" signs on them. The rebellions were simple, oppressed against oppressor.

In interviews and studies of arrest records, the Commission found that those who took an active part in rebellion were typical of the community. In Detroit their interviewers found that 11% of the residents age 15 and older in rebellious neighborhoods admitted to having taken part, with another 20-25% as admitting to having been on the scene. As a whole, the Commission was forced to describe the typical "rioter" as having: "great pride in his race... He is extremely hostile to whites... He is almost equally hostile toward middle-class Negroes. He is substantially better informed about politics than Negroes who were not involved in the riots." In other words, the Government's own study was forced to portray the oppressed people who rocked the Empire as politically motivated and aware. (3)

It is revealing how the Commission contrasted them with their opposite, the Uncle Tom "counter-rioter," who the Government frankly admitted was untypical of the colonial masses in both class and feelings about the Empire:

"The typical counter-rioter, who risked injury and arrest to walk the streets urging rioters to 'cool it,' was an active supporter of existing social institutions. He was, for example, far more likely than either the rioter or the non-involved to feel that this country is worth defending in a major war. His actions and attitudes reflected his substantially greater stake in the social system; he was considerably better educated and more affluent..." (4)

The oppressed nation character of the rebellions was shown by the events around the April 1968 assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. In many ways this was a nodal point, a point where mounting quantitative changes finally result in a qualitative change in the basic nature of the thing. It was no longer a matter of policing demonstrations, of turning off fire hydrants and breaking up angry crowds in one community or another. It was a matter of using crack U.S. Army divisions, National Guard troops and all available police to regain control against a simultaneous mass rebellion that ran from coast-to-coast. King had grown and evolved with the struggle. He was attacking the U.S. war effort; the luster of his name was helping raise world opposition to the U.S. invasion of Vietnam. Even more explosive, his work threatened to link up the New Afrikan struggle with Vietnam.

The failure of Civil Rights had pushed him to reach for new plans. In Memphis, where he gathered national attention for the New Afrikan sanitation workers' strike, King gave notice that he intended to support the New Afrikan proletariat, and not just college students, in their political struggles.

In fact, he planned to unify the oppressed into one new movement - and aim it at direct confrontation with the U.S. Government. His planned Poor Peoples' Campaign was going to recruit tens of thousands of poor people - of all nationalities - and bring them to Washington, D.C. for a mass Gandhian campaign of nonviolent civil disruption. King planned to send thousands of the oppressed in human waves to surround and occupy key U.S. Government offices, including the U.S. Capitol. The masses would camp in downtown D.C. and not leave Washington until their demands were met. As we can well imagine, the Empire was not going to let that happen.

The prospect of having to either openly repress masses of militant demonstrators or let their seat of government be overrun was not an acceptable choice to the imperialists. And what if mass, anti-Government battles spilled over into the Washington ghetto, already smoking with recent rebellion? No, King had to be neutralized. The threat by Empire had been communicated in various ways.

In Memphis, King had announced that for the first time he was going to defy a Federal court order and lead a march in support of the New Afrikan workers' strike. The Memphis City Attorney said in court on April 3rd that if the march took place "someone may even harm Dr. King's life..." (5) King refused to back down, and that night gave his famous sermon foreseeing his death: "I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the promised land. So I'm happy tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man." The next afternoon, April 4, 1968, he was assassinated, as Malcolm X had been before him.

His assassination was a nodal point, brutally cutting off any remaining life in the old Movement. After Rev. King, there was no other major Civil Rights leader willing to lead the masses against the center of oppression, the U.S. Government. For that matter, the soft-nosed bullet from a Remington 30.06 rifle also blew away illusions about nonviolent integration, about "redeeming" White Amerika, about New Afrikans and settlers healing their differences and freely mingling together in a reformed amerikkka. The assassination had also underlined the fact that imperialism would not willingly tolerate anyone organizing and leading the New Afrikan Nation. No unprotected national leadership or organization that was dangerous to the Empire would be permitted to survive.

Within hours the rebellions broke out anew in some 125 cities across the Empire. Again buildings burned and police were attacked. 65,000 U.S. Army troops and National Guardsmen were needed to reinforce state and local police in containing the outbreaks. Fires burned within sight of the U.S. Capitol building; smoke hung over the city. The White House was so worried that U.S. Marine machine-gun teams were posted on the Capitol steps and select military units were placed on alert, ready to rush to Washington to defend the Empire's headquarters.

Even within these select military units the anti-colonial crisis had a political effect. The 6th Cavalry Regiment (Mechanized) at Ft. Meade, Maryland, which spent that year on-and-off alert for "riot control" intervention in Washington, was polarized along national lines. Settler officers had secret orders to watch for conspiracies among their New Afrikan troops. By the Summer hand-picked MP units patrolled the fort after 11:30 pm with orders to detain any New Afrikan G.I.s on the streets in groups of more than two. New Afrikan soldiers were discussing refusing to follow orders. On the other side, many settler officers and men were eager to go to war against the New Afrikan colony. One Lieutenant openly said: "If I can't get to 'Nam and kill some gooks then maybe I'll at least be lucky enough to get a couple coons."

At Ft. Campbell, Kentucky, New Afrikan G.I.s staged a rebellion of their own on the nights of April 10-11th, as soon as the base stood down from being on 24 hour "riot control" alert after King's death. Fighting took place with known racists all over the post, an MP jeep was destroyed, and the entire base had to be placed under curfew. (6) In Vietnam, New Afrikan G.I.s staged memorials and political meetings as the word raced around: "They killed Martin!" Again, we can see that the fundamental political contradictions between the New Afrikan oppressed nation and the U.S. Empire took on many forms, and did pervade every sphere of life.

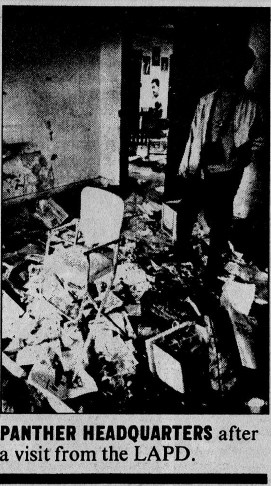

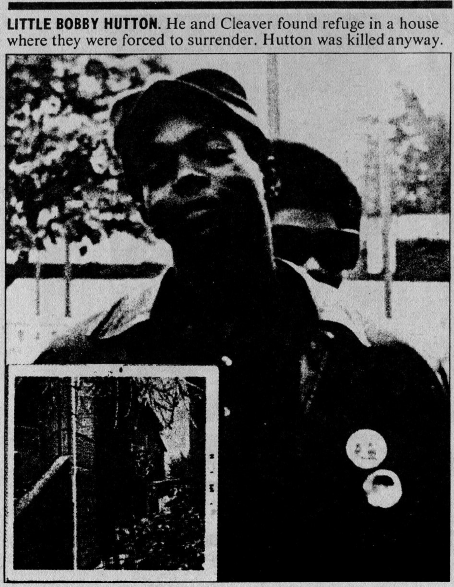

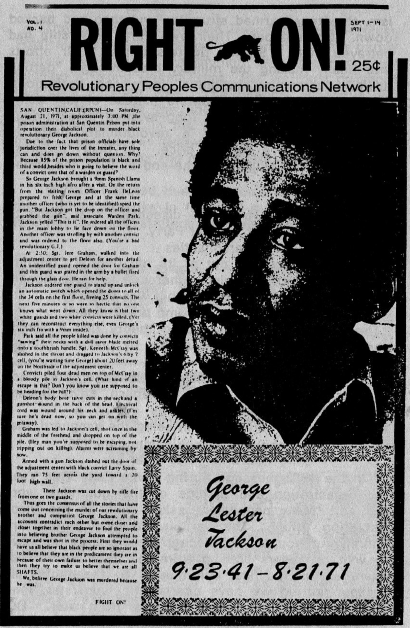

New Afrikan high schools and even grammar schools emptied. Countless local marches and demonstrations took place. In Washington, for example, one hundred high school students led by SNCC's Black Antiwar Antidraft Union marched out to Howard University, picking up two hundred more youth on the way. There they joined 1,000 Howard students in an angry rally. The U.S. flag was torn down from the University flagpole, and the New Afrikan green, black and red flag run up in its place to cheering. (7) There were confrontations everywhere. In Oakland the police raided the Black Panther Party. After surrendering to the police young Bobby Hutton, surrounded and blind from tear-gas, was shot down in cold blood.

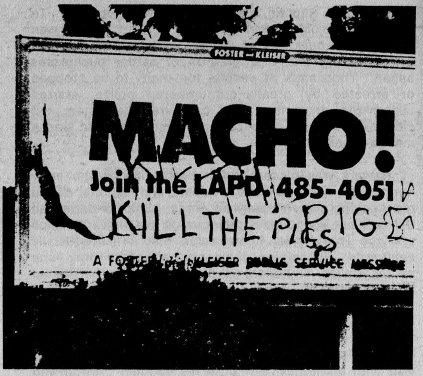

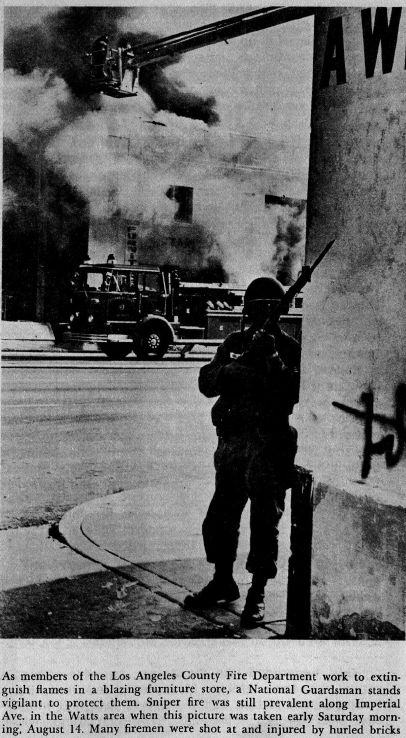

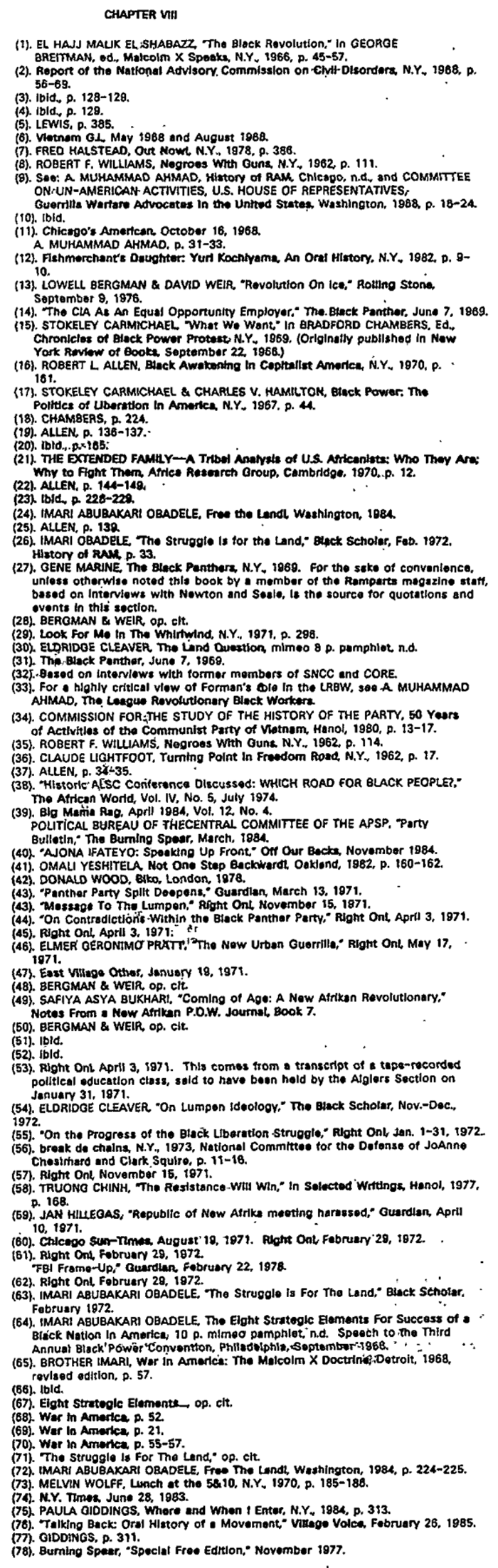

(As members of the Los Angeles County Fire Department work to extinguish flames in a blazing furniture store, a National Guardsman stands vigilant to protect them. Sniper fire was still prevalent along Imperial Ave. in the Watts area when this picture was taken early Saturday morning, August 14. Many firemen were shot at and injured by hurled bricks)

Those April 1968 rebellions were completely political, and could hardly be explained away as bad tempers due to hot weather. They were a united mass response of the New Afrikan grass-roots to a political assassination. Martin Luther King, Jr. was not the only or even the main political leader, but he was both a leader and a symbol to the world of the New Afrikan anti-colonial struggle. His death was taken to heart by millions. His assassination was understood as a calculated blow aimed at the entire liberation struggle. And the masses laid the primary blame not on a "lone gunman," not even on a Government conspiracy, but on the U.S. oppressor nation as a whole. "They killed Martin!" the word ran.

BLACK POWER MOVEMENT - REVOLUTION OR PIECE OF THE ACTION

When the shout "Black Power" first came to white attention across that Mississippi summer of 1966, an incredulous White Amerika took it like a life-threatening blow to the body. Black Power represented to the masses an attitude of bitterness, separatism, and uncompromising militancy. It spoke the language of the masses. Black Power leaders sneered at Civil Rights integrationism. They urged New Afrikans people to arm themselves. Yet, only two years later U.S. imperialism was financing some Black Power organizing, leading petty-bourgeois Black Power figures were collaborating with the police, and President Richard Nixon had promoted himself as the big boss of a co-opted Black Power Movement.

This underlined the on-going, two-line struggle within the New Afrikan Movement, and how Black Power contained two political trends: one anti-imperialist and one pro-imperialist. The first trend, which was reflected in the mass approval for the slogan, interpreted Black Power to stand for self-determination, for militant separation from the oppressor society and its culture. The second trend denied that Black Power had anything to do with that. That second trend believed that revolution by the masses should be merely a threat, to be exploited by the colonial petty-bourgeoisie. In their class view the goal of Black Power was to finally integrate into the U.S. oppressor nation, finally getting "a piece of the action."

There were two Black Powers - one grass-roots and one petty-bourgeois, one revolutionary nationalist and one neo-colonial. It is important to remember that the second, petty bourgeois trend tried to blur the political differences, to sound as militant and nationalistic as possible. The grass-roots trend of Black Power led into the revolutionary nationalist movement. This was the political heritage carried on by Malcolm X, who had helped create Black Power with his program in the 1950s of self-pride, self-reliance, self-defense, and independence from the U.S. oppressor nation. This trend helped create the Black Panther party, the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika, the League of Black Revolutionary Workers, and the Black Liberation Army. It led folks from armed self-defense to the concept of revolutionary armed struggle. The second, petty-bourgeois trend led to foundation grants, government property pimps, the dead-end of electing Black bourgeois politicians, and the liquidation of mass struggle.

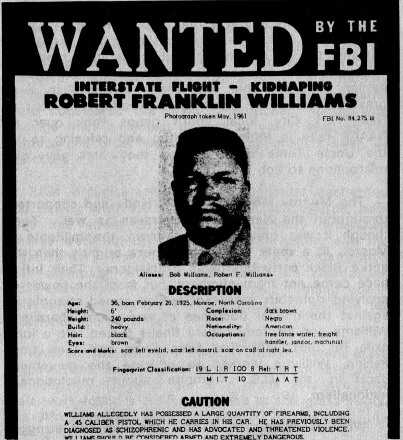

The grass-roots wanted revolutionary nationalist leadership. This was proven not only by Malcolm's towering reputation, but by their positive response to organizing efforts. There has always been a revolutionary current, sometimes on the surface and sometimes hidden, within the New Afrikan Nation. Even while the 1955-56 Montgomery Bus Boycott was bringing the nonviolent Civil Rights Movement into the world's eye, the armed self-defense movement led by Robert Williams in the small town of Monroe, North Carolina, was stirring up the New Afrikan masses.

Rob Williams was discharged from the Marines in 1955, and returned to his home town of Monroe, N.C. in Union County. Within three years both he and the New Afrikan struggle in that small town would be internationally known as heralding a new season of struggle. The local Klan had threated the small Union County NAACP chapter, which was the only local civil rights group. So the petty-bourgeois NAACP leaders wanted to dissolve the chapter in order to save themselves. When Williams, a new member, objected, they voted him in as President and then they resigned. Only Dr. Albert Perry, an older physician, agreed with Williams. Together they rebuilt the chapter by going to the grass-roots, always stressing the need for armed self-defense. (8)

At first, as Williams said, "when I started talking about self-defense, I would walk through the streets and many of my Black neighbors would walk away to avoid me." With two years of patient organizing, oriented toward the proletariat instead of the "elite," they had recruited an impressive number of New Afrikan working people - domestics, day laborers, grandmothers and teen gang-bangers. To get inexpensive U.S. Army surplus rifles Williams formed a branch of the National Rifle Association. Veterans were recruited. By 1957 the Monroe self-defense guard got its baptism of fire, driving off a Klan assault on Dr. Perry's house. Day and night New Afrikans kept an eye out for settler intruders, phoning reports into a self-defense headquarters which would alert armed units into full readiness.

While the Union County NAACP fought with lawsuits and picket lines, and tried to open swimming pools, the library and other public facilities to New Afrikans, it always made the official Civil Rights movement uneasy. People recognized that the Monroe organization was politically different, the start of a more militant movement. Williams, Dr. Perry, Mae Mallory and the other Monroe activists were forced to fight for support within the Civil Rights Movement, but increasingly had to operate on their own, in advance of the times, the small Monroe Movement pursued propaganda campaigns and alliances on an international scale. Although most of the known Monroe activists had been fired from their jobs, the national Civil Rights leadership saw to it that no aid was given to the Monroe Movement. The besieged New Afrikan community there was literally going hungry. We can see the emerging two-line struggle, in which the Monroe Movement had to hold out under attacks not only from the Klan and State Police, but also from the NAACP and SCLC. Williams and his co-workers had to be their own movement - to raise funds in the North, publish their own political journal, make their own secret arrangements to truck in arms, food and medicine at night, and make their own alliances with sympathizers from other nations.

In late 1958 the Monroe Movement became world-famous, partly because of the so-called "Kissing Case." It began when a young Euro-Amerikan girl kissed a nine-year-old New Afrikan boy on the cheek as a greeting. When the girl's parents found out about it, they went to the Monroe police. The nine-year-old boy and a companion were arrested and eventually sentenced to 14 years in prison for rape. Unable at first to free the children, the Monroe Movement struggled to wake people up about the case. Newspapers in Europe and then Afrika started writing about it. Soon it became an international scandal exposing U.S. colonial injustice. Enraged crowds stoned U.S. Embassies. Finally the White House had to intervene to release the young children and end the publicity.

Williams and the Monroe Movement had to fight the "Kissing Case" without any support from the National NAACP, which was trying to isolate or silence militants any way they could. Finally, in 1959, the National NAACP announced that it had suspended Williams for six months for publicly stating that New Afrikan men in Monroe would defend women against settler attacks. This only made Williams an even greater hero to the grass-roots. During one visit to New York City, local youth gangs took over an NAACP rally in Harlem, shouting and refusing to let the Uncle Toms speak unless they first gave the microphone to Rob Williams.

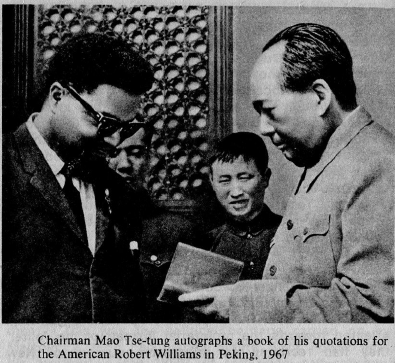

The Monroe Movement had friends and supporters throughout the Nation, and overseas as well. Even though it was only one small town, the militants in Monroe lit a spark that burned more brightly than the entire Black petty-bourgeois officialdom. Their influence came not from numbers, but from the power of applying righteous ideas - of raising armed struggle as against the official doctrines of nonviolent liberalism. Williams and his family were finally forced into a long exile in 1961. At first from Cuba and then from Peking, Williams worked to educate the movement back in the U.S. Empire about revolutionary nationalism.

What is significant is how the two-line struggle emerged within the early Southern Civil Rights Movement, even in the 1950s. Turning to the New Afrikan proletariat with a correct line of armed struggle produced lessons that from a small beginning spread throughout the New Afrikan Nation. This prepared the way for the new stage of revolutionary consciousness that made up one trend within Black Power.

In exile Robert Williams was to become international Chairman of RAM, the Revolutionary Action Movement, the first of the three major New Afrikan revolutionary organizations of the 1960s. (9) Although seldom mentioned today, RAM was labeled as the most dangerous New Afrikan folks in Amerika back in the mid-1960s. Congressional investigations were held about RAM, and police denounced RAM in press conferences. Nothing, the public was told by authorities, was too murderous for RAM to attempt. RAM members were arrested for an alleged plot to blow up the Statue of Liberty. RAM members were charged in an alleged plot to correct the No. 1 and No. 2 Uncle Toms, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and Whitney Young of the Urban League. RAM was even charged with a conspiracy to wipe out thousands of Philadelphia police and city officials, by feeding them cyanide-poisoned coffee and sandwiches from a street canteen after luring them to a staged "ghetto riot." As we know, when the imperialists put out lots of smoke there's usually some fire involved.

RAM was a serious attempt that failed to build an armed national revolutionary organization, a New Afrikan version of the Algerian FLN or the July 26th Movement of Cuba that didn't sustain itself or survive. It never was "legal"; it never was a Civil Rights organization. It was the result of the new message of Williams and Malcolm X, trying to put their insights into practice. From the start they aimed at armed socialist revolution. RAM developed into a broad network of revolutionary nationalists, a semi-public organization with clandestine cells and full-time traveling organizers. No one could have any doubts about what RAM was trying to do. As their journal, Black America, said in 1964:

"... The Revolution will 'strike by night and spare none.' Mass riots will occur in the day with the Afro Americans blocking traffic, burning buildings, etc. Thousands of Afro Americans will be in the street fighting; for they will know that this is it. The cry will be 'It's On!' This will be the Afro American's battle for human survival. Thousands of our people will get shot down, but thousands more will be there to fight on. The Black revolution will use sabotage in the cities - knocking out the electrical power first, then transportation, and guerrilla warfare in the countryside in the South. With the cities powerless, the oppressor will be helpless." (10)

RAM had its beginnings among New Afrikan college students in Ohio. The news in 1961 of Robert Williams' flight into exile had been a catalyst, bringing a small group together to discuss how a Black revolutionary movement could be built. These students already had varied political experiences between them - of student sit-ins in the South, fighting for activist student government at Black colleges, going to S.D.S. Conferences, studying with white Trotskyist groups, being in the Nation of Islam, and so on. By the Summer of 1962 those still struggling together had decided to try starting such a New Afrikan revolutionary movement in one city, Philadelphia, as a test. Don Freeman, Wanda Marshall and Max Stanford were leading activists in the student network that would become RAM.

Like Williams, the young revolutionaries began by working within the local NAACP. They soon discovered that hundreds and sometimes thousands of street youth could be attracted to militant direct action. By 1963 street demonstrations in North Philadelphia, blocking construction sites where New Afrikans. RAM had developed a definite perspective which it spread to other cities. RAM cadre worked within the existing civil rights organizations, pushing militant actions and raising the need for armed self-defense, as part of a strategy of turning the Civil Rights Movement into a Black Revolutionary Movement. The street force or lumpenproletariat were considered the main revolutionary force, with teenage men (as young as age 14 years) seen as the fighters and older working-class nationalists seen as the cadre.

RAM organizers used direct agitation, leafleting and talking with the street force in schoolyards, pool halls and street corners. Revolutionary nationalist classes were set up, teaching Afrikan history and the organization's line. The national RAM organization that eventually emerged was based on clandestine local cells, with the central leadership forming coalitions with existing Black organizations to prepare for a national liberation front.

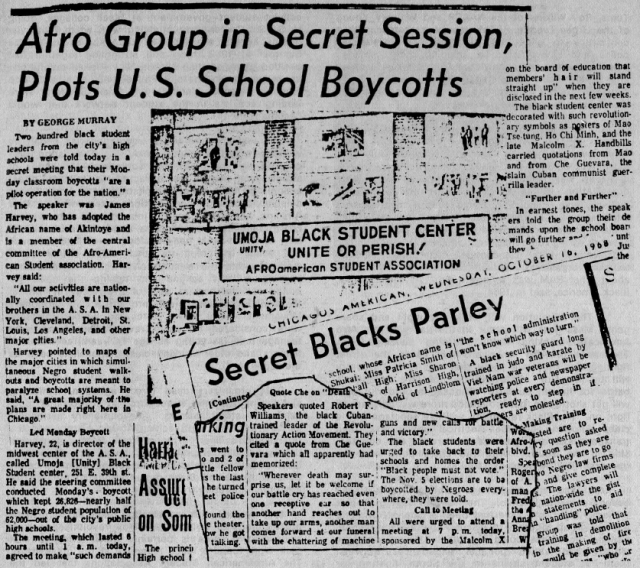

RAM worked with and through many different mass organizations in trying to develop revolutionary consciousness. There is certainly much evidence that their work found a ready response at the grass-roots. The Afroamerican Student Associations that led the fight for New Afrikan history in the public schools of Philadelphia, Cleveland, Chicago, New York, and other cities, were guided by RAM. In Chicago, for example, RAM cadre, working behind-the-scenes at their 39th St UMOJA Black Student Center, coordinated the October 1968 high school strike that brought out half the city's New Afrikan high school students. There the city Afroamerican Student Association united recognized student leaders from over twenty New Afrikan high schools. RAM classes discussed guerrilla warfare and socialism with young activists. (11)

By 1966 RAM was trying to build mass New Afrikan political parties in cooperation with SNCC and other radical or nationalist groups. At that time SNCC had formed the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) in rural Alabama, as a Black Power organizing project. Using the black panther as its symbol, the organization was an all-New Afrikan electoral alternative to the regular Democratic Party, doing voter registration gun in hand and running candidates for county offices.

The concept of a militant New Afrikan political party had stirred up much interest across the country. So RAM got SNCC's permission to use the black panther symbol and start Black Panther Parties in the Northern New Afrikan ghettoes. Local Black Panther Party organizations were set up in New York, Cleveland, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and other cities. RAM wanted to use these parties as New Afrikan united fronts, eventually so commanding the day-to-day politics of the community that the oppressor Democratic and Republican Parties would be forced out of the New Afrikan areas.

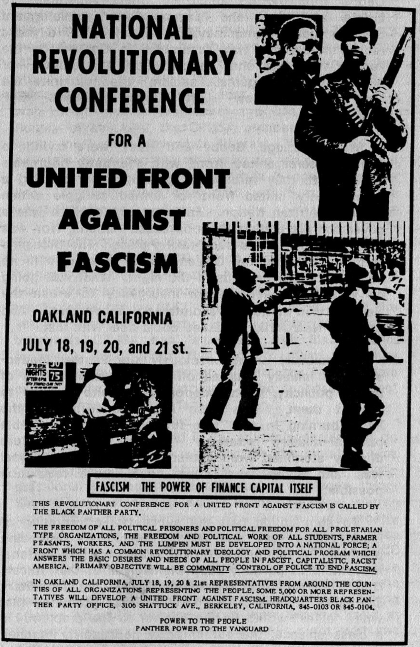

There were at one time three militant Black parties which used the black panther symbol, with two of them also both using the name "Black Panther Party." For in 1966 two nationalist students at Oakland, California's Merritt College - Huey Newton and Bobby Seale - had formed the para-military "Black Panther Party for Self-Defense." It is this party, with its now-famous uniform of black beret and leather jacket, that is best known today.

The three parties were not only separate organizations, but were very different. SNCC's Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) was primarily a Civil Rights electoral party, whose thrust was to elect Black officials in county government offices such as clerk and sheriff. In rural Alabama its base was primarily radicalized New Afrikan workers and students. The Oakland, California Newton-Seale Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was a public, para-military vanguard, which sought to mobilize the New Afrikan lumpen under their leadership around armed self-defense of the community. Despite the identical name, RAM's party was different in program, leadership and class composition. It was intended as a multi-class front. Different militant groups with different leaders would hopefully work together within the party. The aim was to unite the New Afrikan nation around one political voice, which would be so strong that it could dictate which Black candidates got elected to local offices. Armed activity under RAM's perspective could not be public, and would be kept separate from the public formation. In any case, RAM's ambitious party did not survive, which permitted Newton and Seale to drop the tag phrase "for Self-Defense" from their name, and become known simply as the Black Panther Party.

While RAM's Black Panther Parties did not take root in some cities, in New York the party quickly developed into real unity. Not only RAM cadre and SNCC organizers, but Amiri Baraka's Harlem Freedom School, Jesse Gray's tenants' anti-slum movement, New Afrikan socialists such as Bill Epton (famed for his role in the 1964 Harlem rebellion), and many other nationalists joined in. The N.Y. Black Panther Party as a militant united front led marches against police brutality, organized youth to help take over and fix up slum buildings, ran classes on Afrikan history and other political topics, and was forming groups within each ghetto public school. Asian-American activist Yuri Kochiyama, who was part of the Harlem Freedom School at the time, recalls:

"The Party had a broad outreach; it was still growing. At the time there was only this one, large, militant, grass-roots organization. They were trying to get Black principals in Harlem and in Bedford-Stuyvesant. There had been demonstrations at quite a few schools." (12)

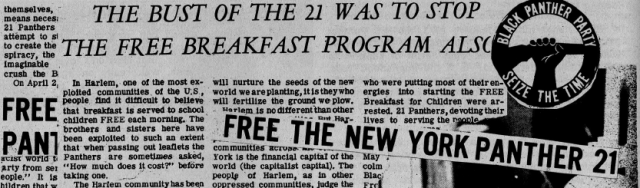

But RAM organizing was smashed by U.S. counter-insurgency. On June 21, 1967, the N.Y.P.D.'s Bureau of Special Services (B.O.S.S. - the political police) arrested seventeen RAM members for an alleged conspiracy to assassinate NAACP Director Roy Wilkins and Urban League Director Whitney Young. The police claimed that their raids had found illegal weapons, plastic cans full of gasoline and 275 packets of heroin. This was the Queens 17 defense case, a forerunner of the Panther 21 case. Main FBI-N.Y.P.D. targets were Adekouya Akinwole (sn Herman Ferguson), a nationalist assistant principal of a Brooklyn public school, and Muhammad Ahmad (sn Max Stanford), the Field Chairman of RAM. Three months later, on September 27, 1967, Philadelphia police arrested more RAM cadre for another alleged conspiracy, this time to supposedly kill thousands of police and city officials with poisoned coffee and sandwiches. That was just the tip of the iceberg, as many RAM members were arrested during rebellions and in other confrontations.

The suppression of RAM became a textbook case for the FBI. RAM cadre were taken out of action that Summer. George C. Moore, head of the FBI Racial Intelligence Section, cited the RAM case in his February 29, 1968 internal memo on COINTELPRO strategy against the BPP: "The Philadelphia office (of the FBI) alerted local police who then put RAM members under close scrutiny. They were arrested on every possible charge until they could no longer make bail. As a result, RAM leaders spent most of the Summer in jail..." (13)

With many leading cadre in jail or tied up in trials, and others fugitives, with paranoia over police infiltrators mounting, RAM floundered. Like Malcolm's OAAU, like Robert Williams' Union County, N.C. NAACP chapter, RAM had not solved the task of revolutionary infra-structure, of spreading a network of organizing among masses even while the imperialist counter-insurgency was raging. Or as Atiba Shanna has put it, organizing "in the free-fire zone."

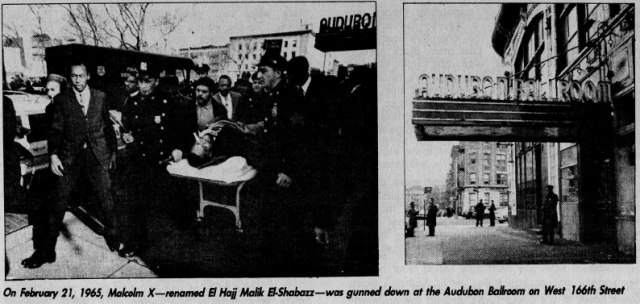

RAM was advanced in its time precisely because from the beginning it was oriented toward leading a national liberation war. It was also not fully developed since it was a pioneer, the first wave. It was a serious attempt that failed, unable to advance its practical work beyond a certain point because its basic politics had not yet developed past that point. Its Field Chairman and main theoretician, A. Muhammad Ahmad (sn Max Stanford) had written: "RAM was plagued with the problem of translating theory into practice, that is, developing a day-to-day style of work (mass line) related to the objective materialist reality in the United States. Like most Black revolutionary organizations, RAM was not able to deal successfully with protracted struggle." We recall that Malcolm, the most important strategist of the 1960s, had been assassinated in 1965. Many other OAAU (Organization of Afro-American Unity) members had been assassinated or imprisoned, and the organization itself died before it had a chance to put its planned mass programs into effect.

There can be no doubt that the first wave of New Afrikan revolutionaries in the 1960s accomplished a historic task, and started the movement in the right direction. But due to the incomplete political development of the new movement, New Afrikan revolutionaries were unable to build organizations that could withstand the political police.

So despite the hunger for revolutionary nationalist answers down in the grass-roots, among the proletariat, there was a profound leadership vacuum during the anti-colonial crisis in the New Afrikan Nation. The masses had exposed and pushed aside the traditional puppet mis-leaders - conservative reverends, token Black Government officials, etc. The nonviolent Civil Rights integrationists had been made irrelevant by the mass anti-colonial rebellions. And the new revolutionary current had been neutralized before it had developed by their own political weaknesses and the imperialist counter-insurgency which took full advantage of them.

THE CO-OPTATION OF BLACK POWER

It was only in such a leadership vacuum that the Black Power Movement could have been co-opted so easily by settler imperialism and its Black allies. As a slogan "Black Power" spread like wildfire among the masses, who wanted something more militant than Civil Rights. But its vagueness (unlike slogans such as "Free the Land") concealed within it the fact that there were two very different meanings to Black Power. To the young militants, to the angry people in the streets, Black Power meant rejecting White Amerika, seizing some kind of Black independence from the oppressor. But to the leading petty-bourgeois forces of the Black Power Movement the goal was only equality with all other U.S. citizens.

Separation from the oppressor was not seen as a step in moving toward national independence, but only as a tactical regroupment so that Blacks as a supposed "ethnic group" could bargain for their "piece of the action" just like the Irish, the Jews, the WASPs and other U.S. "ethnic groups." The Empire tries to define oppressed nations as "ethnic groups" so as to deny their existence as nations. This blurs New Afrikans, Puerto Ricans, etc. in with Italian-Amerikans, Irish-Amerikans, etc., just as earlier the oppressed were only categorized as "races" in order to hide their national status.

The stated goal of neo-colonial Black Power ideologists was actually integration with White Amerika, only repackaged in a nationalist-sounding way in order to appease the anger of the grass-roots. Thus, as an organized movement, Black Power became reactionary very quickly. As early as 1969, The Black Panther, newspaper of the Oakland-based BPP, warned about this:

"Black Power has come a long way since that night in 1966 when Stokeley Carmichael made it the battle cry of the Mississippi March Against Fear. For a time it was a slogan that struck dread into the heart of white America - an indication that the ante of the Black man's demands had been raised to a point where the whole society would have to be reoriented if they were to be met. But Black Power hardly seems a revolutionary slogan today. It has been refined and domesticated...by Richard Nixon, seemingly the most unlikely of men... The President has indicated since assuming office that he sees nothing dangerous in the upsurge of a Black militancy, provided that it seeks a traditional kind of ethnic mobility as its end, even if it wears Afro costumes and preaches a fiery race pride while it sets up businesses and replaces white capitalists as our society's most visible contact with the ghetto...

"He has made a surprising alliance with certain forces of Black militancy. This may seem audacious, even dangerous, like playing with the fires of a revolutionary Black consciousness. But it is actually a time-tested technique. The Nixon Administration's encouragement of cultural nationalism and its paternal interest in Black capitalism are little more than an updating and transposition into a domestic setting of a pattern established years before by U.S. power abroad. Although the State Department, the U.S. Information Agency, the Ford Foundation and hosts of other organizations were involved, it was primarily the Central Intelligence Agency which discovered the way to deal with militant Blackness..." (14)

It is important to see that petty-bourgeois Black Power as a philosophy and a program was a desperate effort to make integration work for the Black petty-bourgeoisie. Even some radical initiators of Black Power made that plain. In his historic September 1966 article "What We Want," Stokeley Carmichael of SNCC said that the main strategy was uniting the Black community to elect Black politicians into office. This, Carmichael claimed, would make Blacks so "equal" to whites that integration would become real:

"...Politically, Black Power means what is has always meant to SNCC: the coming-together of Black people to elect representatives and to force those representatives to speak to their needs. It does not mean merely putting Black faces in office... Integration, moreover, speaks to the problem of Blackness in a despicable way. As a goal, it has been based on complete acceptance of the face that in order to have a decent house or education, Blacks must move into a white neighborhood or send their children to a white school. This reinforces, among both Black and white, the idea that 'white' is automatically better and 'Black' is by definition inferior... Such situations will not change until Black people have power - to control their own school boards, in this case. Then Negroes become equal in a way that means something, and integration ceases to be a one-way street. Then integration doesn't mean draining skills and energies from the ghetto into white neighborhoods; then it can mean white people moving from Beverly Hills into Watts, white people joining the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. Then integration becomes relevant." (15)

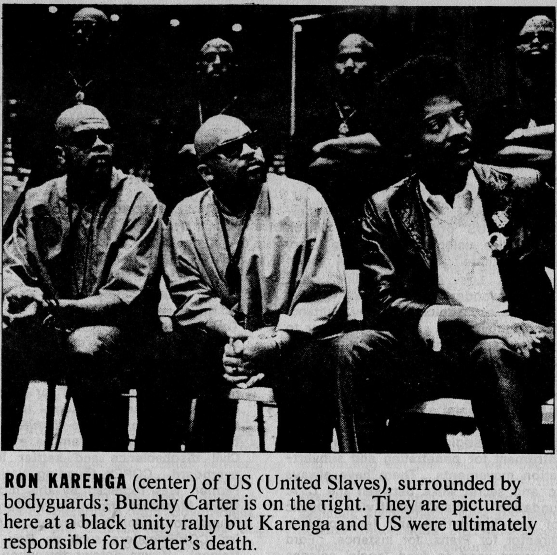

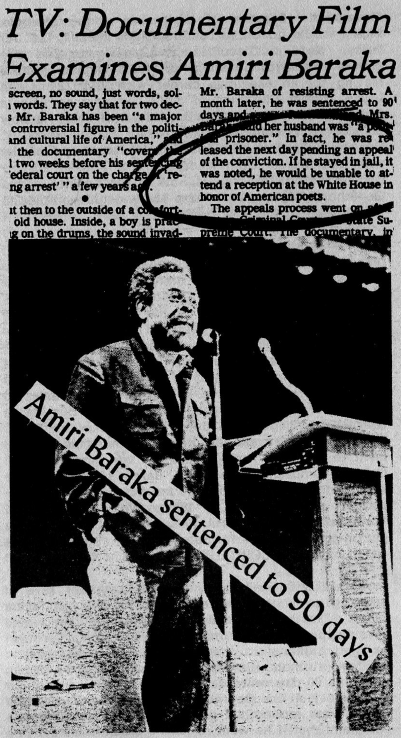

Carmichael's unreal and misleading vision of "relevant" integration was not just naive. These views were put together, we must remember, a year after Malcolm X was assassinated, four years after Robert Williams was forced to flee into exile, years after the call for national liberation had been raised within the movement. While some militants who raised the slogan were trying to push the struggle forward, the neo-colonial political framework was in conflict with their own desires. The Stokeley Carmichaels and Ron Karengas and Amiri Barakas saw the U.S. oppressor nation as the only "real," legitimate nation. They didn't see New Afrikan people as an oppressed Nation, but only as an "ethnic minority" inside the U.S. oppressor nation. Ron Karenga was a former graduate student at the University of California. After the Watts Rebellion in 1964 he formed "U.S." (United Slaves), the most influential "cultural nationalist" organization of the 1960s. His protégé was Amiri Baraka (sn Leroi James), the Black poet and playwright. Baraka became the leader of the Black Power Movement in Newark, N.J. and the Congress of Afrikan Peoples (CAP). Both men made the journey to pseudo-nationalism and then back to liberal integrationism/assimilationism via the cover of phony "Marxism-Leninism." As someone remarked: "Every year they got a new philosophy, but they always got a foundation grant."

For that reason the petty-bourgeois Black Power theorists all saw peaceful integration into White Amerika as the final goal. Among the most explicit was Rev. Nathan Wright, chairman of the 1967 Newark Black Power Conference (which was the first one) and later head of the Black Studies Dept. at San Francisco State University: "Black Power in terms of self-development means we want to fish as all Americans should do together in the main stream of American life." (16)

In their 1967 book on Black Power, Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton said that Black separatism was only a tactic to gain bargaining power for integration into Amerika: "The concept of Black Power rests on a fundamental premise: Before a group can enter the open society, it must first close ranks. By this we mean that group solidarity is necessary before a group can operate effectively from a bargaining position of strength in a pluralistic society." (17) It's revealing that SNCC's Stokely Carmichael, who at that point was a self-proclaimed "socialist" and a partisan of Third-World liberation wars, would explain the U.S. oppressor nation as "open" and "pluralistic." David Rockefeller and Richard Nixon would have agreed with that. The obvious confusion existed between roundly denouncing the U.S. as evil, imperialist, oppressor, colonialist, and so forth - and then putting out a strategy based on the assumption that this oppressor society was "open" for you. This confusion had its roots in the class role of the New Afrikan colonial petty-bourgeoisie.

Pseudo-nationalism was the sudden rage. Audiences at Black Power conferences would be treated to the full spectacle when Ron Karenga spoke. Karenga had been written up in Life and other bourgeois media as the most extreme and dangerous. The sight of the Simbas, US's para-military guards, drilling with arms for new photographers, thrilled White Amerika. Karenga would be preceded on stage by an aide and his guards, all in US "uniform" (shaved head for the leaders, mustache, shades, dashiki-like shirt of his design). His aide would order the audience to rise and chant "All Power to the Black Man" over and over. Karenga himself would then denounce integration while dropping hints about their main "weapon" for liberation - at the end of the rap he would reveal that the main "weapon" was only voting for Black candidates in elections! So while even veteran Black journalists referred to Karenga as an "extremist Black nationalist," only the outer packaging was in any way different. (18) "Cultural nationalism" was a phony nationalism that opposed the independence of the New Afrikan Nation. Instead, it argued that militant talk, different clothing and getting involved in U.S. elections would allow New Afrikans to find a satisfactory place for themselves within White Amerika.

Co-opted Black Power made possible an improved relationship between the colonial petty-bourgeoisie and their masters. This was not immediately apparent to the grass-roots. The New Afrikan families in Alabama who turned out to picket at courthouses, proudly carrying Black Power signs ("Move on over, or we'll move on over you!") were charged up by the air of defiant assertiveness and "race pride." Washington street youth attending early "Black history" courses and organizing their friends took Black Power to mean nationalist opposition to the oppressor.

But it was precisely this seemingly militant, seemingly nationalist tone of voice, that made Black Power so useful to the Empire. When Black Power leaders spoke of the vision of Black people controlling all institutions of their own communities, it seemed to give voice to the anti-colonial urban rebellions. Black Power's angry image allowed the colonial petty-bourgeoisie, temporarily shaken up and out by the growing mass consciousness, to reassert its leadership over the New Afrikan Nation. And therefore to have something to sell their colonial masters in return for a few pieces of silver. What they had to sell was their own people.

Many petty-bourgeois Black Power leaders began working with the police. In Newark, Amiri Baraka had formed the United Brothers, a united front to elect more Black politicians to city government. Their goal was to elect a Black mayor. Baraka understood bourgeois politics well enough to understand that he had to make deals with the local settlers and the police. In April 1958 the United Brothers worked with the Newark police to "cool" the rebellion which broke out after Martin Luther King's assassination. Baraka publicly disassociated himself from the rebellion. On April 12, 1968 he held a joint press conference with Newark Police Captain Charles Kinney and Anthony Imperiale, the leader of the local armed white racist organization. (19) Baraka denounced the rebellions as just confused New Afrikans being manipulated by unnamed white radicals. He also made it clear that his Newark Black Power Movement and the armed white supremacists were cooperating. Pig captain Kinney jumped in to add that New Afrikan rebellion was only a conspiracy led by white S.D.S. students. That was how the most prominent petty-bourgeois Black Power leader reacted to the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, Baraka's close associate Ron Karenga had his "US" organization also out on the streets with the police, using their influence to try and stop the rebellion there. Karenga had a secret planning meeting with Los Angeles Police Chief Thomas Reddin. No wonder that the Wall Street Journal praised Karenga as: "typical of many militants who talk looting and burning but actually are eager to gather influence for quiet bargaining with the predominantly white power structure." (20)

We can see how very useful that kind of co-opted Black Power was to the colonial authorities. Imperialism had quickly realized that. The C.I.A. had previously arranged for the prestigious Ford Foundation to be their main instrument for penetrating and subverting Afrikan liberation movements. There have always been both public and secret links between the C.I.A. and the Ford Foundation. Richard Bissell was a public staff member of the foundation and less publicly C.I.A. Deputy Director for Plans, for instance. Ford Foundation grants were used to fund "social science research" (i.e. intelligence operations), buy off opportunistic Afrikans, and cover up for U.S. subversion of popular movements. (21) As The Black Panther said, this operation was simply expanded in 1966 to include the domestic New Afrikan communities. This new effort was overseen by none other than Ford Foundation President McGeorge Bundy, who as former National Security Advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson had run the National Security Council and had helped plan the U.S. invasion of Vietnam. "Charity begins at home."

The Ford Foundation singled out Cleveland as their test case in pacification. In 1966 New Afrikan rebellion there shook the city. Ford Foundation President Bundy told the press in 1967 that "it was predictions of new violence in the city that led to our first staff visits in March." In May 1967 the Foundation gave Dr. Kenneth Clark, Black psychologist and former head of all Harlem poverty programs, $500,000 to rehabilitate the Civil Rights leadership. In June 1967, after chairing several secret Civil Rights leadership meetings, Dr. Clark announced that all the top leaders would cooperate in calming ghetto unrest in Cleveland. "Underlying causes of unrest," Clark said, "are found in classic form in Cleveland."

On July 14, 1967, the Ford Foundation announced that it was giving $175,000 to the Cleveland chapter of CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) for organizing. This was on the surface amazing. CORE had been started in 1942 by a coalition of Euro-Amerikan radical pacifists, mostly religious, and a handful of Black followers. Of all the historic Civil Rights organizations it was most known for its dedication to pacifist civil disobedience and social integration. But by 1967 it had undergone drastic change. At the 1966 Convention CORE voted to embrace Black Power politics. Civil disobedience and settler leaders were tossed overboard. CORE's founding National Director, James Farmer, was replaced by the more militant-sounding Floyd McKissick from North Carolina. Special Ford Foundation training programs prepared new "nationalist" CORE leaders such as Roy Innis (the very first trainee). It was noteworthy when the Ford Foundation began lavishly funding a supposedly Black militant group. A Cleveland CORE leader said: "Our job as an organization is to prepare people to make a decision on revolution or not. The choice is whether to take land and resources and redistribute them."

Cleveland CORE used the money to organize and pay New Afrikan youth for a Summer voter registration drive, and for setting up a voter mobilization drive for the November 1967 city elections. Ford Foundation funds paid for Cleveland CORE to set up rallies for the Black candidate for Mayor, Carl Stokes. And in the elections, Stokes became the first New Afrikan mayor of a major U.S. city (in the 20th Century). While both rebellions and savage police repression took place in 1968, Stokes' election was the rallies for the Black candidate for Mayor, Carl Stokes. And in the elections, Stokes became the first New Afrikan mayor of a major U.S. city (in the 20th Century). Stokes’ election was the beginning of a new pacification maneuver. Cleveland CORE hailed this election as a Black Power victory. A Ford Foundation representative praised the redirecting of mass energy into elections “as a flowering of what Black Power could be.”(22)

Foundation President McGeorge Bundy came out for independent Black community school boards, which was one of Stokeley Carmichael’s main Black Power demands in 1966. Co-opted Black Power had become a golden alliance between the colonial petty-bourgeoisie and the Empire’s ruling class. Just as the early, militant, direct-confrontation Southern student movement had been increasingly sidetracked into voter registration and bourgeois elections in the early ‘60s, the Northern New Afrikan rebellions were in part pacified by the same tactic put over under the nationalist-sounding cover of co-opted Black Power.

The manipulation of the Black Power Movement by the C.I.A., using many different covers, was made public policy by the Nixon Administration. All three present and past National Directors of CORE, for example, were personally brought up: James Farmer, who had always claimed to be a pacifist-socialist, became a sub-Cabinet official in the Nixon Administration; Floyd McKissick became a loud Government supporter in return for the promise of millions of dollars in Federal loans for his ambitious “Soul City” housing development; Roy Innis made CORE an organization for hire, unashamed at working for the C.I.A., the Zionists, the South Afrikan Boers and may other reactionaries willing to pay for a Black Power endorsement. President Nixon personally pushed the neo-colonialized concept of Black Power, saying in his historic national broadcast on April 25, 1968:

“For too long white America has sought to buy off the Negro—and to buy off its own sense of guilt—with ever more programs of welfare, of public housing, of payments to the poor, but not for anything except keeping out of sight... much of the Black militant talk these days is actually in terms closer to the doctrines of free enterprise than to those of the welfarist thirties—not as supplicants, but as owners, as entrepreneurs—to have... a piece of the action.

“And this is precisely what the Federal central target of the new approach ought to be. It ought to be oriented toward more Black ownership, for from this can flow the rest—Black pride, Black jobs, Black opportunity and yes, Black power...”(23)

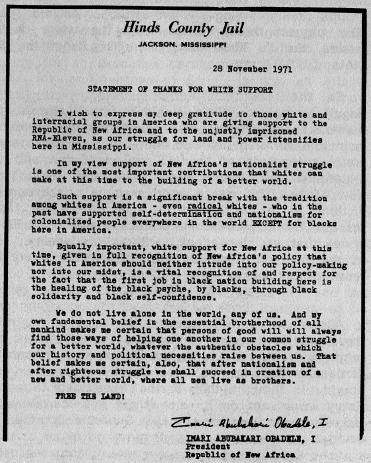

When Republic of New Afrika—Provisional Government Co-President Imari Abubakari Obadele was finally released from Federal prison during the 1970s. As President of the PG-RNA, Imari had led the move to establish a nation-building center in Mississippi and Louisiana. This move was crushed by U.S. counter-insurgency, ending in the August 1971 FBI-COINTELPRO raids in Jackson, Mississippi. Like other P.O.W.s, Imari noted the changes that the defeats had made in the Nation’s life. Most shocking in his eyes was seeing young women with processed hair—and finding out that this was because so many boyfriends were demanding it of them. To Imari it seemed as though they were in ignorance putting symbolic slave chains back on themselves.(24) These cultural regressions are not disconnected from the pseudo-nationalist, “cultural nationalism” of co-opted Black Power, which had a tremendous effect in the late ‘60s and 1970s on the daily lives of millions.

The Black Power Movement spoke in angry, militant-sounding language amplified by the imperialist media; it absorbed the energies of many honest and self-sacrificing New Afrikans. But like every political movement that assumes capitalist social relations and capitalist economic production, its inner cultural content was not about liberation but about enslavement. To note that the Black Power Movement was explicitly anti-Communist is just one part of it. Black Power explicitly preached the inferior position of New Afrikan women to New Afrikan men, for example. On the grounds that the kind of male-chauvinist, patriarchal nuclear family advocated by Carmichael, Karenga, and other (Daniel Patrick Moynihan) was somehow authentically “African revolutionary” or “communist”--while it was actually only their slavish imitation of the European capitalist family. Carmichael swaggered around saying: “The only position for women in SNCC is prone!” Ron Karenga said: “What makes a woman appealing is femininity, but she can’t be feminine without being submissive.” “Black Power” as capitalistic “Super-Fly”. And so the popularization of so-called Black Power only helped put the mental chains of slavishness and cultural regression back on folks.

The persistent effects of the co-opted Black Power counter-insurgency strategy can be seen in the lingering belief that electing Black politicians is a step toward freedom. In particular, the election of Black mayors is seen as the same thing as New Afrikan control of their nation. Not only bourgeois politicians, but “nationalists”, militant reverends, and the settler Left regularly turn out to tell the New Afrikan Nation this lie.

There are three things we have to understand about this. The first is that Black bourgeois politicians have no power at all. Richard Hatcher of Gary, clearly the most progressive of the Black mayors, said: “There is much talk about Black control of the ghetto. What does that mean? I am mayor of a city of roughly 90,000 Black people, but we do not control the possibilities of jobs for them, of money for their schools, or state-funded social services... Will the poor in Gary’s worst slums be helped because the pawn-shop owner is Black, not white?”(25)

The second thing is to see Black Power’s vision of community control for what it is. Since there is no way, under imperialism, for New Afrikan people to communally control the established institutions that determine their lives, to speak of “Black control” without socialism and national liberation only means the promotion of Black petty-bourgeois into supposed positions of institutional authority. That is why so much activity centers around electing Black mayors, having Black police commanders, Black school officials, Black corporate managers, Black office supervisors, Black professors, and so on. In other words, co-opted Black Power involved no power at all for the New Afrikan grass-roots, but meant plenty of promotions and new opportunities for the neo-colonial petty-bourgeoisie.

And lastly, we should see that the neo-colonial city ghetto is a puppet state. Co-opted Black Power was the C.I.A.’s forerunner for the less successful South Afrikan “bantu-stans” or “tribal homelands”. As we know, the settler-colonial regime of “South Africa” has set up within it little Afrikan pseudo-states. These fraudulent, dummy tribal governments placed in barren areas are used to pretend that the settler regime respects the democratic rights of Afrikans. Each of these little tribal pseudo-states is complete with an Afrikan “President” and “Cabinet”, Afrikan officials, flag and a little police force in snappy uniform. The “tribal homeland” has no real Land, no economic base, no independent relation to the world, no practical power or real sovereignty. But it has highly-paid Afrikan officials. Mayor Kenneth Gibson would be right at home there. Newark is a “tribal homeland” or “bantu-stan”, if you understand the dialectical relationship between Black Power “democracy” and Indian reservations and “South African” apartheid.

FALSE INTERNATIONALISM AND REVOLUTIONARY SET-BACKS

The repression of the first wave of New Afrikan revolutionaries seemed but a momentary set-back at the time. Robert Williams and the Monroe Movement in the 1950s, RAM and Malcolm’s Organization of Afro-American Unity in the 1960s started a revolutionary movement which promised to become even stronger. The late 1960s were a tumultuous time when the whole world was on the move pushing imperialism back. In Vietnam the stakes kept getting higher, U.S. casualties kept growing, while the liberation army was kicking ass. Che had left his cabinet minister’s office in Havana and became a guerrilla again. Peoples War was starting all over Afrika. And in China the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was rising against capitalist road bureaucracy within socialism. It was a revolutionary high-tide in the world. A heady time. Revolution here seemed to be not only likely but inevitable—and soon, too.

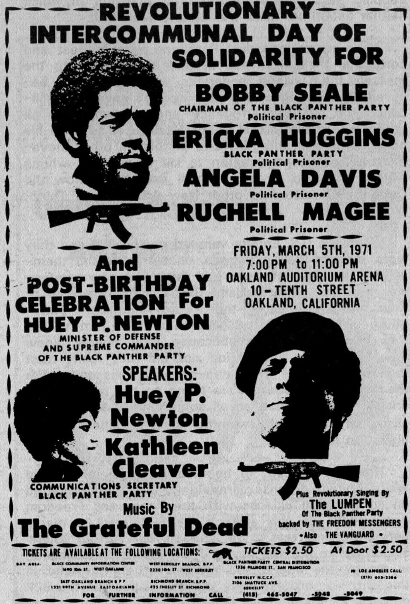

A second wave of New Afrikan revolutionary organizations came right on the heels of the first. These were sons and daughters of urban rebellions, part of the grass-roots trend of Black Power. The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1969, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers also in 1969, the Afrikan Liberation Support Committee and other new groupings quickly gained a mass following. New revolutionary organizations and bold new tactics grew side-by-side with the neo-colonial trend, challenging it for hegemony over Black Power.

The subsequent victory of the neo-colonial petty-bourgeoisie in co-opting the Black Power Movement was therefore not a simple thing. It involved certain imperialist-sponsored activities and propaganda. It also involved clearing the revolutionary alternative away with repression. Like the first wave of New Afrikan revolutionary organizations, the second wave was also unable to survive combat with the political police. The national revolutionary movement had severe internal contradictions, was incompletely developed, and was not able to seize the political leadership of the Nation away from the neo-colonial petty-bourgeoisie.

We need to apply dialectical and historical materialism to the development of the armed struggle beginning in the 1960s. Dialectics holds that all things develop through the working out of their own internal contradictions, not through conspiratorial maneuvering of outside forces. The beginning of modern New Afrikan armed struggle met defeat. Not because of FBI-COINTELPRO or the Klan, but because its own confusion over class and national goals and their relationship to armed struggle left it unable to combat the political police.

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in 1966, becomes for us a window to see deep into some of these contradictions within the armed struggle. While the BPP for Self-Defense was not necessarily the largest or the most advanced of the New Afrikan revolutionary organizations exploring armed struggle, it was certainly the most public. The Party self-consciously projected itself into the public eye, and its collision course with police gunfire made its development a matter of public record.

Armed struggle, as the highest form of struggle, inescapably imposes the need for the clearest political consciousness while at the same time being the necessary condition for such advanced consciousness. The Party was from its birth in 1966 an armed formation, in which every member was committed to fight the oppressor and if need be die in combat. Many, many ‘rads did die, and still today the kamps of Babylon hold former Panthers as well as other revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s. Of revolutionary audacity and courage the membership of the Party lacked nothing. But this Party came together at a time when political consciousness was young, raw and undeveloped, and when necessarily petty-bourgeois/lumpen class views dominated. For that matter, the BPP explicitly based itself on the lumpenproletariat, and tried to advance using petty-bourgeois/lumpen military concepts.

The Black Panther Party’s political-military strategy had come under considerable criticism at the time from forces within the revolutionary nationalist movement, who unfavorably contrasted it to Peoples War. RAM criticized “Huey’s open display of guns, brandishing them into the police’s faces...” and the related BPP lack of underground structure or any long-term planning for mass organization. The RNA-PG said that “Black Panther pronouncements and actions CREATE pretexts for U.S. military actions, by the police...”(26) But there are no accidental strategies.

The BPP was born out of the nationalist movement on the West Coast. For some five years Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were part-time students at Oakland’s Merritt College, while increasingly taken up with political discussions, street corner nationalist rallies, activity in the New Afrikan college student organization at their school, and study of Fanon, Mao, and other political writers. For most of those years they had been members of a “cultural nationalist” organization, the Afro-American Association. Both, however, had grown disillusioned with it. Huey had gotten into a fight at a party, knifed a brother, and spent eight months in jail. Bobby had briefly related to RAM, but split under disputed circumstances. He says that he quit because RAM wasn’t into action. RAM leadership insisted that he was purged for drinking and misappropriating funds. In any case, by 1966 both Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were still part of the loose San Francisco Bay Area nationalist scene, and were looking for something new to do politically.(27)

In the Spring of 1966 Huey, Bobby, and another brother were strolling up Berkeley’s Telegraph Ave., the center of student recreation off the University of California-Berkeley campus. Telegraph Ave. was a crowded “hippy” street scene, sidewalks busy with vendors and hustlers. As they passed an outdoor cafe, Bobby impulsively decided to jump up on a chair and recite his latest poem to the white student crowd. Police showed up, Seale was dragged down, and both Newton and Seale ended up in jail for getting into a fistfight with the pigs. Huey decided that they had to form a revolutionary organization that stood up to the pigs. They named it the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.

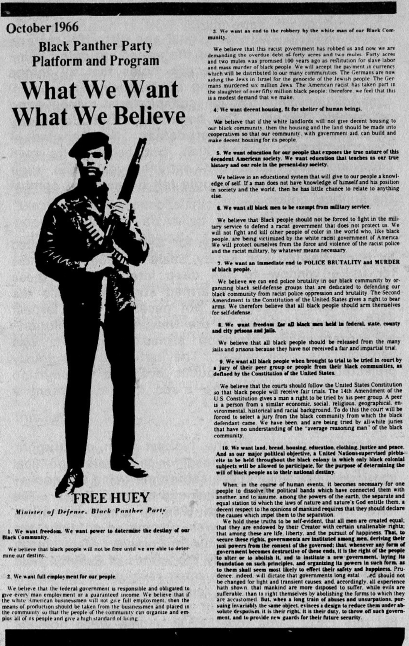

With the help of Huey’s brother Melvin, they drafted the Party’s ten-point program, that began with “1. We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black community.” and ends with “10. We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace. And as our major political objective, a United Nations-supervised plebiscite to be held throughout the Black colony in which only Black colonial projects will be allowed to participate, for the purpose of determining the will of Black people as to their national destiny.” The BPP ten-point program reflected the growing influence of revolutionary nationalism, of recognizing the distinction between the oppressor nation and the oppressed nation.

Their start is almost folklore now. Newton, a pre-law student, had carefully researched California’s legal code as it related to guns and the police. At that time the state law allowed people to carry loaded pistols, rifles and shotguns so long as they were not concealed. Newton and some others decided that this loophole in the law could be exploited. The first task was getting weapons. One day they were reading the newspaper about how the famous “little red book”, Quotations From Chairman Mao Tse-tung, had just been published in English. Huey got an idea. They went across the Bay to China Books, where the “little red book” had just gone on sale, bought a bunch, and drove back to Berkeley. Within an hour, hawking the “little red book” at the gate to the University of California campus, they sold all the books they had. With that money they drove back to China Books, bought the store’s whole stock of “little red books”, and sold them all to curious Berkeley students. They made enough money to buy two shotguns.

By that Fall of 1966 the BPP had recruited its first members, mostly from Huey’s neighborhood in Oakland, and had set up a storefront office. It says something about the popular mood that folks could be recruited to join a tiny political group whose members had to publicly face off with the police, while carrying guns. In public face-offs, Panthers refused to hand over their guns to the pigs, insisted loudly that “if you shoot at me, or if you try to take this gun, I’m going to shoot back,” and all the while lecturing the gathering New Afrikan crowd about their rights. The first time that happened, in front of the BPP’s Grove St. storefront office, a dozen men who had been watching immediately joined up.

In the next year the Party became a presence on the New Afrikan political scene. Not only was it growing rapidly but its aggressive armed stance had electrified folks. In April 1967 the BPP was asked by the family of Denzil Dowell, a 22 year-old youth who although unarmed had been shot six times in cold blood by Richmond police, to help them investigate the killing. Panthers interviewed witnesses and proved that the official police account was a fabrication. Guarded by twenty armed Panthers, Newton and Seale spoke to the street rally of 150 persons in the Dowell family’s Richmond neighborhood. Panthers accompanied the family and other New Afrikan residents to meet with the County Sheriff and District Attorney. Three hundred New Afrikans, some as young as twelve years old, applied to join the BPP that month in Richmond.

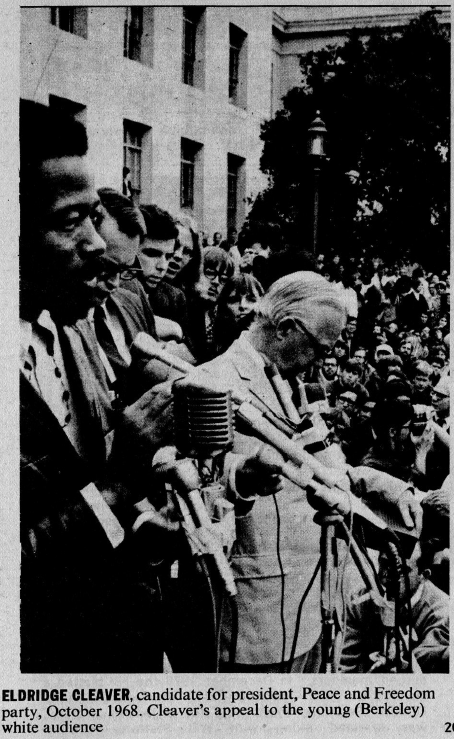

Another person who had joined the Party in early 1967 was Eldridge Cleaver, fresh out of Soledad Prison. Cleaver had become the New Left’s most promoted prisoner-writer, an object of settler “radical chic”. Already he was the Black staff member for the glossy New Left magazine Ramparts. Eldridge was a lumpen super-star. In February 1968 his book about himself, Soul on Ice, was published to rave reviews in the bourgeois media. Within weeks it was on the top ten best-sellers list. His entry into the Party leadership gave them a celebrity who was a brilliant propagandist. New Afrikans who had never heard of Robert Williams or Ella Collins were given Eldridge as the theoretician of Revolution.

By 1966 new Party chapters were springing up from coast to coast. In grammar schools New Afrikan children would sport black berets and play at being Panthers. There were many chapters in California: Oakland-Berkeley, San Francisco, Richmond, East Palo Alto, Los Angeles, San Diego, Sacramento. Speaking tours by Bobby Seale and Eldridge had set up new chapters in Chicago, Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia, and other major cities. In January 1969 the BPP was claiming 45 chapters, although some of these were just on paper. Members came from all classes: from the street force and from the children of the “Black Bourgeoisie”, from SNCC and from the U.S. Army, from factory laborers and college intellectuals. Internal FBI studies concluded that 43% of New Afrikans under the age of 21 “had great respect for the BPP”.

Many ‘rads were drawn to the Party because they were searching for advanced ideas. Bourgeois accounts of the BPP stress the drama of its gun display, while downplaying the fact that it was a political party. As a revolutionary party the BPP emerged as harsh, no-fooling-around critics of both bourgeois nationalism (“Green Power”) and the “cultural nationalism” trend. They said that people who went around in dashikis, who gave themselves Afrikan names and who sprinkled Swahili words in their vocabulary, but who refused to pick up the gun against the oppressor, were “buffoons” and “pork chop nationalists”. The party formally pointed out that nationalism was not itself a social program, and that only socialism could liberate the oppressed. These words had weight coming from a party which was talking about land and a popular vote to decide New Afrikans’ “national destiny”.

However, these advanced-sounding words expressed but a part of the Party’s reality. The two-line struggle is an expression of fundamental contradictions. As such it is present in all spheres of life, within all political phenomena. So the two-line struggle was not just between the old Civil Rights Movement and the revolutionary nationalism of Williams and Malcolm, for instance. It was also within the Civil Rights Movement, as we saw when the militant wing of the non-violent movement, led by SNCC, broke with the old concepts of integration and became more nationalistic. The two-line struggle continued within that as well. We saw how the move for Black Power, which was at first primarily a more grass-roots and nationalist trend, contained within it is own opposite—i.e. a disguised form of neo-colonialism.

The Oakland BPP leadership was in reality much less advanced than Malcolm and Williams. In significant ways they were less advanced than RAM. What sounded advanced was in part borrowed rhetoric. The BPP for Self-Defense was influenced by the petty-bourgeois student “counter-culture” of the San Francisco Bay Area. Just like their settler counterparts, Huey and Bobby were putting on an instant political line by borrowing rhetoric from the Chinese Red Army, from Mao, from Malcolm, from RAM, and so on.